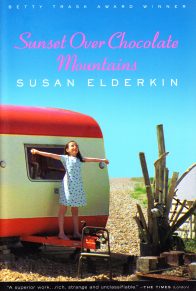

Rectangles of white-bordered posters glimmer through the mealy grey air. Their edges snake where they haven’t been fully stuck down. Along a shelf is a row of stones, small enough to fit in the palm of a child’s hand. Near the far wall a spray of blond hair crouches on a pillow like a spider. There’s the sound of shallow, fretful breath.

Suddenly the hair flies into the air, hangs suspended for a moment like a ball at the top of its toss, then drops back down again – a fresh corner of pillow this time, a little cooler than before. Maybe now he’ll be able to get to sleep. But no: a second later the hair flies up again, an elbow jabbing angrily at the sheet.

This is Billy, we say.

Ah, says the wind, so this is him. What’s all the tossing and turning about? Is it the heat?

No, no, he’s used to that.

Was I making too much noise in the cabbage gums?

No more than usual. Look, just there, on the bridge of his nose. See that dent?

Like a drawstring tugged tight?

Yes.

A gathering up of his confusion?

That’s right. All the unanswered questions.

I see, says the wind. No wonder he can’t sleep.

Quite.

Still don’t know what you lot are bothering with him for.

Though curious enough at first, the wind doesn’t really care about this boy – and why should it? It has no need of people; it doesn’t depend on them like we do. Instead it curls around the room looking for something to disturb, a loose sheet of paper to flutter to the floor, a pencil to roll off a chair. But the contents of this room are disappointingly static. On the floor by the bed is a thin, hardback book called The Universe, face down, its pages buckled and trapped beneath it. On its cover is a picture of the planet: swirls of white and blue and green like blobs of ink twirled round with a nib, and all around it is the perfect blackness that sets the scenes for this boy’s nightmares – more like sensations than nightmares, when gravity has lost its hold and he’s falling through space, arms lashing out for something to hold onto, all the time falling faster and faster and still the blackness goes on, plenty more where that came from – ah yes, an infinite supply. Will it ever come to an end?

We’ve all had dreams like that, sneers the wind. They aren’t anything special.

But this boy beneath the sheet, this boy that we are starting to love, has more than his fair share of solitary fears. He is small for his age, skinny. The wind ruffles the edge of the sheet so that we can get a peek – yes, there it lies, meek and pale as a cracked brazil nut just out of its shell. Any day now he will turn the corner, sprout hair, an Adam’s apple budding in his throat, those arms and legs shooting out and down until they’re long and gangly with heavy hands and feet on the ends – just like his father’s, too big and clumsy to be much use. But he’s not quite ready yet. A thin arm whips up as he flings himself onto his back, exposing a slight, honey-brown torso, ribs showing through like the roots of a tree. Fingers curled on the pillow, as if he wants to ask a question.

Excuse me, Mrs Tucker, I don’t understand.

What don’t you understand, Billy?

Any of it.

What do you mean, any of it?

Her irritation curbs his confidence but doesn’t shut him up completely.

What we’re doing here. What it’s all about. Who we’re supposed to go to for the answers.

See the anxious eyeball flickering beneath the lid? It is as if he refuses to make the transition into adolescence until he gets some answers. And who can blame him? Not us. Certainly not us.

Such ridiculous questions, mutters Mrs Tucker.

It doesn’t make sense, that’s all. How am I supposed to know what’s right and what’s wrong? I don’t know who to ask.

Even as we watch he begins to slip, the muscles in his cheeks sliding into softness, the delicate mouth crushed against the pillow where a little pool of dribble will collect before morning. In a snap of a finger, he’s gone. Ah, what a shame, Billy, we appear to have run out of time. Jiss have to wait until tomorrow, won’t we?

Rebutted by Mrs Tucker, the useless cow.

Before our eyes, the unconscious body draws its extremities in towards the warmer core: the knees pulling up, the elbows folding in, the freckled nose burrowing down. And so the questions draw in too, their curious searchlights aimed now at his steadily thumping heart. If there are no answers out there, they will just have to make do with whatever they can find inside him: instincts, primeval knowledge – whatever they call them these days. Perhaps they will be found stencilled into the walls of his gut, secreted down blood-red tunnels, tucked inside folds of tissue like fossils.

A tightly twisted spiral of a snail shell preserved in all its wondrous detail. Palaeozoic, Mesozoic, Cenozoic. All these epochs hidden inside the body of little Billy Saint.

