News Room

Every year, the last week of September is officially Banned Books Week. As the American Library Association—who promote the annual campaign, along with Amnesty International—explain on their website, BBW “brings together the entire book community—librarians, booksellers, publishers, journalists, teachers, and readers of all types—in shared support of the freedom to seek and to express ideas, even those some consider unorthodox or unpopular.”

(Besides suppressed literature, Banned Books Week is also a good opportunity to celebrate the legacy of legendary librarian and free speech advocate Judith Krug, who was pivotal in its establishment. In 2009, Dorothy Samuels wrote a lovely appreciation for the New York Times, which you can read here.)

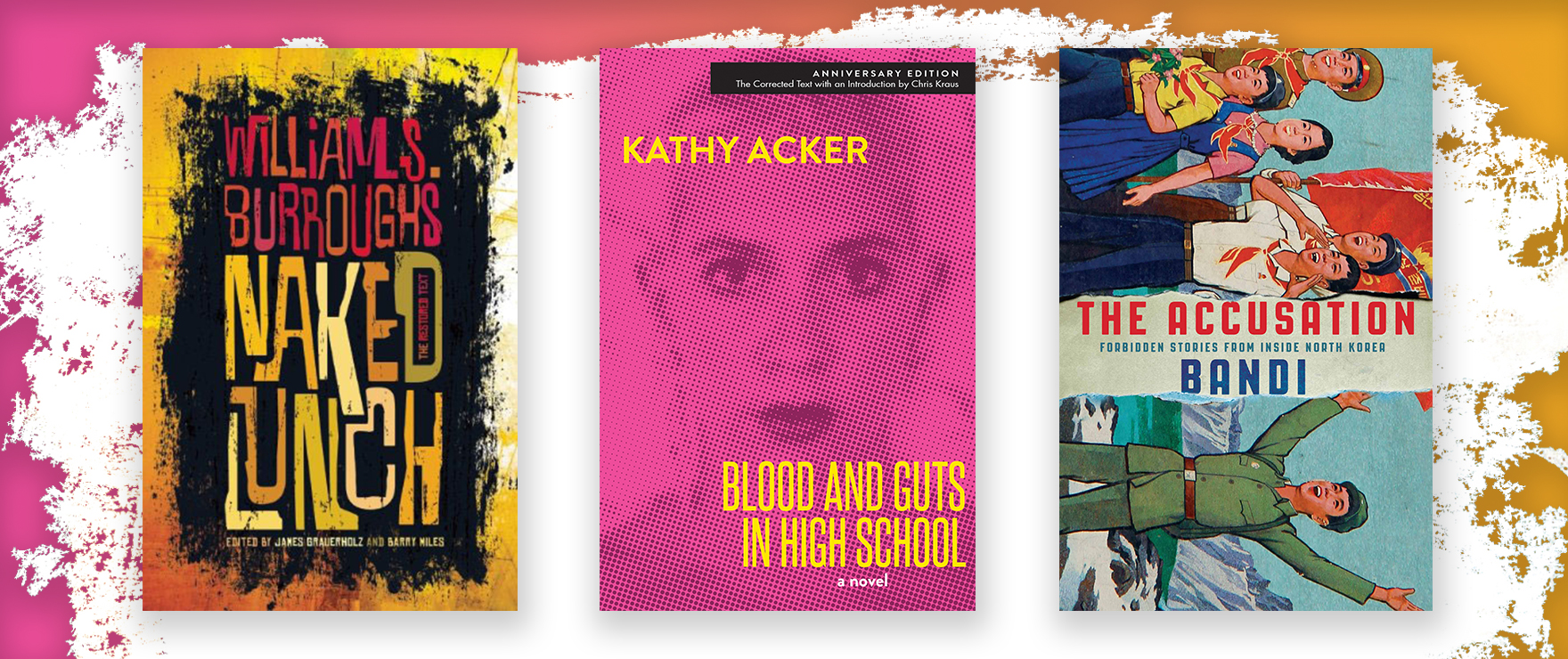

Here are just a few favorites from our backlist that have been banned or challenged in varying times and places:

The Accusation / Bandi / Translated from the Korean by Deborah Smith

Talk about a banned book — the North Korean government so disapproves of the short stories in this walloping (and history-making) collection that they had to be smuggled out of the country and published pseudonymously. “Bandi” is Korean for “firefly,” and like that small creature, which illuminates an enveloping darkness, these seven stories, set during the period of Kim Jong-Il’s leadership, throw light on different aspects of life in this most bizarre and horrifying of dictatorships.

