He had noticed at an early age how everywhere looks all right on the map. Peel Park, a brutal wasteland where he had been headbutted, spat at and beaten almost to death, was, on the page of Daniel’s Manchester,

an inviting-looking green rectangle: the kind of place, a foreigner might have concluded – glancing idly at the book in the reference section of some distant library – where a man would linger over a glass of Sancerre before walking his lover back towards the city lights at dusk.

A few pages on in his street plan, Eastern Circle, where Daniel Linnell was born – a road which he had last seen weirdly illuminated by the torched remains of a heavy German car – had a precise, geometric form which suggested scrupulous order and decency. The map was one of life’s more perverse deceptions and Daniel, as a boy, had even come to see it as a source of comfort.

Shut up in his room in the wake of some minor beating, he would pick up the A to Z, locate the scene of his most recent torment, then stare silently at the street as it now appeared – unthreatening, timeless, and perfect. It would not be too much to say that in these moments, with his map in his hand, he found a sort of grace. Which made it all the more remarkable that every time he saw it, even on paper, his spirit was broken by Maple Street.

Remarkable too, because – in a balanced inventory of his setbacks in Maple Street, London W1 – incidents involving major violence, terror, and sexual humiliation (among the things which had driven Daniel most swiftly to his map cupboard) were almost entirely absent. But balanced, in Daniel’s experience, was never quite the word for Maple Street.

He had gone there to work at Resolve, a private therapy practice, where he was completing his probationary year as a counsellor. The centre offered a well-intentioned, if expensive, service which, because many clients contacted it over the phone, was unkindly described by one of Daniel’s colleagues as `the Samaritans with a swipe machine’.

Resolve occupied the entire ground floor of a Maple Street office block. There were four consulting rooms; each had a door leading off a large reception area, where there would generally be one or two clients creaking anxiously in the cane armchairs. Waiting customers could choose between reading style magazines from the transparent coffee table (current issues bought by the practice, not old, donated copies – a sure sign, Daniel said to himself when he first saw them, of shadiness) or staring at the two angel fish who gaped vacantly back at them from the aquarium. Guy Montgomery, Resolve’s founder and director, had installed the large fish tank in the hope it would inject a feeling of medical expertise, because dentists had them.

And to work at Resolve – Linnell still cringed every time he heard that name – you didn’t need medical expertise. Daniel, who had taught English to business students in Limoges for a year, then drifted in and out of temporary jobs for five years after leaving college, had been surprised and delighted to learn that his degree in French and a Certificate in Humanistic Counselling from a six-month course of evening classes, which he had taken out of boredom as much as anything else, was enough to get him start as a mental health professional.

And now, as Daniel neared the end of his probationary period Montgomery and his two partners agreed he was good – even brilliant – at dealing with intense cases of emotional damage. He had an unusual combination of attributes: a keen, if unfocused, desire to assist humanity and a capacity for detachment from other people’s pain. He might have been a GP, a news photographer, or an executioner. He was their kind of man.

Guy Montgomery himself had been a repertory actor until he had a nervous breakdown in the mid-eighties. It came on suddenly, according to the version that circulated in the Resolve staff room, when he first burst into tears, then lit a cigarette, while on stage in Sheffield playing Hotspur in Henry IV. Even then, so the rumour went, it was only when the sprinkler system went off over the stage that the conscript audience of fifteen-year-olds noticed that anything was up. When Montgomery recovered, he took a degree in psychotherapy. After a year’s service with another London counselling centre, he set up Resolve with the encouragement of his less fragile wife Linda, who was in charge of the books.

The perfect elocution Montgomery had retained from his theatrical training made him sound insincere – which, for the most part, he wasn’t – and, though he had never set foot on a London stage, he was prone, especially at social events, to indulge in small, outdated gestures of Metropolitan flamboyance, such as panatella cigars or hats. His real Christian name was Colin.

`If he knows so much,’ said Deborah, one of Daniel’s fellow probationers, when she heard Linnell defending him, `why does he wear that cravat?’

