“All we really have to do is die. What matters at the end of the day is were you sweet, were you kind, did the work get done.”

The screen shouts.

Beeeee afraid! Low types of people are everywhere; in cities, in towns, in your backyard! In other countries. Drugged, crazed, mindless evil is at large!

Out in the world, Mickey Gammon remembers his last day of school a few weeks ago. Mickey speaks.

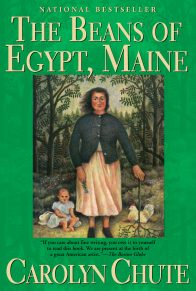

Last March, my mother wanted to come back to Maine. My brother Donnie came and got us and he had gotten fat, but I recognized him. (Ha-Ha!) Okay, just a little fat. A gut.

We rode back in the night. To Maine.

The school here in Maine is a joke.

Like the other school was a joke. In Mass. You were supposed to keep your locker locked to keep people out, but there was a rule they could search your locker on demand. There’s two types of teachers wherever you go. The kind with slitted eyes that try to get you to fight. And the ones, mostly women, who talk to you like if they say the right thing, they can change your life, that there is something wrong with your life. I say fuckem, there’s nothing wrong with my life. That was the same thing back in Mass. It’s like they either want to kick your ass or sniff it.

My brother’s wife is sweet. She has everything: looks, brains, composure. And I especially like her T-shirt with the Persian cat printed on it . . . something about the idea of that cat’s face goes with her face . . . the big eyes. Meanwhile, she has arms like Wonder Woman, like she could wrastle you down if it got to that. But she’s not one of them man-women you see around. Erika is soft like a pillow. My brother Donnie ever lays a finger on her, I’ll break his face.

Meanwhile, I was just taking the bus to school, to finish out the year at this school here. I don’t mess with their books—you know, frig with them, write shit in them, or vandalize things. That’s stupid. But I figured before the last day in June I was going to draw a picture of Mr. Carney sucking a pony’s cock on a separate piece of paper. And, you know, tape it into the book.

Okay, so my life isn’t perfect. You wanna hear this? I got a little nephew . . . Erika and Donnie’s kid, name’s Jesse. He’s got a weird cancer. At first it was slow, but now it’s fast. Imagine! A little kid like that. He don’t even talk anymore.

So while I was in class one morning drawing some doodles on my paper, listening to them all whine about South American exports and the Incas or some such shit, the door opens and—yes, it’s the cops. They have a marijuana-sniffing dog and the teacher who is in on this like some fucking spy says that the dog is here to sniff our lockers, all the student cars, and, yes, us. She says the officer is just going to walk with the dog down between the rows, and unless the dog indicates illegal substances on us, none of us will be searched. “It’s just a routine thing,” she says. “We’re sure that no one here has any illegal substances on them.”

Wellllll, I was sweating in a cold way all over. I hadn’t had any weed on me for weeks, but I had this horror, suddenly, that that sucker was going to take an interest in me because of my thoughts.

So the Nazi-Pig comes along and his dog is going along . . . you know, like an ordinary dog . . . and he’s cleared two rows without finding what he likes, and as he is coming nearer to me I’m feeling freaked, and this kid Jared behind me, he says, “That dog sniffs my crotch, I’ll kick his face in.” He said this wicked soft, but Mrs. Linnett, with fucking amplified-radar-electronic ears that could probably hear your faucet dripping in another state, says, “What’s that, Jared?”

And so the dog has gone past me and Mrs. Linnett tells Jared to “Go to Mr. Carney’s office.” And she apologizes to the Nazi and makes a real scene over Jared.

At lunch, we heard that three kids were caught, one with a toothpicksized joint and two with a smell that meant they’d had the stuff on them recently. Everyone, the teachers and all the obedient Honor pansies and killer sheep were pale in the face, wondering how our school has got this terrible drug problem. Some were saying they just know there must be LSD too, and coke and heroin, crack and crank, OxyContin, and whatever, but dogs can’t sniff that yet. The whole cafeteria was in a kind of high squeally furor . . . loud . . . like panicked mice. I wasn’t hungry. I stabbed my fork into my apple. I said, “Fuck this Alcatraz!!” and I stood up without my tray and walked outta there. And in the hall, Mr. Runnells, one of them that guards the cafeteria doors, says, “And where do you think you’re going, Gammon?” And he reaches out like he’s going to put his hand on my arm. And for some reason beyond reason, I started to cry—the trembling mouth, the shaky voice, tears in the eyes. It’s like they got an electric paddle touching every part of you, making you do things against your will. The place has an ugly power over people.

I stepped away from him and said “Bye now” in a kind of nice way and went past Mr. Carney’s office and out the glass doors and out into the sun, and then I started running like hell.

Screen brays.

