It’s over.

Holidays. Holidays. Holidays.

For three months. An eternity.

The beach. Swimming. Bike rides with Gloria. And the little streams of warm brackish water among the reeds. Wading knee-deep, looking for minnows, tadpoles, newts and maggots.

Pietro Moroni leans his bike against the wall and looks around.

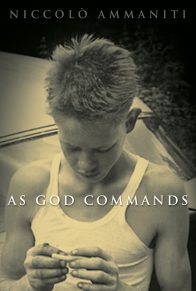

He’s twelve years old, but small for his age.

He’s thin. Suntanned. A mosquito bite on his forehead. Black hair cut short, in rough-and-ready fashion, by his mother. A snub nose and large hazel eyes. He’s wearing a white World Cup T-shirt, a pair of frayed denim shorts and translucent rubber sandals, the kind that make a black mush form between your toes.

Where’s Gloria? he wonders.

He threads his way through the crowded tables of the Bar Segafredo.

All his schoolmates are there.

All waiting, eating ice creams, trying to find a patch of shade.

It’s very warm.

For the past week the wind seems to have disappeared, moved off somewhere else taking all the clouds with it and leaving behind a huge incandescent sun that boils your brain inside your skull.

It’s eleven o’clock in the morning and the thermometer shows thirty-seven degrees Celsius.

The cicadas chirp away obsessively on the pines behind the volleyball court. And somewhere, not far away, an animal must have died, because now and again you catch a sickly whiff of carrion.

The school gate is closed.

The results aren’t up yet.

A slight fear moves furtively in his belly, pushes against his diaphragm and restricts his breathing.

He goes out of the bar.

There she is!

Gloria is sitting on a low wall. On the other side of the street. He goes across. She pats him on the shoulder and asks: “Are you scared?”

“A bit.”

“So am I.”

“Come off it,” says Pietro. “You’ve passed. You know you have.”

“What are you going to do afterwards?”

“I don’t know. How about you?”

“I don’t know. Shall we do something together?”

“Okay.”

They sit there in silence on the wall, and while on the one hand Pietro thinks she looks even prettier than usual in that light-blue towelling T-shirt, on the other he feels his panic growing.

If he considers the matter rationally he knows there’s nothing to worry about, everything was sorted out in the end.

But his belly is not of the same opinion.

He wants to go to the bathroom. There’s a bustle in front of the bar.

Everyone comes to life, crosses the road and throngs around the locked gate.

Italo, the school caretaker, comes across the yard, keys in hand, shouting: “Don’t push! Don’t shove! You’ll hurt yourselves.”

“Come on.” Gloria heads for the gate.

Pietro feels as if he has two ice cubes under his armpits. He can’t move.

Meanwhile they’re all pushing to get in.

You’ve failed! says a little voice.

(What?)

You’ve failed!

It’s true. Not a presentiment. Not a suspicion. It’s true.

(Why?)

It just is.

There are some things you just know and there’s no point in wondering why.

How could he have imagined he’d passed?

Go and look, what are you waiting for? Go on. Move.

At last he breaks out of his paralysis and joins the crowd. His heart beats a frantic little march under his breastbone.

He uses his elbows. “Let me through . . . I want to get through, please.”

“Take it easy! Are you crazy?”

“Keep calm, you idiot. Where do you think you’re going?”

He receives a couple of shoves. He tries to get through the gate, but because he’s so small the bigger pupils just throw him back. He drops down on all fours and crawls between their legs, circumventing the blockage.

“Calm down! Calm down! Don’t push . . . Keep back, for Chr . . .” Italo is standing beside the gate and when he sees Pietro the words die in his mouth.

You’ve failed . . .

It’s written in the caretaker’s eyes.

Pietro stares at him for a moment, then runs forward again, towards the steps.

He bounds up them three at a time and enters.

At the other end of the entrance hall, beside a bronze bust of Michelangelo, is the noticeboard with the results.

Something strange is happening.

