All it had was empty rooms, and me. And it wasn’t even my house. None of this mattered to her. She was looking for something else entirely, but I didn’t know it then; I only heard her as she came.

I’d settled for the night in the corner of what used to be the front bedroom, tucked myself in next to the alcove where it was warmer. The girl stopped at the doorway, then went over to the fireplace, holding her hands out for a minute in front of the heat. I thought maybe she hadn’t seen me; unless you were looking, I’d be easy to miss. I watched her slip across to the far end of the room. On the wall, her shadow was giant. From the corner, she studied me. The fire died down and I kept still. I wasn’t afraid, then; she could please herself, is what I thought. She’s only a girl, and not the first I’d seen on the streets. She did nothing for a while, just stood there. The wind was butting at the glass, but she didn’t shift. She was black in the darkness, and when she finally moved, it was a creeping thing she did: slowly, slowly, feeling her way over to where I lay. I thought she wouldn’t take any notice of me. I was wrong. I closed my eyes and kept still, like a mouse in the shadow of a cat.

The next thing I knew, her hands were on my face. I couldn’t look; I was playing dead, and she was so quick, running her fingers over my head, under my chin, along my neck.

And just as quick, she was away, jumping the treads at the bottom of the stairs, shrieking like a firework as she landed. I could feel my heart, like a bird, trapped in its cage, banging at my ribs. She wasn’t out. She was in the hall. She was moving through the back of the house. A shunt of sash, a blast of air: she was gone.

I stayed quite still. I think I was in shock. The day came up and showed me an empty room, a dead fire, a blue morning. All that I had left was the plastic bag with the face on it. I kept it in my inside pocket, next to my heart. She didn’t get that.

It’s only another loss; it’s not as if I’ve been harmed. I’d like to say she didn’t touch a hair on my head, but that would be a lie.

everything

I’ll take my time. It won’t do to miss things out. I’m sure I’d never seen her before: names won’t stay with me, but a face is my prisoner for life. I’d been living in the house for a good while. To be straight, I was living in just the upstairs room. It wasn’t always empty either; people came and went. I didn’t mind them and they didn’t mind me, and sometimes we knew each other. It used to be a shop, on a parade that was full of shops: Arlott’s the butcher, a bakery with its bicycle outside, a post office run by two old women who looked like twins; and this one on the end, which was a fancy cobbler’s. It had a sign painted in gold across the window: Hewitt’s Shoe Repairs and Fittings, with Bespoke picked out in smaller lettering underneath. The front was already boarded up when I came back, but the words were still there in the glass; you could see them, etched backwards, from the inside. I knew what it said anyway: I had visited this place when I was a girl. Hewitt led me into the back room, for a fitting, he said. Called it the Personal Touch. He had Devices, Methods, cunning hands.

The only window that wasn’t boarded up was the upstairs bedroom at the front, which is why I liked it. At night, you could look out at the blackness, see the stars. All the other sleepers stayed downstairs. They were just lads, really, lads with nowhere else to go. Lads afraid of ghosts. They said they could hear Hewitt bumping about, and one of them told me he saw him on the top landing, holding an iron bar above his head. Describe him then, I said, and the lad puffed himself out big and made a roar. Well, that wasn’t Hewitt; he was small, with a face like a ventriloquist’s dummy and a voice to fit, as if he’d got a tiny man trapped in his throat. So perhaps the lads were just trying to scare me off. They couldn’t know, could they, that Hewitt’s ghost wouldn’t frighten me one bit; it wouldn’t hurt me to think of his restless spirit. But I don’t like to think of Hewitt at all, if I’m true – not of him, or his time. I used to call it Before, like BC but without the Christ. Then I stopped calling it anything, and the past didn’t trouble me. This is the only time there is, I used to tell myself: there never was a Before. I’d got to thinking it was a fact. That was how I managed.