These flavorful burgers, these potato-flavored salt strips, these fizzy syrupy brown-flavored drinks in tall cups are waiting just for YOU. Go to it! NOW!

Out in the world.

Thousands of little red, gray, white, or blue cars and billowy plastic-bumpered sport trucks and SUVs snap on their directionals and whip into the asphalt passages of the drive-in order windows of any one of thousands of the identical burger stations.

Now, in summer, we see Mickey Gammon at home.

The walls of this old house have a weary cream and green wallpaper. Horses and carriages, men and women. Tall arched elms.

The shades here are drawn, shades yellowed with age. The light of this room is therefore dark but golden.

There’s a car chase scene on the TV. Vigorous and bouncy. But Mickey Gammon’s mother, Britta,* keeps the sound down because of the child, Jesse.

Jesse, almost age two, is shrinking. A thick-legged, noisy, gray-eyed boy whose favorite word was not no but why? Now shrinking. Stretched out on the couch. His skeletal legs seem awfully long.

Toys all around. Blue plastic car. Yellow plastic car. And a plastic-haired doll. Plastic: convenient, affordable, but terrible to the touch.

Mickey has just come in. Fifteen and free as a bird. He smells like somewhere different from here. Other homes. Other considerations. He kneels against the couch. His gray, always watchful, almost wolf-like eyes press like a hand over Jesse’s baseball print pajamas and the nearest small hand. Mickey speaks something low that his mother, Britta, over in her chair, cannot hear, but Jesse does. Jesse stares steadily through the magnificent pageant of his pain into the soft spoken word.

In this household, there is no money today. No money. No money. No money.

Out there in the world are whole bins of pain pills unreachable as clouds. The key to painlessness is money. Money is everything.

Mickey finds honor.

He is walking the long back road some call the Boundary. He is a light and fast walker, staying to the road’s high crown. Light and fast, yes, but also cautious and manly, a gait that is articulated at the knees. Such a fine-boned creature, this Mickey Gammon. Narrow shoulders. Little tufty streaky-blond ponytail. Dirty jeans, and hipless. Fairly androgynous at first glance. At first glance.

He can hear shots up ahead in the Dunham gravel pit. And then, beyond that, a deeper and darker aggression, a thunderstorm rumbling in from the southwest. When he gets closer to the opening of the pit, the silvery “popple” leaves are already starting to flutter, and upon his hot face the restless air is like a big God hand of airy benediction.

He sees four pickups, a newish little car, a pocked Blazer, and at least eight men, none he recognizes, yet he is under the good and nearly true belief that his brother Donnie knows everyone in Egypt who is near his, Donnie’s, own age and, yes, almost anyone might also be a distant relative.

Mickey walks his arrow-straight and light-step walk to where the group is standing with their firearms and thermos cups of coffee, and he sees one man squatted down with a .45 service pistol aimed at a black-and-white police target, a target with the silhouette of a man, only about fifty yards away on a wooden frame. Mickey slows his pace just before reaching this group. Guns? Mickey has no problem with guns. It is having to talk that brings him terror.

The man is rock steady in his aim, taking a lot of time. Silence before the pounding crack of a gun is always a momentous thing.

The other men turn and see Mickey. Some nod. Some don’t. None speak. One man is sitting on a tailgate, wearing earmuff-style ear protectors, his fingers nudging the double action of a revolver with soft sensuous clicks. The men who have acknowledged Mickey have turned away now to watch the framed target. One guy watches through a spotting scope on a tripod on his truck hood. The breeze rises up and gives everyone’s sleeves and hair a flutter. The sand moves a bit. And then there’s another rumble coming closer fast from the southwest.

Mickey moves lightly, stepping inside the edgy-feeling perimeter of the group, and sees, there across the tailgate of one truck, a Ruger 10/22, a Springfield M1-A, and several SKSes: three Russian with the star and red-yellow finish, a couple with fold-up vinyl stocks, black, light to carry, easy to hide. And a whole selection of full auto military-issue Colts. Two AR-15s. A Bushmaster. And two AK47s. Some of these are, yuh, the real thing. The thing made for war.

At last the shooter squeezes the trigger, and the deafening crack almost feels good to Mickey’s ears.

The guy with his eye to the spotting scope looks grim. “Seven!” he calls.

The shooter, dressed in dark-blue work clothes, no cap, bald but for horsey gray hair on the sides and thorns of gray hair on his tanned and lined neck, dips the .45, then raises it quickly, squeezes off four rapid shots in a row. Echoes among the hills multiply the four shots to a lively staccato. And then the supreme BOOOOMMM!; this the thunder of the storm marching closer.