Blood and Guts in High School / Kathy Acker

Shortly after its publication in 1984, Acker’s screaming asteroid of a novel was officially banned by both Germany and South Africa. Author Lidia Yuknavitch adds that it “may as well have been banned in America, since it only existed in a kind of subterranean, black market underworld if you were by chance a young woman reader.” A masterpiece of surrealist fiction, this is the book that established Kathy Acker as the preeminent voice of post-punk feminism—long before her now-legendary interview with the Spice Girls—and it’s available more widely than ever before.

Naked Lunch / William S. Burroughs

Today recognized as a spasmodic anthem of experimental literature, Burroughs’s legendary novel was first published in 1959 to a flurry of legal challenges and attempted suppressions. These had begun even before Grove Press first brought the book out: early that year, editors at Big Table magazine had been arrested on obscenity charges for mailing out an issue that serialized several excerpts. They were convicted. After we published it in 1959, Naked Lunch was banned for obscenity in Los Angeles and Boston. The California ban was overturned by a state court in 1965; the next year, the Massachusetts Supreme Court likewise ended the Boston ban, after a hearing in which Norman Mailer testified that Burroughs was “whatever his conscious intention may be… a religious writer,” and described the book as “a vision of how mankind would act if man was totally divorced from eternity.”

The Years, Months, Days / Yan Lianke / Translated from the Chinese by Carlos Rojas

There’s a reason the Financial Times called sixty-year-old Yan Lianke “China’s most feted and most banned author.” Feted indeed — his recognitions include the Lu Xun Literary Prize and the Franz Kafka Prize, and he has been shortlisted for still many more, including the International Man Booker. But the subject matter he confronts in his visceral and acclaimed prose—the many contradictions of contemporary Chinese society, and the heavy hands laid on it by the apparatus of official repression—have won him few fans in government. Besides having many of his books formally censored, Yan has spoken of the challenges Chinese authors face “because we’re not aware of the restrictions we have internalized: the most chilling thing is the way we censor ourselves. We need to acquire a degree of inner freedom.” We are proud to publish in English translation a number of Yan’s books currently illegal in China, including Serve the People!, Dream of Ding Village, and The Four Books, and to be bringing out the harrowing, surreal The Day the Sun Died this December. Like so much of Yan’s work, the two novellas of The Years, Months, Days offer a chilling composite parable of life in that country today.

Waiting for Godot / Samuel Beckett / Translated from the French by, ahem, Samuel Beckett

Given that it is arguably the play of the twentieth century—and that it depicts no obscenity beside that of humanity’s existentially bewildered condition—one might not expect to find Waiting for Godot on lists of suppressed literature. But Godot has, indeed, been banned: for years by the government of East Germany, and again, decades later, by the authorities who run the US military detention facility at Guantánamo Bay. In guessing at the reason behind this seemingly incomprehensible prohibition, Tony-nominated theater director David Leveaux speculated that “perhaps it’s because, somewhere at the core of the play’s enduring and insurgent beauty, it possesses the same quality [Beckett] once ascribed to one of his favorite rugby players — that he was ‘capable of genius when the light is dying.’”

Tropic of Cancer / Henry Miller

In the twenty-seven years that elapsed between its initial 1934 publication and the lifting of US government restrictions on it, Tropic of Cancer may have embossed itself on American mass consciousness as the banned book par excellence. The reasons for its attempted suppression are apparent enough: the novel chronicles with unapologetic gusto the bawdy adventures of a young expatriate writer, his friends, and the characters they meet in Paris in the 1930s. After we published the first US edition in 1961, more than forty wholesalers and booksellers were prosecuted on obscenity charges for distributing it. In the words of writer Felice Flanery Lewis, there was soon a “massive effort to assist every bookseller prosecuted, regardless of whether there was a legal obligation to do so,” spearheaded by two legends: longtime Grove publisher Barney Rosset, and literary free speech lawyer Charles Rembar. At first, results were mixed, with some jurisdictions relaxing their prohibitions, and others—including New York State—upholding them. Finally, in its landmark 1964 decision Grove Press, Inc. v. Gerstein (hi mom!), the US Supreme Court declared the bans unconstitutional, and ruled that Tropic of Cancer was a work of art with “redeeming social importance.”

Happy Banned Books Week, everyone! A fine occasion to read deeply, illicitly, and well.