It’s not as if I was a derelict. I knew what I wasn’t, even if I didn’t know what I used to be. And I can remember things if I’m pushed. The Sisters from the House had found me a place. Let me out the side door and put me on my way. Run by nuns, they said, as if I hadn’t had enough of them already. I might have gone there, but I knew what they would want; they would want to cleanse me. Start with my soul, I’d say, but they wanted me clean from the outside in, pulling at my clothes like a clutch of thieves. They said I was an Object. An Object who had fleas. They said cleanliness is next to godliness. Well, I know that’s a lie. I wasn’t having that, lying nuns and thieving to boot. And it was me who was supposed to be the thief, me the liar.

When the Sisters decided I could obey the rules, they let me go. I took my case and walked. And when I found Hewitt’s place again, I stayed. They’d laugh at me now, the nuns; now that I’ve lost everything to a sly girl in the dark.

The day she came was ordinary. Sometimes there’s an event, like a snow, or a funfair, or Christmas lights going on in the city, and it reminds you how the year rolls over.

But mostly there’s no edge, just tumbling days, which is how I like it. I have a routine which is rarely spoiled; it stops me having to think. I go down to the open market in the morning to fetch boxes. I like the colours on the fruit and veg stalls, and the men there never change. The stalls are on one side, and a row of shops on the other with girls’ dresses – bits of rag more like – on dummies in the windows. They wear smug, eyeless smiles, expensive clothes; some of them are bald, some naked. They’ve nearly all got bare feet. I stay on the stalls side.

They call it The Walk, this street, and it is like a place to promenade, with the castle on the mound, and the market with its awnings, and the two grey churches crouched like dogs on either side. At the back of the market is the city hall, which I’ve been to often enough, and round the back of that is the police station. I’ve been there too, if I’m true.

No, there was nothing exceptional to the day, unless you count the pumpkins. All the stalls were orange with them, piled up on each other, glowing like a monstrous hatch. They were for cutting into faces. Some of the stallholders had made their own lanterns and hung them over the displays, grinning and twirling in the wind. The thought of them at night-time, lit up and jeering, was horrible to me. I was lucky with the firewood. There were lots of crates, on account of all the pumpkins. I found some broken bits, and the boy on the flower stall gave me a bin liner to carry them in.

There was a panicky sort of wind about, swirling everything up from the gutter and blowing dirt in your face. Eyes full of grit; with my case and the bin liner, I was preoccupied with weather, the fret on the air. I wasn’t stopping; not stopping even to thank the boy on the flower stall, not stopping for anything. I was wearing my silver coat. Precisely, if I’m true, I was wearing my silver coat with the plastic bag in the inside pocket, and the shoes I’d got from the Salvation Army the week before. I had my case with me. I always took my case. It was all so ordinary, but these things seem important now: the pumpkins grinning, me carrying the sack, wheeling my case along, not stopping, wearing my silver. As if to alter just one thing would have brought about a different end.

I forgot myself in all that, worrying about the wind and would it bring rain, and would my hair get wet. That was my worry: would my hair get wet. I feared the rain, when it came. I had a routine; getting soaked through was not part of it.

I planned to make a fire when I got back, straight away, to dry things out. Not drying things makes them smell. I do not smell. I do not want things that smell.

When I settled in Hewitt’s, there was plenty to tear, lots of things to burn. He’d left the storeroom piled with boxes full of unclaimed shoes, and row upon row of insoles sliding on each other like dead fish. Under the counter at the front of the shop he kept thick wedges of tissue paper, leather-bound books of accounts. There was the open cabinet near the door, the kind that people have in their houses to show off their china and glass. Hewitt’s cabinet was full of carved wooden feet – lasts in an assortment of sizes. Each had its own brass plate with a name etched on it. They looked like museum pieces now.

Everything was torn and burnt, in the end. The boxes went first, then the counter, then the shelves, and then the cabinet itself. At night I’d hear the lads downstairs, smashing and cracking and breaking the wood into pieces small enough to fit in the hearth. Sometimes one of them would call me down. Robin, he said his name was. He was the only one that didn’t have a dog.