Resolve clients were referred to by their first name only, like saints. For the benefit of customers who were desperate, or abroad, there were four soundproofed booths at the end of a short corridor, each of which contained a telephone and a small desk. The booths were staffed twenty-four hours a day, and were charged to a caller’s credit card by the minute. On the phone, as in one-to-one consultations, Daniel had been taught to remain silent for the most part and, when he did speak, to steer the client towards their own solution or, as Montgomery preferred to term it, `resolve’. It was a technique that went down well with most callers who were not, on the whole, great listeners.

`It sometimes occurs to me,’ said Lynne, one of the senior therapists, `that if I just left the phone on the table and nipped out for a dhansak, when I got back they’d be sorted.’

Such irreverence in the private conversations of the staff, like the `sin per minute’ league table Daniel had posted on his locker door, would have horrified the customers, but did not necessarily denote a lack of compassion; it was just one way of not going mad. The dangerous gulf in tone between the robust talk in the staff room and the hushed, measured exchanges in the consulting areas had been brought grotesquely into focus a couple of years before Daniel arrived, when a therapist who was on the telephone in reception fixing up a new appointment for a middle-aged psychotic with deviant tendencies, noticed that his fellow counsellors were preparing to leave for the pub. Reaching for the privacy button on the switchboard, he called out, `I’ll see you in a minute, I’m tied up with the sheepshagger’ but hit speakerphone by accident, so that he and his colleagues remained frozen in a horrified tableau, as the client’s voice called out his terrible response: `I heard that pal.’

Montgomery initially tried to deny that the incident had ever happened, then found he couldn’t, and began to address it directly in his introductory staff seminars. On the front of his plywood clipboard, which was generally hidden by his patient’s notes, Daniel had written the sheep man’s words, as a warning to himself, in red felt pen.

Serious psychiatric cases were rare, though Daniel did see one, Elliot King, on a regular basis. King, who was in his late-fifties, was an American saxophonist. At the height of his success, in the seventies, he’d led his own band in the States, where he enjoyed a cult reputation among fans of contemporary jazz. As his appeal had faded, he’d worked increasingly in Europe, and settled permanently in London in the eighties. Even now, Daniel knew, there was a rack of King’s records in the Oxford Street music stores and, when he was well, he could still fill the Festival Hall.

Daniel’s own attitude to modern jazz – dominated by loathing and ignorance – turned out to be no obstacle, as King never spoke about his career, except in his very early years in Birmingham Alabama, when his parents had trained him to tap dance. `I can still do that, you know,’ he once told Linnell, getting to his feet and circling the room, each foot gently tapping out three beats as he walked. It was an effortless movement, and he did it without ever breaking his stride. Sometimes he’d do it when he was waiting in reception, to let Daniel know he’d arrived. `When you hear that tap man,’ he said, `you know I’m out here for you. You hear that, you get that last damn maniac out of there.’

Elliot had spent periods as an in-patient in psychiatric wards. `I don’ ever want to go back there,’ he told Daniel. `Here I get you. There, there’: the doctors always messing with me.’

`Here,’ Daniel said, `you pay.’

`There,’ Elliot said, `you get robbed. I got all my music robbed there. And my cigarettes. And my telephone money.’

He tended to view his counselling sessions less as the solution to his problems, more as a diversion from them. He was softly spoken and, unlike many musicians, his hearing had survived unimpaired. He used to complain if Daniel spoke too loud to him. `Hey,’ King would say. `Easy. My ears are still OK – God knows how. It’s my mind that’s gone.’

Elliot had built up an encyclopaedic knowledge of the hundreds of small towns he had visited in his years on the road. From time to time, without warning, Daniel would fire a place name at him – Lubbock, say, or Duluth, or Des Moines – and Elliot would have to supply three points of information, like area code, population, or most famous former inhabitant. It had become a game between them. In his darkest moods, which were rare but very frightening, the musician was also a religious obsessive, whose nine-inch kitchen knife (`Mike’) had been urging him to commit murder. In desperation, Daniel had finally advised Elliot, who was six foot two and weighed two hundred pounds, to bury the knife in the back garden, a proposal that appeared to put an end to the trouble.

If a threatening incident did arise, counsellors were taught to inform reception that there was a `Code Six’. Montgomery had got the idea after witnessing an incident at his local supermarket, where store detectives had spotted a man shoplifting. There was a request on the tannoy for `Customer Service Eleven’ which, Montgomery explained, was the cue for all the biggest men from the meat counter to sprint out, wrestle the suspect to the ground, and sit on him.

