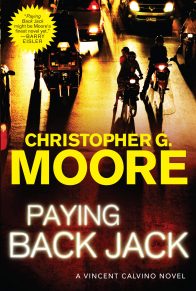

Three days into the Year of the Monkey, around midnight, Calvino perched on a stool at the Yellow Parrot jazz bar. He was killing time. Pratt, his police colonel friend, was running more than an hour late. The private investigator instinct made Calvino ask himself some questions. Then he stopped. Bangkok was Pratt’s town, his beat; he was running a little late, that was all there was to it. Calvino’s attention drifted until it focused on a twenty-something Thai waitress who pulled all male eyes within a twenty-yard perimeter. She glided like a bee, dancing from bottle to bottle, pouring drinks. She was packaged in a pink silk dress wrapped like mist around the waist and hips. It was the kind of dress that wore a woman. Her earlobes and throat were fitted with gold pieces; more gold bracelets encircled her wrists. The gold was a statement that she had successfully mined the Bangkok night for her precious metals.

She emptied the last shot from a Chivas Regal bottle as a Thai man in a business suit held a mobile phone to his ear and smoked a cigarette.

The waitress waited for some reaction from her customer. She leaned over the bar, smiled at Calvino, and then turned back to the customer.

“Hum hiaw,” she said, using a Lao expression, which immediately suggested she had sprung from peasant stock in the northeast. The Japanese businessman on the mobile phone laughed, and then washed away his smile with his drink.

Hum hiaw—the condition of a penis that even though suitably stimulated remains placid—was an emotional stinger aimed to puncture the male ego. She scored a bull’s-eye. The customer winced as his ego recoiled into an outburst of nervous, hollow laughter. Then he ran a finger along the edge of the gold bracelet on her left wrist, touching a three-inch scar.

He shook his head. “Hum khaeng,” he whispered. He was hard, he was telling her. But she grinned as if she wasn’t buying it.

“Hum hiaw,” she insisted, then pulled her hand away and swept to the other end of a bar, where another customer was holding up an empty glass.

When a Thai woman stared you in the eye and said, “Hum hiaw,” she was passing on a piece of confidential information, some personal intelligence. She had disclosed that she was from the region of Isan and that Lao (as opposed to Thai) was her native language—a Thai from Bangkok would have said, “juu hiaw.” And a woman in a Brooklyn bar would have said, “Can’t get it up. Can’t get it to stay up.”

In the Thai language, this was said as a joke to foreigners. Pood len. Talking fun. Most of the time Thais liked to play with language; it was fun.

“You’d never say that to a Thai boyfriend,” Calvino said to her. “He’d box you.”

The smile disappeared from her lips and she turned from the Japanese customer. “Farang know too much, not good.” She’d suddenly lost her sense of fun. Reminding her there were two sets of rules: one for the locals and one of the foreigners wasn’t appreciated. Her Japanese customer bought her another drink, and she drifted back into conversation with him, making a point to ignore Calvino.

Calvino knew that most jokes, even in Thailand, were like a fingernail rubbing a tender spot of despair or fear. Inside this world the hard were favored. Bangkok allowed them to show their stuff—to score, flash money, buy affection and respect; to accumulate followers who looked to them for protection. In these ways, Bangkok was no better or worse than Brooklyn. The same nocturnal raids, the same get-ahead and stay-ahead paranoia, the same strong arms and big swinging dicks building an empire out of force. He glanced at his watch again, then over at the large crowd by the door. There was no sign of Pratt’s shrewd eyes sweeping the room, looking for Calvino at the bar.

Overhead a string of dozens of yellowing New Year cards fluttered. Hum hiaw, thought Calvino. The cards flapped aimlessly and limply as the overhead fan blade rotated. Another Chinese New Year had come and gone. He liked the idea of a twelve-year cycle—everyone was some kind of animal, depending on the year they were born—a pig, horse, rabbit, snake, dragon, and several others. This year brought another animal—the monkey. If you were born in the Year of the Monkey—and if you believed human beings fell into one animal cage or another, as determined by the laws of this zodiacal zoo—then you bought the idea that a person born in the Year of the Monkey was clever, compassionate, and sex-mad. Monkeys weren’t Hum hiaw. People born in the Monkey Year were great lovers, always ready and willing.