I’m wary of commitment, that’s my trouble, he’d say, which would make the rest of them laugh. He was a nice boy, too thin though, always near the fire, always toasting something. The others would joke about my boyfriend the ghost, but I’d put up with it, and Robin would give them a look, or change the subject. They weren’t to know, were they, and I was thankful for the warmth. How could they understand the twists a life could have? They were so young. And so sure of themselves. They could talk all night; gossip and dreams and wishful thinking – what they’d do if they won the lottery. Robin would always say it would never change him, and one of the others would laugh and say, yeah, sell your granny for a fiver, you would.

Now I have to think about it, I consider another thing: I liked to watch it all being ripped to bits, the lads tearing out the pages from the ledgers, balling the paper up in their hands and throwing it in the grate, or twizzling a long strip in their fingers and using it to light their cigarettes. The account sheets looked like a musical score, with its lines and notations; the owing and debt carefully registered in old brown ink. It was satisfying to see Hewitt’s neat little figures go up the chimney, watch the flames lick around his writing, see him burn in hell. But I never let on. I never let on how much I enjoyed it, not even to myself.

When the ledgers were gone, only the lasts were left. No one liked to destroy something that looked so human, but after a while, they went too. Cold alters your thinking: they were only made of wood. We’d sit and watch them go black and blacker, then burst into flames, like the foot of a mythical god. I kept one back, just for me. It was divine to hold, small and perfectly smooth. It had a name cut into the brass plate. I put it in my case, for safe keeping.

The wind was bringing in winter. The boy on the flower stall complained about it, stamping his feet like a horse in a paddock. He was breathing out smoke, or frozen air. He mentioned the wind. The market boys always went on about it, blowing from the east; straight off the Steppes, they’d say. That’s why I bedded down in the alcove that night; the wind was banging at the front window, coming down the chimney in gulps.

Once Hewitt’s fixtures were burnt, there was nothing left. By then, I was mostly on my own. That was summer just gone; people who hadn’t already moved on were finding other places to go. I don’t know where they went. Robin told me of the refuge on Bethel Street being reopened, and a new hostel down near Riverside. He had a plan, he said, some halfway scheme.

Halfway’s better than no way, he said, Might as well give it a try.

I didn’t have a plan. Not a thought to go anywhere else. No one invited me when they went, and that suited me well. I think I thought I was immune. Precisely, if I’m true, I didn’t think at all; it was my routine, to not think about anything, just to go on. The nights drew in.

I took the sack and my case upstairs, and made my way down to the back of the house. It had been nailed up from the outside with sheet metal, but one of the lads had pulled the board off the window, so you could get into the house from the back, if you had a mind to. I didn’t see the point, when there was a front door to use. They liked it though, this through-way, and it didn’t bother me. I had to climb through the window to get into the yard. There’s a shed in the corner where Hewitt used to store coal. It was all gone, the coal, I knew it would be, but I found some slack and loose pieces, cupped the dust in my hands and went back upstairs. It needed three trips, climbing in and out the window like Buster Keaton. I’m not infirm. I am my grandfather’s age. I left a trail of shimmer all through the hall and up to the top, like a great snail. Making the fire took most of the light out of the day. By the time it was properly going, the sky outside was black.

Apart from my bedding, the room was empty. I spread my coat out in front of the fire. Flames turned the silver to gold. My case with everything in it was at my side. My plastic bag was in my pocket. My hair, of course, was on my head, drying nicely. Everything was normal.

I might have looked out of the window then; I might have seen her. But I was preoccupied with the small things: staying dry, keeping warm, keeping to my routine. A step further back into the day, and I can almost believe that I would have passed the girl on the street. Perhaps I even looked at her. I would have wondered, wouldn’t I, what she was up to here, on The Parade, where no one goes shopping and no children play. I am not unobservant. Perhaps she didn’t come until late. Or she might have been waiting for it to get dark, waiting for her chance.

But I didn’t look back into the day; not this or any other. I never looked back and I never looked on, and if I told myself anything, if a memory came creeping into my head, or if I found myself out of a dream where I was a girl again and my life was flapping out in front of me like a flag, I’d say, That wasn’t your life, now, that belonged to someone else. That was just before.