Mickey spins his studded leather wristband, which is what he always does when he doesn’t know what else to do, watching the guy with the spotting scope, who now calls out, “Ten X! Ten! Two sevens!” And the shooter slips the .45 into its holster, which is against his ribs outside his shirt but is the kind you wear under a shirt if you plan to conceal it.

Mickey says croakily, “Anyone got a smoke I could borrow?”

There is a guy standing very close to Mickey who is of medium height, small-waisted, fit, wears a red T-shirt, jeans. Very square-shouldered. Black military boots and a soft olive-drab army cap, a very fancy black-faced watch, looks more like a compass. Maybe it is a compass. And sunglasses. Metal frames. Cop glasses. Like the Nazis wear to school when they bring in their drug dogs. But this guy has a mustache, the kind that crawls down along the jaws, a Mexican mustache. Arms are not thickly haired. Nothing hides the impatient pulsing musculature. He says, “What’s that you say?”

Mickey can’t exactly see this man’s eyes because of the sunglasses, but he can tell the guy is looking him up and down.

A hefty white-haired guy with a white sea-captain’s beard says, “Right here,” in a voice that is high and quavery for such a big guy. He steps toward Mickey with the pack, shakes two into Mickey’s hand, and says cheerily, “I’m not starting you on a bad habit, am I?”

Mickey replies without a smile. “I’ve been smokin’ for five years.”

“Breakin’ the law.” This voice is shaly and made for hard reckoning. Mickey doesn’t look to see which face owns it. It’s beyond the sunglasses guy so it is not the sunglasses guy.

Another voice, letting go with a small shriek of laughter. But no words. Also not the sunglasses guy.

“What? Artie break laws?” This, another voice, as tight as a stricture, and yet it means to be teasy. This voice beyond the first truck.

Many small chortles overlapping and flexing. Earthworms in a can overlap and flex too. Faceless laughter. Mickey keeps his eyes lowered.

Hot breeze blows some more sand around. Then the BOOOMMM! and matching flutter of light in the darkening southwest. Mickey now watches two really young guys, maybe not yet twenty, murmuring to a small, dark-haired, dark-eyed older guy with a mean-looking hunched bearing who is reassembling a black-vinyl-stock SKS. Even his ears have an inflexible, shiny, mean look to them.

A guy with a camouflage-print T-shirt, very thin, bony, urgent-looking guy, clean shave, freckles, almost no eyebrows, reddish hair, and a big smile, asks Mickey, “On foot today, huh?” He selects an SKS from the tailgate, pulling it away quite theatrically with both hands, raises his foot to rest on a plastic ammo case, then places the rifle across his thigh with stiff, animal, almost bewitching-to-see grace. Mickey eyes the flash suppressor on the end of the short carbine barrel, the long, dark, curved, extended magazine, says, “I have a ’sixty-six Mustang in Mass . . . everything but the body is real nice . . . sixty thou’ original . . . but needs some stuff . . . tires mostly. Couldn’t move it. Not roadworthy.”

“Lotta road between here and Mass,” declares the hefty sea-captain-beard guy with a cackle. This is the guy called Artie.

Mickey nods. Pokes a cigarette into the corner of his mouth. Snaps a match alive, cupping his hand and hunkering down to give the flame shelter from the wind; takes the first drag hungrily; drops the match into the sand.

“You walk from Mass?” another guy softly wonders, great, tall, rugged, clean-shaved guy in full camouflage, heavy-looking BDUs. Long sleeves. Looks hot.

Mickey replies, “No.”

The guy with the sunglasses and red T-shirt, thick dark mustache, has turned away, sort of dismissively, but he still hangs back, an ear on what’s being said.

The full-camo guy picks up a stapler and fresh target and trudges off toward the open pit area.

The sea-captain beard, hefty, high-voiced Artie, asks Mickey, “Do you shoot?”

Mickey says, “Yuh, some.”

The bony, urgent-looking, red-haired guy, not smiling now, advises, “If you keep your aim up, you’ll be glad some day.”

Mickey says, “I like shootin’ all right.”

The red T-shirt guy with the sprawling mustache, sunglasses, army cap, and awesome black-faced watch stares after the baldish guy, who is ripping his target from the fifty-yard frame.

Big guy with full camo trudges the long open pit to a frame against the bank at a hundred yards, the wind wrestling earnestly with his target as he staples it to the wood.

The red T-shirt guy now seems to be staring at Mickey, though with the sunglasses one can’t be absolutely positively sure.

Mickey smokes his cigarette down. He has pocketed the other. He now leans against a fender, feeling the thunder in the ground, watching the purple-black part of the sky flutter with big jabs of light, splitting open right over Horne Hill, the sweet breeze touching him all over, the tobacco smoke’s big satisfying work done inside him, the men trudging around him, and their voices, both grave and playful. Alas now, they speak of the storm and discuss whether to wait it out in their vehicles or leave.