Calvino sat forward and watched the waitress measure a shot from a bottle of Johnnie Walker Black, and he wondered what animal she was. Her Japanese customer with the mobile phone had gone. She drained the last drops into the last shot from the bottle; it had been a Chinese New Year bottle from Pratt. The odds were he had another two cycles of the monkey before he took the inevitable journey to that big jungle in the sky.

A slight shudder passed through Calvino as he watched the waitress, gift-wrapped and available on the installment plan Bangkok style, drop the dead bottle into the garbage. He arched an eyebrow as she looked up at him; and she arched one eyebrow in response. Monkey see, monkey do. One of the New Year cards broke free of its moorings and sailed in a rough tumbling action onto an ancient out-of-tune piano a few feet in front of Calvino. Several members of the Thai jazz combo—Dex’s Band—had wandered back from the break and the guitar player was warming up with a few riffs on an acoustic guitar. All night two white women in their mid-twenties had sat curled up like cats beside the piano. One of the women had a pair of large white thighs that rippled from her short hot-red skirt like paste from a tube stepped on by a jackboot. She reminded Calvino of Judy, his first cousin in Brooklyn. Judy had the habit of sitting with her skirt hiked up and other members of the family would notice and tell her she had nice legs. Judy believed she had nice legs too. But legs were like wine: They didn’t travel all that well from west to east. Some of the old hands had an expression for girls with Judy’s build—an elephant chicken. Every band attracted the groupies it deserves, thought Calvino, sipping his scotch.

Dex had been warming up on a tenor sax. He was one of Pratt’s arty friends who had taken on a hip Western name. Jazz and saxophones were the things Pratt and Dex shared. They talked about jazz like guys into sports talked about leagues, teams, and players. Dex and Pratt were players. For Pratt the sax was a serious hobby, but his job was a different world—he was a cop attached to the Crime Suppression Unit. Pratt had supported and encouraged Dex’s career, which was about to take off: He had signed a recording contract with a label out of New York. Pratt had been invited to the Yellow Parrot for a party after the bar officially closed. It was Dex’s last night as a local celebrity before heading into the big time of jazz in Japan and Europe. His first big tour. And Pratt had asked Calvino to drop in and say good-bye.

Only tonight, Pratt was running late and had missed the first session. On the break, Dex came over and leaned against the bar next to Calvino.

“Pratt says you got him involved in the pro-democracy movement, and now you’re ditching the masses to become famous. You would make a good American,” said Calvino.

Dex smiled. “Pratt says that, man?”

“Democracy will survive without you, Dex,” said Calvino.

“You’re forgetting we live in a country where people don’t always survive politics,” said Dex.

“Becoming famous is an insurance policy against getting yourself killed,” replied Calvino. Dex had received threatening phone calls telling him to stop supporting troublemakers. Pratt took the threats seriously, as did Calvino, who phoned a friend, an entertainment lawyer in L.A. named Tommy Loretti, and got Tommy to have Dex booked for his first international tour. Tommy put together five hotel engagements; that allowed Dex to leave Bangkok a hero instead of under the threat of armed attack. The people on the other side of the democracy movement had their own idea on how to handle troublemakers like Dex.

“I wanna thank you for helping, Vinny. Pratt said—”

“Pratt said I helped? Forget it. You gonna believe him when he can’t show up for your farewell performance?”

Calvino twisted in his chair and looked straight ahead, picking up Dex’s big, mournful eyes in the bar mirror. Dex had a large fleshy head; his hair was shaved except for a long Apache mane that divided his head into two lumpy spheres. “Stay cool, Dex. Playing jazz is an art form.”

“So is dying in your own bed when you’re an old man,” said Dex. He laughed and leaned in close to Calvino. “Pratt’s not gonna stand me up on my last night, is he?”

“What do you think, Dex?”

“No fucking way, man. Did I tell you some film people were in the other night asking if I was interested in a film role?”

“Japanese?”