My plan was just to go on as I was going on, each day the same until the end. I will consider it, now I’m forced: there was no plan. I kept out of the way. I was nothing much.

She took it all. I can picture her watching my face, kneeling down at my side. Her fingers were cold. She must have been looking for jewellery; why else put her hands on me? She could have just lifted my case, and left. She didn’t have to touch me. The girl put her fingers on me, the girl took everything I own. Now there’s some accounting to do. Her hair was red as rust: Telltale. I used to have red hair, when I was a girl.

part one: before

one

I’ve got to go and live with my grandfather. I don’t know him, and my father won’t be coming with me, but there’s nothing to be done. It’s been decided.

Needs must, Pats, my father says. It’s a mystery to me. He doesn’t explain the words, and I’m not allowed to question. I’m going to live with an old man that I don’t know and my father can’t abide. He used to call him That Old Devil, but now that needs must, my father doesn’t call him anything at all. I’ve never met the devil, but I’ve seen his face.

Under the stairs in the pantry there was a carton which I wasn’t allowed to touch, sitting alongside other things that weren’t touchable, like the Vim and my father’s shoe polish. The carton had got lye inside, which is poison. There was a picture of the devil on the outside, to prove it. He had a red face, red hair, pointed teeth, and a tail going up in a loop, sharp as a serving fork. He didn’t look at all like my grandfather. My mother kept a photograph of him in a silver frame on the table next to her bottle of Wincarnis. I wasn’t allowed to touch that either. The picture was in black and white. When my mother did her hair, or sometimes when she slept, I would sit on the stool by her bed and stare at him, and think about the devil inside. I reasoned that his face could be red in real life, and he wasn’t smiling, so he could easily have pointed teeth. In the photograph, he looked uncomfortable. That would be the tail, doing that: he’d be sitting on it. In his little round eyeglasses, I could see someone else standing a long way off. Two someone elses, one in each eye, holding a bright thing in the air above their heads. I imagined this was a cross of fire to ward off my grandfather, sitting there having his photograph taken. I wanted to compare him with the devil on the box of lye, put the pictures side by side, see if they made a pair, but I couldn’t get them together in the same room if they were not to be touched. I tried to memorize them instead: the devil was easy, his wide grin and his hair so red; but my grandfather – he just looked like any old man, any plain old man in the world. And then one day I saw for myself how not like the devil he was.

We lived near the lanes, in Bath House Yard. We’d always been there, so I knew all the faces round about: next door to us was a tiny woman called Mrs Moon, with no husband and four children all alike; and in the corner lived two brothers with a bulldog that bit your legs when you ran past. Across the yard was the knife-grinder. He did the rounds on his bike. When he came home, he’d leave it in the yard outside his window. There were cloths tied to the back, and a basket full of tools on the front. The dog never messed with him. He preferred the butcher, who lived in the rooms on top of us. I didn’t know the butcher’s name, and hardly saw him in the daytime, but I heard him, moving above my head in the morning, singing when he came home at night. Sometimes I looked out of my window to watch him staggering up the steps; he’d be hanging on to the railing like a man at sea, with the bulldog snipping at his boots, waiting for him to slip. It was easy to slip on the steps; the whole yard-end was leaning one way, as if any minute it would run off through the gutter and down into the city. My father said it was because of the quarrying underneath. We lived on lime, he said. My mother said it was the ghosts that made things tilt. If anything happened in our house, she blamed it on the ghosts.

They made everything slant. Our front door turned out onto a path of cobbles made of flint. They looked like pigs’ knuckles laid out flat. Except they didn’t stay flat, they sloped, and when it rained, the water came in under the door. My father put up a low wall around our door to stop the water. Everyone in the yard admired it, but no one wanted one of their own.

My grandfather came to see us just after I’d started at school. According to my father, it was because I didn’t go often enough. In truth, I hardly went at all. My father came to collect me at the end of the first week, and found me sitting at the back of the room at a little table, just me on my own. While all the rest of the children were doing the alphabet, I was sticking felt animals on a board.