The red T-shirt guy asks Mickey his name. Mickey tells him. He asks Mickey his age. Mickey says sixteen, which he is, almost. He asks him what kind of gun he has. Mickey says a Marlin .22 Magnum.

“Just one?”

Mickey says, “Yep.”

The guy asks, “Where do you live?”

“Sanborn Road.”

The bony, urgent, eyebrowless guy, overhearing, calls to him, “You live in that new place over there?”

“No, in the big one. I’m Donnie Locke’s brother. Been in Mass for a while. I’m livin’ here with him now.”

The full-camo guy is coming back through the wind and wild sand. Wind getting some real gumption now. Mickey can see through one side of the red T-shirt guy’s sunglasses, eyes that never seem to blink.

Now Mickey leans into the open door of the Blazer and casually sorts through shot-up police and circular competition targets. “You guys are good,” he says.

“Not really,” the red T-shirt guy says, rather quickly. “When your life is at stake, your first four shots are what counts. There’s no chances after that. You can’t have twenty shots to warm up.”

Mickey nods, picks something off the knee of his frazzled filthy jeans: a green bug with crippled wings. He scrunches it. With a murderous CRACK! and the sky dimming blue-black in all directions, light scribbles and splits into veins—and now rain. A few splats.

The red T-shirt guy seems to be looking at Mickey hard.

The tall full-camo guy just stands there looking straight up, eyes fluttering with the beginning rain, his big thick neck looking vulnerable and pale with so much of the rest of him covered. “Is this a break-up for home, Rex? Or should we wait it out in the vehicles?” His voice is soft, but he announces these words deliberately, words of consequence.

The red T-shirt black-mustache guy has pushed his cap forward, as if to hide his eyes, which, because of the sunglasses, never showed in the first place. “These storms aren’t usually more than . . . what, twenty minutes?”

And so they wait it out.

Rain comes hard. Smashes down on the truck’s cab, where Mickey sits with the red T-shirt guy. The guy has folded up his metal-frame glasses and placed them on the dash. He reminds Mickey of a raccoon, meticulous and wary. His eyes are pale gray-blue in dark lashes, and there’s settling and softening around them, which means he’s at least forty-five, maybe fifty. Not real friendly eyes. Nor is there rage in those eyes. His eyes simply take in but do not give back. And with the mustache filling in so much of his face, the eyes have significance. But no, his eyes don’t show much more of his humanity than his sunglasses did.

He has given Mickey a handful of folded flyers about emergencies and natural disasters and civil defense. There is a bold black-on-white seal on the front of the flyer, showing a mountain lion’s form silhouetted inside a crescent of lettering. The guy tells Mickey, “My number is there in case you are ever interested . . . also my address, Vaughan Hill. Come over sometime and bring a friend. You’re always welcome.” He indicates the truck parked on their left with a dip of his head. It’s only a hot grayish-green blur through the rain-streaked windows, but Mickey knows the big quiet full-camo guy is in that truck. “That’s John Stratham, my second-in-command. Another officer, not here today, is Del Rogers. He does a lot for us over in Androscoggin County—a unit that’s growing, maybe a little too fast. You’ll see him if you decide to come to meetings. He’s been real important to us in sniffing out some . . . uh, problems we had a few months back. He’s dedicated. A real patriot.” He places his right hand on the steering wheel, but he doesn’t play with the wheel like most would do. He says, “Some people don’t give their last names at meetings. That’s up to you. This is all in confidence. I will need to do a check on anyone who is seeking membership.”

Mickey looks down at the flyers in his hands. Mickey is very, very, very quiet. Mickey, whose pale eyes are just as unrevealing and steely as this man’s eyes are. The crescent of lettering around the mountain lion reads BORDER MOUNTAIN MILITIA.

On the back fold of the flyer: Richard York, Captain/Vaughan Hill Road/Box 350, RR2/Egypt, Maine 04047.

The guy explains that most people call him Rex.

The rain really pummels the hood and cab roof now, and the windshield looks like a thousand dark and silver wrinkles.

Mickey says nothing. His streaky blond ponytail is so thin and silky and without substance, it turns up a little to the right. Sweet. And now his unwashed smell is casually seeping through the humidity of the cab. This guy Rex smells like his T-shirt has had a real dousing of fabric softener. Mickey figures this is because there is a woman in Rex’s life. He glances at the hand that’s now kind of fisted on the left thigh of Rex’s jeans. Yes, a wedding band.

Outside, after the storm, the air is as heavy as a rubber tire. But it smells wonderful. Rex invites Mickey to shoot his own service pistol, which he pulls from behind the truck seat. “Never go anywhere without your Bible and your gun,” Rex says, at least three times. The tall soft-voiced second-in-command, John Stratham, gives Mickey some good pointers. For the first time, Mickey notices that John has an embroidered patch on the sleeve of his long-sleeved BDU shirt, the mountain lion and crescent of lettering, black on olive green: BORDER MOUNTAIN MILITIA. Striking to look at.