But the majority of Resolve’s clients, especially the telephone callers, were bored, drunk or vengeful rather than clinically disturbed. Daniel, being single, frequently found himself working the phone lines at night. Often, as he struggled past the morning commuters, down into Tottenham Court Road tube station, and back to his small flat in a tower block by Clapham Junction overground station, it would occur to him that he had far more to complain about than most of his callers.

Most, but not all. One of his regulars was Richard, a young pianist from Oxford, who had been pushed backwards over the balcony at the Caf” Fitzrovia in London by his male lover. Richard fell twenty feet into the main restaurant area, where his landing was broken by a twenty-one-year-old woman who was celebrating her forthcoming wedding. Sitting with her, and not injured, were her fianc”, his mother, and her parents.

`Her name was Sara Allen,’ Richard told him. `She broke her back, and fractured her skull, and she died in hospital two days later.’

Richard, who was in tears, had told him the story at least a dozen times before, and there were no signs that repetition was therapeutic. The only shift in the emotional balance since his first call, Daniel noticed, was that now their conversations were bringing him dangerously close to tears as well.

`She’s dead,’ Richard told him, as he always did. `I had two broken legs and a fractured cheekbone, and I was out of hospital in three weeks.’

`Every day,’ Daniel said to him, sounding, to his horror, like some MGM padre, `is a new day.’

`Every day,’ Richard said, `when I wake up, the memory of it comes to me, as if it was the first time. There’s not a day goes by when I don’t wish she’d been anywhere on earth but in that chair.’

`Because,’ said Daniel, quietly, `she’d still be here.’

`No,’ said Richard. `Because I wouldn’t.’

So it was hardly surprising if occasionally, in the bar after a day shift, Daniel would betray the confidences of Nigel, a fifty-two-year-old sexual compulsive with manic-depressive tendencies who had recently been experimenting with Viagra. `He’s the last person in the world,’ Daniel told his colleagues, `who needs it. It’s like tossing kerosene into a live volcano.’

`I took it,’ Nigel had told him, `then I sat on my own, downstairs in the kitchen for about half an hour with my Cindy Crawford pictures. Nothing. So I made a cup of tea and went out to lock up the greenhouse. When I came in again I started to read the share prices in the Sunday Telegraph and – berdoing!’

But it wasn’t Nigel or Elliot, or even Sara Allen that had uniquely marked the name of Maple Street in Daniel’s mind. Those memories he could live with. It was something else. It was in Maple Street, one evening just after Easter, that he met Laura.

The first thing he noticed about her were her eyes, which were – though it was not a category of iris allowed by the passport office – jet black. Otherwise she was an unlikely femme fatale, with shoulder-length, straight black hair and an underdeveloped, boyish figure that had caused her agonies in her adolescence at school, when she still cared what anyone thought of her. She smoked heavily, and she had the obstinate strength and the accent of her American father. `Impervious’ would have been a good word for her; nothing Daniel, or anybody else, ever said or did would ruffle her aberrant view of the world. She went off in his life like a bomb.

He met her in the Caf” Leon, a wine bar three doors up from Resolve, on a Monday at the beginning of April, a few weeks before his final assessments began. Daniel had gone down there around eight in the evening with a group of ten or so, mainly recent recruits to Resolve like himself. She was on the other side of the table with her boyfriend Robin, who acted as a consultant to the company. He was a practising psychotherapist – a real one, who helped detectives construct profiles of suspects. Robin spoke, with a quiet authority, about his police work. The great weakness about hardened criminal organisations, he said, was that their behaviour patterns were, to a certain extent, predictable.

`There are some professions, such as that of gangster,’ he said, `which naturally attract the psychopath. Fighter pilots,’ he added, `not airline pilots. Deep sea divers. Mercenaries. Coal miners …’

By this point, Daniel wasn’t listening.

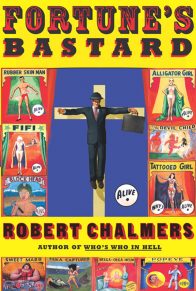

Copyright ” 2002 by Robert Chalmers. Reprinted with permission from Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.