Call that learning? he asked the teacher, who could only say that the idea of learning was beyond some of us and it was nothing to be ashamed of.

She’ll not be shoved in a corner, my father said, To be forgotten.

After that, I didn’t go any more.

My grandfather paid a visit to Talk Some Sense into us. My father wasn’t worried, he said the Moon children never got any bother, did they, and anyway, he wanted me at home. It wasn’t as if I missed going to school. I liked to play in the yard. I’d join in Ring-a-Roses with Josie and Pip Moon, but if the bulldog was out and about, I’d sit on the butcher’s steps with my legs tucked underneath me. The day it all changed, I was doing just that.

A grey man came and stood at the wall. He had a hat in one hand and a piece of paper in the other. From where I was sitting, I could see the bald bit on the top of his head. He didn’t knock on the door, and he didn’t say anything, he just looked up at me. He reminded me of someone I knew.

You must be Lillian, he said, after a bit. He sounded friendly, but I couldn’t answer back. My father has told me I must not speak to strangers, and I wasn’t sure whether he counted. So I just looked at him. After a minute, he tried again.

You are Lillian, aren’t you?

It’s a trick question, I thought. Then I thought, Maybe I am a Lillian? And ran down to ask my father. I’m always getting stuck with my name, but Lillian at that moment sounded important, and the way he said it, the grey-faced man, made it more familiar than my other name, which my father always calls me by. It’s Patsy, my other name. My father thought it was important too. When I told him what the man said, he ran like a rat from the bedroom where my mother was kept, straight through the living room, jumping the wall out the front. I’d never seen him run like that, pushing me aside as if he was fleeing the devil, not rushing to greet him. When I followed, he shouted.

You stay there! Don’t move!

I stayed right where he pointed, on the doorstep, and watched as the two of them had words. The piece of paper was exchanged. My father turned without looking back and grabbed me by the hand. He had a fierce grip. He was squeezing my fingers in one hand and the piece of paper in the other. He slammed the door on the man, unfurled the paper in front of the fire and burnt it straight away.

Who was that man? I asked, watching the paper curling blue.

That was your grandad,

was all he said. Then he went in to my mother.

It was the first time I’d seen my grandfather in colour. He did look like the photograph. I wanted to ask him why he called me by the wrong name and why my father thinks he is the devil.

After a bit, I went into my mother’s room. She was lying on her side, with my father sitting on the stool next to the bed. They stopped talking and looked at me. The shutters were closed. I went to the window and opened them a crack to see out. The man who was my grandfather was still there, waiting, his hands hanging open at his sides. I thought he might wave, but if he saw me he didn’t show it. He was staring straight at the door, eyeing it just like the bulldog eyes me. I wanted to compare him to his picture. I glanced over to where my mother kept it, but the frame had been turned face down on the table.

Come away from there, Pats, said my father. But he’s still there!

Come away now, he said.

My mother gave a slow blink. She didn’t talk much, but she didn’t need to; her blinking said it all. It said she wasn’t going to get up and let him in, and I really shouldn’t ask questions at a time like this, or stand near the window like that, for everyone in the yard to see our business.

Why did he call me Lillian? I asked. No one spoke. I asked again.

My mother’s eyes were shut now. My father took a breath, I’ll tell you in a bit. Go and put the kettle on for your mam.

I did as I was told. But I knew if I looked out of the window I would see the man again, standing still and waiting like a dog.

Soon after that, the photograph of my grandfather disappeared entirely, and the frame was put on the sideboard with the glass cracked and nothing behind it but white. And then one morning, the frame was gone too. It was the time of the ghosts. It was the time, my father decided, that I should learn history.

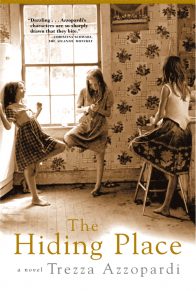

Copyright ” 2004 by Trezza Azzopardi. Reprinted with permission from Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.