The target, like most of the others, is of a human shape and is placed at fifty yards for this particular gun. Mickey mostly misses the chest and head. In fact, he mostly misses the black targeted shape. From where they all stand, the spots of his hits show plainly and painfully against the white. He feels this is goofus, but these guys seem impressed. The hefty white-haired sea-captain guy, Artie, says “Good goin’!” and thunks Mickey’s shoulder. The hunched guy with the mean ears growls, “Got ’im runnin’.” The big quiet John nods. And Rex, with his sunglasses back on, says nothing, but his chin is up and he is feeling his dark, full, sprawling mustache carefully.

In a small American city in the Midwest.

A station wagon waits to make a left turn in snarling, fumy, carbon-poofing traffic. It exhibits a bumper sticker that reads MY CHILD IS A PLONTOOKI HIGH SCHOOL HONOR STUDENT.

From frozen Pluto, tiny microscopic Plutonian observatory observers observe the brown daytime spotting and pink nighttime hazing of what we have come to think of as life here on Earth. Tiny microscopic Plutonian officials speak.

wjox blup sssssooop ’G jrigip bot wjp st wjpt xt!

Six-and-a-half-year-old Jane Meserve speaks from a room at the St. Onge Settlement.

It is bad for my Mum. Someone help her! Someone with power. Help her! Help me! And my dog Cherish. Gone. Nobody tells me what happened.

Donnie Locke at home.

This old and loyal house! Belongs to Donnie Locke. No mortgage. Donnie Locke, Mickey Gammon’s half brother. It is home for Mickey and Britta too. Britta is the mother the two brothers have in common. Different fathers, same mother. Yes, Britta lives here too since she returned from Massachusetts, because Massachusetts didn’t work out.

Donnie Locke watches Mickey hard from his chair at the table. There’s a TV here in the kitchen. TV in the living room. Other TVs in other parts of the house. Not great TVs, but something to make do with. Both the kitchen TV and the one in the living room as seen through the two open doors of the little entry hall show a one-half-minute musical spectacle of the generic modern woman in the shower with water beading up on the skin of her shoulder, the ecstasy of huge teeth and violent water, America’s message, BE CLEAN, BUY DETERGENT BARS, and BODY SHAMPOOS, HAIR SHAMPOOS, DEODORANT POWDERS, and ANTIPERSPIRANTS that smell like SEA BREEZES. Cleanliness makes for opportunities.

Well, yes, Donnie Locke is clean. Fresh and perma-pressed, nothing to offend. Like obedience to God. Shouldn’t this guarantee you something? If not opportunities, at least forgiveness?

Donnie Locke isn’t looking at the TV. He watches his unwashed, cigarette-stinking, raggedly-dressed half brother Mickey, the fine yellow-streaked hair tied back into an inessential ponytail, the pale cold eyes that never meet Donnie’s eyes. It is easy to watch the boy, to stare ruthlessly at him. He doesn’t seem to mind.

Upstairs in this large old house, the younger kids make a racket. Donnie’s kids by his first marriage to Julie Nickerson, and then Britta’s youngest child, Celia, fathered by what didn’t work out in Massachusetts. And then there’s some neighbor kids. A regular shrieking, thumping, crashing mob.

Donnie Locke smiles a flicker of a smile, wrenched by a thousand emotions.

Mickey has just come in from being out somewhere doing something, probably messing with cars or snowmobiles with some of his loser buddies he met at school this spring. Tinkering. Something to climb into and under. Donnie was never much for that stuff. He made good grades in school, working hard at it, the family’s pride and joy. And his BA from Andover Business School. Yeah, he worked very hard at it, and he hated every minute. But what else was there? You have to get ahead. Or sink. This is what the guidance counselor said, and . . . well, everybody says it. And what else on this planet besides his ‘success’ could make his mother Britta’s heart sing?

The boy Mickey picks open the refrigerator door and gets out the plastic pitcher of red punch and pours a glassful and drinks it. Neither brother has a single remark. No Hi. No Hey. No Hot ’nuff for ya? Donnie is afraid to speak because he knows it will come out resentful. He wants a happy home, like when he was very young. His quiet mother and aunts. His earnest father and Gramp. Hopes and dreams measured by seasons. That’s all he wants now. Happy home. Simple life. Hopes and dreams. Yes, that would make his heart sing.

This man, Donnie Locke. Mid-thirties. Somewhat bald. But a great big blond, walrus mustache. Short sleeve beige-pinstripes-on-white shirt. Trim trousers. The generic man. The job requires this, his job at the Chain.