“Americans,” said Dex. “Bad timing, I guess.”

“What goes around, comes around,” said Calvino.

“So they say. I’m still waiting for the ‘come’ part,” cracked Dex. Nice, thought Calvino.

A few minutes after Dex strapped on his tenor sax and began the second session, a cop in a brown spandex-like uniform, a hat with the plastic bill pushed back, a .45 riding high on his hip, made his way across the crowded room, seemingly toward Calvino, whose head was visible above the horseshoe-shaped bar. Dex’s last night brought in a standing-room-only audience, but the young officer had no trouble parting the sea of fans. Farangs and Thais crammed together over their drinks, craning their necks for a glimpse of Dex and his band. The officer pushed through a huddle of expat single white women: thirtyish, bored, indifferent, and distant, with diamond-hard faces set off by shark black dead eyes. The kind of eyes of someone who’d survived a head-on collision with life. It was as if the seal holding the soul inside had burnt out and the life force had leaked out, then boiled away into steam on the tropical heat of the night.

He watched the officer inch closer. Calvino felt the officer had been sent for him; and he wished it would take him an eternity to reach the bar with what could only be a piece of news he didn’t want to hear. Calvino ignored the officer for a moment and locked onto the faces across the floor. People with money and toys who had jaded out too soon. In Bangkok, to survive meant finding the right path to that final state. The worst cases were expats who had jaded out too soon; and a few had skidded off the road beyond jadedness. They filtered into the Yellow Parrot hoping that Dex’s tenor sax might revive them for a few hours, or for another night. The man threatened with death still came out to perform in public. He drew a kind of executioner’s crowd on his final night, thought Calvino.

The police officer squeezed in beside him as Calvino’s arm slowly lifted his drink. The cop watched him drink. As the empty glass was lowered, the cop slid a name card along the bar. Calvino glanced at it without exchanging a word. No word was necessary. It was one of Pratt’s cards. In engraved gold lettering, “Col. Prachai Chongwatana,” and below the name Pratt’s handwritten message: “Lt. Somboon will escort you through security.”

The waitress with the dance of the bee asked if Calvino wanted another drink. Calvino looked up from the card at the bartender and shook his head, and then lifted off his stool with a glance at Lieutenant. Somboon.

“We got far to go?” Calvino asked the young officer.

“Across Soi Sarasin.”

Was this some kind of a joke? Pratt had sent this guy to escort him across the road? Calvino looked hard at the cop, then decided to leave it, play it later. He let the cop sweep a path through the crowd. He winked as he caught Dex’s eye, his cheeks bulged as he blew hard into the sax. Dex lowered the sax and let the acoustic guitar player take over. He watched Calvino leaving the bar with the uniformed officer. There was something in the way that Calvino moved, a level of aggression, a swift, determined, hard stroke in his step. He had the look of a man trying to kick down a door before someone on the other side could hurt him. Dex had crazy ideas. It was his last night. People had threatened to shoot him. He closed his eyes, puffed his cheeks, and did what he knew best, played his sax.

A wind had broken holes in the gray ceiling of accumulated pollution, revealing the moon and stars. Taxis and tuk-tuks parked, let out and picked up passengers. The crowds spilled from sidewalk tables, mingling in twos and threes into the street. Opposite the bars was Lumpini Park. Some said Lumpini Park was the lung of Bangkok. Others said it was more like a lung in an emphysema patient. At the side gate to the park, two uniformed Lumpini district station cops stood guard and saluted as the police lieutenant escorted Calvino through an outdoor restaurant. The place called Mom’s restaurant was closed, and as his police escort led the way through the dark, narrow lanes of tables, Calvino thought about the author of The Man with the Golden Arm, Nelson Algren. He liked Algren’s three principles for living: Never eat in a restaurant named Mom’s, never play cards with a man named Doc, and never sleep with a woman whose troubles are greater than your own. Calvino prided himself on never having played cards with a man named Doc.