The bridge of his nose is smooth now, perfect as the bowl of a spoon. And the wind is bored. There’s nothing to play with here and it wants to move on – it’s what winds do, after all – and we’ll go with it, although we’ll be back to see this boy again. Once we’ve made up our minds, we never back down – and anyway, who are we to be choosy these days? The wind takes one last spin around the room and then, childishly, when we’re not looking, darts behind one of the slouching posters so that it flops right off the wall, doubling over in a little thunderclap of stiff paper, and the boy sits bolt upright in his bed, blinking in surprise, sees nothing but a disembodied square of pale curtain floating at the window, hears a quick rustling of the gum trees outside.

And then everything goes quiet.

Part I

the largest pair of knees

–How long you gunna take to fill that bedpan?

He opens his eyes to find himself confronted by the largest pair of knees he has ever seen. They are bold and black, the skin paler where it’s stretched over the humps, darker in the dips and hollows. They are not a perfect pair: the left is more bulbous than the right. It is as if they had been crafted by hand.

His eyes travel upwards. Thick, folded arms struggle to extricate themselves from beneath a heavy wedge of breast. When he reaches her face he sees that she is a full-blood. Her solid, protruding brow reaches right over the black eyes like the overhang of a cliff.

The nurse squints up at a bag of saline hanging from a metal stand. A plastic tube dangles down and disappears beneath a bandage on the back of his hand. Her lips move, counting drips. Four, five, six. Nine, ten, eleven. Then she flicks up the edge of his sheet with a finger and gives a small, breathy cry of exasperation.

– Get a move on, wontcha.

She is sharp with her high-pitched words, as if they are prickles in her mouth she has to spit out.

He turns away from her, mortified.

It’s the position.

Want me to get it moving?

Out of the corner of his eye, he can see that she is wriggling her forefinger: a child’s imitation of a mouse. Instinctively, he jerks his buttocks away and almost slips off the pan.

Ya kiddin.

She waits just long enough for him to realise his mistake.

You bet I am. You’d hev to be prettier for that.

She relishes the look on his face, practically licks her lips at it. Eyelids lowered to contain her satisfaction, she turns her body in the way that heavy people do, moving the chair to one side to save herself the job of stepping around it, and saunters off, her high-boned arse swilling from side to side like brandy in a glass.

She’s smiling to herself, he can tell. At the door of the ward she looks around and sniggers again.

Cecily thinks the whole business is hilariously funny. Billy can’t remember the last time he gave someone so much cause for amusement. He knows her name is Cecily because she has a badge pinned to her uniform. It hitches up the thin cotton fabric so that one breast looks higher than the other. The uniform is made of pale-blue graph-paper hatches.

He has an urge to use her name – both out of a desire to feel those Cs on his tongue, and to show that he likes her, that he might soften for her – but he hasn’t had a chance yet, and he’s not one to force these things. She reminds him of the women from back home, with her harsh voice and her air of absolute disinterest in what’s going on around her. She has a way of standing still amid the scurrying, her gaze skimming the tops of people’s heads.

Cecily.

It doesn’t suit her one bit, he decides, the hard rim of the bedpan digging into his coccyx. Far too delicate, ethereal a name for someone so solid, so real.

A woman in a flapping white doctor’s coat, her hair scraped back in a severe bun, sits on the edge of his bed and looks at him with unconcealed impatience. She has introduced herself simply as Ann, as if everyone should know who Ann is, what Ann does. Only by scrutinising her badge does he discover that she’s a psychiatric consultant, and that her full name is Ann Gould. Billy responds with contempt: she, after all, is the one who talks to the freaks.

– Can you tell me what you remember? she asks, rearranging the pink and green forms on her clipboard.

Billy’s not in the mood. He suspects that any probing will push his already sketchy memories even further into the shadows. But she presses him, says there’s a cop coming along shortly who will bully him into giving a story, any story, so he might as well get one worked out. She prompts him, as if he were a child.

This incident on the train. There was a fight, yes?

Surely the other bloke’s filled you in already.

– I need to hear your side of the story. The hows and whys of it. I’m not a fucken philosopher.

She raises the narrow arcs of her plucked eyebrows, lets the disdain spill freely from her eyes. Bullies come in many disguises, he thinks. He sighs.

Yeh, we had a fight, he says.

We?

That man, the American tourist, and me.

Describe him, please. For the record.

– Big and fat. Video camera slung over “is shoulder. White knee-high socks, freckled thighs. About as much subtlety in him as a fork-lift. He tails off, fragments of memory beginning to surface now. He lets them go, a separate strand from the story he is going to tell her.

Go on.

He wouldn’t get out of me way. He was sittin in me seat.