Donnie Locke’s father, not Mickey’s father, “Drove truck,” made okay money. Was one of the many Lockes and Mayberrys who have owned this house, its various farm buildings, and its land—field, woods, and stream—for a half-dozen hard-headed hard-hearted generations, all those Lockes and Mayberrys gone now, and their crumbling tools and outmoded thinking and outmoded dignity and laughable hopes and dreams, gone now to the Land of Death. More Lockes and Mayberrys there in the Land of Death than here in the Land of Life.

Here in this life in the brand-new century is Donnie Locke, with the pink unused-looking hands and chain-store name tag and after-work pink TV light in his eyes. Still living in the old Locke-Mayberry place, the thing that makes him Donald Locke. Because nothing else in this world makes him be Donald Locke. Yeah, “one of the Lockes.” Yes, here he is.

Nearby, at the St. Onge Settlement, six-and-a-half-year-old Jane Meserve speaks to us.

I am hijack. And kidnapped maybe. I don’t even know how to get here. It might be Alaska even. Nothing to eat because they don’t let me have food. So I am dying. I miss Mumma and she is very afraid. Mumma my sweet sugar. Help! Help! Hel . . . p!

Erika Locke, awake in the night.

Donnie Locke’s wife, Erika, mother of the dying baby Jesse, lies on her side under the thin summer sheet, afraid. Anguished for her baby’s pain. Anguished with knowing that a year from now he will no longer exist. But afraid also of everything now.

She remembers being told something, before Jesse was sick, but it impressed her big-time. Terry, her old friend. Terry, like Erika, young, but old friend all the same. Terry with blonde wild-woman hair. Sort of curly, but more like foam and sparks. Terry, who screams. That’s her regular voice; just telling you the weather, she screams. On the phone the voice cut into Erika’s ear, so Erika remembers it was Terry for sure who said this (screamed this): “Hospitals today can grab your house if you can’t pay a big bill! And the state eventually grabs your house if you use MaineCare and the hospital forces you to apply for MaineCare if you are eligible. Otherwise the hospital does the grabbing.”

Erika told Donnie.

He said that was dumb. “Hospitals can’t even charge interest and late fees.”

But then another friend, Kelly (Kelly Smelly, Donnie calls her because it rhymes), said, “It was the collection guys at the hospital. They called Matt”—her brother—”and said to pay bigger payments on his hernia operation or they’d put a lien on his property—and you ought to see his so-called property, it’s just his dinky shit trailer on a wedge of swamp—and they said they would assess his furniture too, and his pickup, because he only needed one vehicle, his beat-ta-shit car. His furniture!!! Television and a beanbag chair! They had him all taken apart for value. Kev”—her husband—”says fuckem, tell ’em to come take the hernia back’n’ stuff it up their asses.”

When Erika brought this bone home, Donnie said there had to be something lost in the telling here. But then Donnie’s cousin Steve was over one Sunday afternoon and told how the DHS had threatened to take his neighbor’s kids away if they couldn’t afford health insurance. They said, “No health insurance is child abuse . . . puts the kid in danger. You must apply for MaineCare.” Donnie said nothing to this. Ever since Jesse has been dying, Donnie is a quiet man who questions nothing.

The screen shrieks.

See the situation comedies that portray Americans who are just like you! They are cheery, bubbly folk with cute, easily-solved problems. And see here! The court trials, not actors, no way! This is reeeeeal court. See the troubles of the victims, their grief and need for revenge, and see those on trial, all these Americans whose troubles are mighty and ghastly and gory and outrageous and far WORSE than your troubles. See! Watch close!! Isn’t it astonishing!!! Real people on trial. Bad, ghastly, unapologetic people ON TRIAL. Watch close.

Erika Locke at the Egypt town office.

It has come to this. Erika is going to see about some “assistance.” She has put this off for a long time, afraid of social workers, the way once you make out that first paper, cash that first check, rip out that first food stamp, the government eye is on you. Everything about you, maybe even a print of your DNA, is theirs, quick as a computer key-tap. They, the mighty foot; you, the ant.

Erika is so afraid, she has seen small frisky stars cross her vision all morning ever since she got up.

She has worn her sea-green top with the lacy collar, which fits better since she started her little diet two weeks ago. And a denim skirt. Flip-flops. And socks. Early this morning her hair shined, but now the humidity has claimed it.

Behind the high counter is Harriet Clarke, the town clerk, reciting to someone on the phone all there is to know about purchasing a permit to move heavy equipment. Beyond is a computer with a deep-blue lighted screen with words that run along the bottom, then off the edge, then return from the other side to repeat. BE PATRIOTIC . . . CELEBRATE JULY 4 . . . BE PATRIOTIC . . . CELEBRATE JULY 4 . . . BE PATRIOTIC . . . over and over and over.