A ground fog swirled at ankle level above the concrete patio. Plastic chairs stacked upside down on the tables threw ghostly, elongated shadows. A moment later, they came out of Mom’s and onto a paved road. Twenty meters beyond the shoulder of the paved road, a paddle-boat churned through the water. A spotlight swept the shore and stopped on Calvino, who kept on walking toward the light. The splashing stopped as the boat docked against a wooden wharf, where dozens of plastic hulled boats were tied alongside one another.

“I have the farang,” said Lieutenant Somboon to the two officers in the paddleboat.

They said nothing, as they shone the light into Calvino’s face. He had put on the sunglasses that made him look like a blind man. One officer spoke into the walkie-talkie, and a couple of minutes later they had turned their boat around and pulled away toward the center of the lake.

“Maybe you should take off your sunglasses before you get in the boat. You might step wrong. Then we have two bodies,” said Lieutenant Somboon, stepping into the lime green boat with number 34 painted on the side. It rocked to one side, splashing water.

“Whose body you got out there?” asked Calvino, folding away his sunglasses and looking at the lake.

“Ask the colonel.”

“I will. But now I’m asking you,” said Calvino.

“Get in. We go now,” Lieutenant Somboon said, ignoring the question.

“An old Patpong line,” said Calvino. The joke didn’t dislodge the look of distrust on the lieutenant’s face. Being assigned to escort him from the Yellow Parrot to a murder scene must have been costing Lieutenant Somboon a load of face, thought Calvino.

Calvino eased off the wharf in the dark, touching a foot into the molded seat cubicle next to the one occupied by the lieutenant. He hated the look of a dead body submerged underwater—it often looked like a French fry pulled out of a Coke bottle. He sat crumpled up, wishing he were back on dry land, listening to Dex’s sax. The Chinese New Year moon had a small slice missing, as if an axe had shaved it. The pinkish fog rolled out from the empty outdoor restaurant, following Calvino across the lake. The boat moved out as they worked the bicycle pedals on the floor of the boat. Soon the wharf disappeared as moonlight rippled across the lake, leaving the shore in darkness. As they paddled closer to the center of the lake, a number of boats were circling around a common point. He could hear officers speaking Thai and directing spotlights at an empty boat. As they pulled up, one spotlight swung around and illuminated the paddleboat. An officer in Pratt’s boat reached out bare-handed and steered Calvino’s boat alongside.

“Why is it I think you wanna spoil my evening?” asked Calvino.

He followed Pratt’s eye line to the left, where a large black tarpaulin covered the form of another of the toylike plastic boats. He stared at the tarp, thinking about Calvino’s law: People were divided into two groups—those who sought protection and those promised protection. Tarpaulins were invented to cover the bodies of those whose protectors had let them down. He watched as the tarp was pulled back to reveal the identity of the body.

“Whatcha got, Pratt?”

With a pole, Pratt peeled the tarpaulin back from over the face as water ran off the sides.

“A dead farang. Jerry Hutton. An American. Twenty-eight years old. The kid you helped a few days ago.”

“Shit, Pratt. I should have gone with him. Christ, I had this feeling something was wrong.”

Calvino, feeling sick, leaned over the victim’s boat. It was Hutton. Maybe five-eight, stocky, a moon-faced kid with a receding hairline. He could have passed for forty with his gut. Hutton was from Scranton, Pennsylvania. His old man had worked in one of the steel mills when America still made steel—until he was hurt on the job and went on permanent disability. His parents were divorced, his mother an alcoholic. Hutton decided working in the mill wasn’t for him. He went to community college and became a mass communications major. Then he found there were as many mass communications majors as ex-car plant workers. But Hutton never gave up his dream of becoming involved in show business. He became a freelance cameraman, working off and on—mostly off—in Chicago. Then left for Thailand. He hustled a few TV news assignments for the Europeans. Enough to break even in a slum. Hutton lived in a two-room slum with an ex-Soi Cowboy bar ying named Kwang and assorted members of Kwang’s upcountry family in a complex of sweatshop shacks hammered together from stolen condo site lumber. The slum was next to Calvino’s apartment. They were neighbors. Co-slum dwellers on a backwater soi that flooded every rainy season, driving the snakes from the sewers and the rats to the high ground. He had lasted three years in Thailand before being fished out of the water in the lung of Bangkok.