There’s this boy, I think he’s in 2A, his name is . . . I can’t remember his name, who was going out and he saw me and stopped, as if it wasn’t me standing in front of him but some kind of Martian, and now he’s looking at me and nudging another guy, called Giampaolo Rana, his name I do remember, and he’s saying something to him and Giampaolo has turned round too and is looking at me, but now he’s looking at the noticeboards and now he’s looking at me again and speaking to another boy who’s looking at me and another boy’s looking at me and everyone’s looking at me and everything’s gone quiet . . .

Everything has gone quiet.

The crowd opens out, leaving him a clear path through to the class lists. His legs take him forward, between two wings of schoolmates. He goes on till he finds himself a few inches from the noticeboard, being pushed by the kids arriving after him.

Read it.

He looks for his section.

B! Where is it? B? Section B? One B, Two B. There it is!

It’s the last sheet on the right.

Abate. Altieri. Bart . . .

He scans the list from the top downwards.

One name is written in red.

Somebody’s failed.

About halfway down. Somewhere around M, N, O, P.

It’s Pierini.

Moroni.

He shuts his eyes tight and when he opens them again everything around him is blurred and wavy.

He reads the name again. MORONI PIETRO FAILED He reads it again. MORONI PIETRO FAILED

What’s the matter, can’t you read?

He reads it yet again.

M-O-R-O-N-I. MORONI. MORONI. Mor . . . M . . .

A voice echoes in his brain. What’s your name?

(Sorry? What did you say?)

What’s your name?

(Who? Me . . .? Er . . . Pietro. Moroni. Moroni Pietro.) And up there it says Moroni Pietro. And right next to it, in red, in capitals, in big capital letters, failed.

So that feeling was right.And there he was hoping it was just the usual sickening feeling he gets when he’s due to have a piece of classwork returned and he’s ninety-nine per cent sure he’s done really badly. A feeling which always turns out to be unjustified because, as he knows, that microscopic one per cent is worth far more than all the rest.

The others! Look at the others.

PIERINI FEDERICO PASSED

BACCI ANDREA PASSED RONCA STEFANO PASSED He looks for traces of red on any of the other sheets, but they’re all solid blue.

I can’t be the only one in the whole school who’s failed. Miss Palmieri told me I’d pass. She said everything would be fine. She prom . . .

(No.)

He mustn’t think about it.

He must just leave.

Why did they pass Pierini, Ronca and Bacci and not me?

Here it comes.

The lump in the throat.

A spy in his brain tells him: Pietro, old pal, you’d better get out of here quick, you’re going to burst into tears. And you don’t want to do that in front of everyone, do you?

“Pietro! Pietro! What does it say?”

He turns round.

Gloria.

“Have I passed?”

Her face bobs up at the back of the crowd.

Pietro looks for Celani.

Blue.

Like all the others.

He tries to tell her, but can’t. He has a funny taste in his mouth. Copper. Acid. He takes a deep breath and swallows.

I’m going to throw up.

“Well? Have I passed?”

Pietro nods.

“Yesss! I’ve passed! I’ve passed!” Gloria shrieks and starts hugging the kids around her.

Why is she making such a fuss about it?

“Hey, and what about you?”

Answer her, go on.

He feels sick. Some hornets seem to be trying to get into his ears. His legs are limp and his cheeks are on fire.

“Pietro! What’s the matter? Pietro!

“Nothing. I’ve only failed, that’s all, he feels like answering. He leans back against the wall and slides slowly down to the floor.

“Pietro, what’s the matter? Aren’t you well?” she asks him and looks at the lists.

“Didn’t you pa . . .?

“No . . .”

“What about the others?”

“Y . . .”

And Pietro Moroni realises that everyone is staring at him and crowding around him, that he, sitting there in the middle, is the jester, the black sheep (red sheep) and that Gloria is on the other side too, now, with all the others, and it doesn’t matter, it doesn’t matter at all, that she’s looking at him with those Bambi-like eyes.