And now, repeating across Erika’s eyes, her own personal fear-stars. They drift along like something crushed, multiplying into hundreds.

Erika has heard that “social work” nurses will pressure you to let them inside your home to look around, scope the place out. They will interrogate your children. They look at their bodies for marks—bruises, scratches, burns—which all kids have unless you strap them to a chair for the first ten years of their lives. Erika has had three friends lose their kids temporarily, because of two bruises on one kid, a broken finger on another. The third had a burn. Three families. Two families loud and physical; the kids play as hard and rough as lion cubs. One family, quiet and nervous, nasty-neat types; the kids, too, very nervous, high-strung. None of these families are into heavy-duty punishment. But all three are poor.

A man saunters in from the hall, yellow, white, and blue motor vehicle registration papers in one hand. He wears glasses. A shave has given his pores a chemically scoured look. Wears a floppy madras fishing hat. A man of the legs-apart, arms-crossed, short, bullish, freckled, fifty-five-ish, hard-working, old-Yankee-blood, proud, proud, proud iron-fist-Republican variety.

The clerk finishes with the phone and asks Erika, “How you doin’ today? What d’ya need?”

“Who is it I need to see about some town assistance?”

The clerk has a hard face with lines around the mouth, but a soft expression. She disappears a moment, squatting down behind the counter at some floor-level drawer or cubby, then pops back up, paper in hand. She uses the flapping paper and her other hand to point, shape out, and underline her words. “Take this. Go over across the hall to the meetin’ room where it’s quiet. Pens on the tables there. Make this out the best you can. Sign it. Then come back and I’ll see what I can do, long’s you have everything you need: your last pay slips, W-2 forms, any proof of pay for the last twelve months. State card if you have it. That would save us a lotta trouble at this end.”

The man behind Erika has been listening in dead silence, moving his eyes over Erika’s breezy little sea-green top and plain brown hair with its sweet part, her round face and pink spots of emotion, one spot to each cheek—an ordinary girl, yes, like tens of thousands of sometimes giggling brown-haired American girls who, one overlapping the other at this hour, would make a vast plain of soft sturdy silhouettes that threaten no one.

In a voice cracking with anger, the man bellers, as if in a room of deaf people, “Harriet! When are you people going to do like Representative Connell’s been sayin’ an’ start fingerprintin” them so they’ll stop rippin’ the taxpayer off?!”

The woman behind the counter flushes. “Go on, David. Don’t start on that. I don’t need indigestion today.” And she laughs.

And Erika walks out. The hall walls are made of skinny vertical boards painted white. Her flip-flops make an echoey racket. The tall windows in the meeting room are all open, screened. Little stage at one end. Bare. The wood worn a warm yellow brown. She finds the can of pens. She takes her time, hoping the man will be gone.

But he’s not. When she returns to the hall, he’s there, hanging around by the bulletin board. He looks right at her, but he shows no recognition. Light from the doorway just touches his glasses as he turns away. And his face doesn’t really look angry anymore. Said his spiel and feels better now? Or is it that, without a gang, posse, or pack, his might is diminished? Here in the hallway, his bald-faced humanity is all he’s got.

Now seated in metal chairs between two heaped desks, Erika and the clerk go over what papers and proof of income will be needed. They talk awhile about how town assistance works. Sometimes, Erika’s voice seems uncharacteristically little-girlish. The clerk’s hair is white. Her blouse and slacks are white and cream. She tells Erika that even though Donnie’s part-time thirty-nine-hours-a-week job is not making ends meet, as long as they own two houses they cannot be eligible for assistance. “And all that land too.” The clerk sighs. By the guidelines, the Lockes and Gammons are not destitute, and destitute is what they must be. She suggests that Erika and Donnie go to the bank and mortgage one of their houses for a loan to live on for awhile.

Erika begins to smile in a most strange way. And the stars now as thick as TV snow make a cold pressure upon her eyes.

The woman, Harriet, who is on the other side of Erika’s silvery wall of stars, is now suggesting they sell the big house and live in the smaller one, or sell both places and keep two and a half acres for a trailer. On the market, they could get quite a sum for their real estate.

Real estate.

Erika speaks now, her voice squeaking with panic. “There’s really only one house. The place my mother-in-law lives in is really just a garage and bathroom. No stove or anything. The floor is cement. It’s just one room. She’s really with us in our house all day.”

Harriet smiles. “Can she work?”

Erika frowns. “She’s too shy. I mean she’s really shy.”

“Too shy to work?”

“Too shy, yes,” Erika murmurs.

“Can’t she watch the kids while you work?”

Erika blinks. She lowers her eyes and says with shame, “I want to be with my son.”