Sitting in your seat? But you didn’t have a seat –

– And so you had to hit the bugger, interjects Cecily. Unseen by either of them, the black nurse has crept into the curtained-off cubicle and is rearranging the glass of water and box of tissues on his bedside table, even though neither has been touched. Evidently she hadn’t wanted to miss Billy’s account.

– He was that shocked you’d have thought he didn’t know what fists were for! She is holding back a snigger but it escapes, a little gumpf of a snort, and she decides to give in to it. She stands up straight and wipes a tear from her eye. – Oh, you shoulda seen his face when they brought im in! It was like “e was saying, This wasn’t in the tourist brochure!

Billy can sense a stiffening in Ann’s body at the foot of his bed, forcing herself to sit out this interruption in good humour. Her pointed features are pinched shut like the clasp on a purse.

Cecily –

– Seemed to think Billy had bin planted out in the bush for their entertainment, part of the tourist show. Out to your left is a wild bushman, a very lucky sighting, you don’t see em often.

Cecily, I want to hear Mr Saint’s version of events. She nods at Billy.

Go on.

Billy shrugs. He was enjoying Cecily’s jokes. – I don’t remember any more, he says. Everyone was staring at me. I don’t know why.

Ann cocks her head. – I can tell you why, Mr Saint. You were blistered from the sun and rank as a five-day-old carcass. The driver of the Ghan Express saw you lying between the steel sleepers, as though you were waiting either to be hit by the train or to be carried back towards civilisation. Towards life. If he hadn’t been going so slowly it would certainly have been the former. I don’t think you appreciate how lucky you are.

Cecily is blowing her nose now with a cotton hanky and Billy smiles as he watches her blocking one nostril and then the other. She doesn’t look like the women back west any more. She is just a nurse, at home enough here to disrupt the doctor’s interrogation and not care. Billy is impressed by her, how she has found a niche for herself in this white institution, hoisting herself firmly out of no-man’s-land and dumping her bulky frame down here as if she had never doubted her right to it all along. – I was thirsty, Billy says quietly. I didn’t want to die. I was looking for a drink of water.

And so you thought you’d hitch a ride.

She bores in with her determined eyes. Billy turns away, scrutinises the cream and tan geometric pattern on the curtains by his bed.

Do you remember anything else at all, Mr Saint?

Yeh, I do. They were playing Casablanca on TV.

Afterwards, Cecily wheels him to the bathroom and positions him squarely in front of a full-length mirror. She says she wants to get him neatened up before the cop arrives. The bathroom is a large, rectangular room, fitted out for the elderly and infirm – metal rails either side of the toilet, a raised plastic seat. Billy hadn’t thought he’d find himself using a bathroom like this just yet.

He slouches in silence while she opens a cabinet and takes out a pressurised can. She squirts a ball of foam on to her palm and offers it to him as if he were a horse, a white cloud cupped beneath his mouth. He sits there sullenly, intent on his humiliation. She waits a full half minute then she picks up his chin and slaps the foam against his jaw. Specks of it spray out like the froth of a wave hitting rock. Billy looks up with the shock of it, catches her eyes in the mirror. They direct him to his own. And there he is, not yet twenty-four years old but going on ninety – the face of a man who has travelled to the limits of his existence and witnessed something horrible lying beyond. The blue-ringed eyes are sunk deep in his skull, the skin falling away beneath with all the sagging hopelessness of a bloodhound. Billy notices with what little curiosity he has left for such things how bony his nose has become, how it’s topped with a raised black scab. How the skin on his cheeks is blistered and raw in some places and peeling off in others. Straws of pale hair stick out in odd directions and clots of old blood are trapped in the straggles of beard around his mouth. Jesus, it was an ugly beard – not a thick, curly, ruddy one like Rossco’s, but a scrawny, willowy thing, like the greasy tufts you see curling over the collar of a bagman.

Fucken “ansome fella, ay.

Cecily’s face is composed. She can be the consummate professional when she chooses to be.

It’s all looking a bit crook now, but it’ll soon come right.

He’s touched by the tenderness in her voice. She holds up a disposable razor, her pink tongue pushing through the gap in her front teeth. Go on then, Billy says softly.

She spreads the foam to the edge of his jaw. Then she holds the skin taut with the span of two fingers and bends close. Concentration ruckles her brow. Billy keeps his eyes open, daring himself to stare at the black skin close up, the individual pricks of the pores, the few stray hairs encroaching onto the temple; daring himself not to look away.

In the quiet of the bathroom, they listen to the sound of the stubble being shorn. For Billy, it is something to cling to, the first unequivocal sound in weeks. Cecily makes no mention of the tiny white scars that appear on the surface of his face like flotsam in the razor’s wake.

Copyright ” 2003 by Susan Elderkin. Reprinted with permission from Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.