Calvino stared down at the body. “And you thought Vinny might have an idea how his neighbor ended up dead in Lumpini Park Lake.”

“Something like that,” said Pratt. “It is the same guy?”

Calvino nodded. “One and the same.” He turned and looked straight at Pratt. “You’re thinking that just maybe that Chinese guy on Sukhumvit whacked him. Forget it. Not a chance.”

Colonel Pratt smiled. “Khun Sompol threatened to kill him. He lost a lot of face in the accident.”

“Chinese don’t kill you for running over a couple of cooked ducks and spilling their rice.”

Colonel Pratt looked away, sighed, shaking his head. Who knew why anyone goes about killing another person. The papers always classified a murder as either a business or a personal conflict. A clean, uncomplicated vision of why people murdered others. Some of the time, the vision didn’t fit. Like with Hutton, thought Pratt.

Calvino reached down to close Hutton’s eyes; they had gone dead-battery flat, and the image of the women at the bar listening to jazz flashed through his mind. He caught a glimpse of some pressure marks on Hutton’s neck. When Calvino rose again, Pratt held out a necklace of small wooden penises with water dripping from the tips.

“What do we have here?” Calvino said, taking the necklace. He turned, held it against the light, then recognized it.

“Amulets,” whispered Colonel Pratt, as the scratchy sound of walkie-talkies broke the silence.

“Upcountry Thais wear them. Rice farmers from Isan,” said Calvino.

“But not farang,” said Colonel Pratt. “Or am I wrong?”

“It’s either a fashion statement or an attempt to keep your dick from going limp. Or in this case, a murder weapon.”

“Was he depressed? Could he have drowned himself? Maybe it was an accidental drowning. A boating accident. We don’t know he was killed.”

“Look at the marks on the neck.”

“He hooked himself on the boat. The marks are from the necklace. He tried to surface and couldn’t.”

“He was going to a meeting on a film,” said Calvino. “He was excited. This was gonna be his big break. His dream come true. He wasn’t depressed or worrying about his dick.”

Calvino twisted one of the wooden penises over on his palm. He guessed the length as no more than two inches, with a circumference of about an inch. Seven anatomically accurate cherrywood penises, each indicating a skilled craftsman’s perfect knowledge of wood, not to mention a surgeon’s skill in circumcision. At the base of each wooden penis a hole had been drilled and a tough piece of water buffalo hide threaded through it. A black-headed nail had been hammered into the tip and protruded like the lidless eye of a bug. Calvino cupped his hand around three or four of the amulets and shook them; the penises rattled like a snake ready to strike. Encased inside the hollow penises, a tiny lead pellet was sealed.

“He had one of those women who used Hum hiaw every third sentence,” explained Calvino. “A ballbuster ex-bargirl type.”

Colonel Pratt smiled as Calvino lowered the necklace into his hand. “What about this business meeting?”

“The film was about this kind of superstition.”

“You have a name?” asked Colonel Pratt.

“He was closemouthed about it.”

Pratt rattled the amulet and dropped it into a transparent evidence bag.

The amulets connected the believer who wore them to the supernatural. It was another kind of protection system for people short on faith in their human protectors. Amulets granted access to the invisible forces, the ones from the spirit world that kept cocks hard, people safe from evil, accidents, enemies, and the hungry ghosts in check. A wooden cock was a sacred thing, a supernatural phone system allowing dialogue to be carried on between the spirits and humans; only Hutton had found the line engaged when he needed to make the call.

Pratt had been right about the marks on his neck. Maybe he had drowned himself by hooking himself under the boat. But Calvino knew the kid and didn’t buy the theory for a moment. To him it looked as if in a world haunted by a life-and-death struggle, Hutton had been a loser; in a world where no one ever survived for long, Hutton had spent his last moments on earth in Lumpini Park, fighting to breathe, as someone held him under, marking the time and watching the bubbles grow thinner and finally the water still as the breathing stopped and the pinkish fog and Chinese New Year moon cast a last anguished flicker on a surface as clean and still as glass.