“But can’t she get a state check? And MaineCare? With her little one, she sounds eligible . . . and the fifteen-year-old. She would probably be eli—”

Erika interrupts. “It would be nice if Donnie could get a raise or something . . . or if they’d give him health insurance. It’s not like he’s goofing off! He works!” Her voice gets quite babyish. Lilty and brightly amazed.

Harriet laughs. “Well, nowadays they want us all working. Nobody stays home.” She laughs again. “This gives burglars jobs, too . . . all those empty houses!” And she laughs again.

Erika giggles girlishly, then looks down at her hands with shame. “I really just want to be home with the kids.”

Harriet snaps her pen, eyes sliding up and down the fine print of qualification rules. “Perhaps you can get Britta to move out. Turn her place back into a garage. Tear out the toilet and sink. The acreage doesn’t actually matter rule-wise, as long as it’s all part of your primary residence.”

Erika cocks her head, trying to make sense of this. No stars now. Just the clear hard edges of the clerk’s desks and the computer screen and map of Maine on the wall and the slight gurgle of realization. Of it: the vast order of things, the world’s logic, a global thing, even here in this room, especially here in this room, bouncing and leering and hilarious and formidable and growing bigger by the minute.

Erika says sweetly, “I just want a little help with my baby’s medicine, that’s all. Just his pain pills. Why can’t we get just that one thing without . . . all . . . you know . . . all that?”

“Like I said earlier, if you aren’t eligible for MaineCare, the hospitals have a program for that!” Harriet says cheerfully. “At least they help with a percent of certain types of medicine. Even doctors, working with the drug companies—they have a way of getting certain drugs free, I heard. There’s some paperwork on that. It all depends on income, though. And there are services through various agencies that could help with various areas of need. There’s a regional services coordinator who is in here twice a month who can help you make out the right papers to the various agencies. Just bring all your paperwork here and that other stuff you’ll need . . . oh, here . . . it looks here like you might be eligible for fuel assistance and winterization next winter . . . oh, and I think maybe . . .” She is running a finger over the small chart. “Family counseling services. You could get that. The services coordinator can—”

Erika interrupts. “I just want pain medicine. Just that.”

The clerk goes on studying the charts on her desk, snapping her pen. Her tongue makes a soft deep-thinking sound against her teeth. She sighs. “There was a pretty good state program for prescriptions, but the legislature gutted it last term. The waiting list on that one was impossible anyway.” She sighs again. “I can see you aren’t eligible for MaineCare. The second house will be a problem with them too. And your husband makes a little too much. It’s iffy. You could try. It depends on what your expenses are, although they don’t give you much leeway for expenses anymore. Maybe if he moved out! Your husband.” She says this jokingly.

Erika looks down at her hands. “It goes like this. We get his pay. We buy the medicine first. Usually after the medicine and bills, there’s just a little bit for groceries. We get the medicine first and pay the lights, and gas for the car, and everything like that . . . groceries last. We lost the phone. There’s just so much!” Her voice rises, childlike, not a shriek exactly, but a little thrilled thin edge to it. “It’s those doctors! And tests! When Jesse was first sick, I couldn’t believe how much they ask for those tests. Just the few times we went . . . it’ll take us forever to catch up! Then also Elizabeth, my husband’s oldest, she has trouble with her feet and legs: special shoes ’n’ stuff. Gas for Donnie to get to work is wicked. My mother-in-law’s youngest had some infected mosquito bites. Made her sick. That salve and antibiotic was wicked expensive. And this spring all the kids needed sneakers. Except Mickey. He just goes around like a bum. And then the roof leaked! It was only in one little spot, but even that was four hundred dollars to fix! Everything is just so much! Liability insurance is more this year. And my driver’s license had to be renewed last month, for the picture and everything . . . and then you know our property taxes; we’ve stayed right up with those . . . and then propane; we ran out of that but got some last week . . . and toilet paper and wax paper and a new can opener ’cause the other busted and we can’t open cans with anything else, and the—”

The clerk has put up her hand. “I’m sorry! The state guidelines determine most of this, even for the towns. At town meetin’, we only vote on the total recommended amount for the year. But the guidelines for eligibility are set. It’s not up to me. I hear you, Erika, but it’s not up to me. I’m sorry.”

She has used Erika’s name. The warm sound of her name. This woman’s voice, the family resemblance of her mouth and eyes to so many others in town. The sweet humid summer air that has oozed in the open windows, mixed with the imposing woody old smell of the building, these things that are permanent and emollient and too beautiful. For the first time since Jesse’s cancer, Erika breaks down in front of someone. So unpretty. Her crying is like snorting.

The clerk shoots up out of her own seat and gets Erika a box of tissues, one thing she, as a human being, can do for another human being, a simple gesture, unencumbered, unprohibited, not too costly.