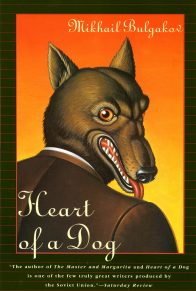

1. Bulgakov’s novel opens with a meeting between a poet and his editor, a loaded subject given the author’s experience with censors in the U.S.S.R. What is Berlioz’s quibble with Homeless’s poem? Is Berlioz’s act of commissioning the poem, then directing the poet to change it to suit his own tastes, unusual? How does Homeless take his editor’s criticisms, and what are his own thoughts on the freedom of expression?

2. Berlioz and Homeless have trouble placing the stranger who approaches them at Patriarch’s Ponds park, but they immediately peg him as a foreigner. What connotations does that word carry, especially in a closed society like the Soviet Union of the 1930s? What are the risks or dangers involved in meeting a foreigner? How does Berlioz try to establish his identity, and when does he start to realize that the stranger is not who they take him to be?

3. When the foreigner learns Berlioz and Homeless are atheists, he poses the age-old question of free will: “If there is no God, then, you might ask, who governs the life of men?” (p. 11) Which position is he arguing? Berlioz doesn’t have the chance to counter, but what are some possible objections to Woland’s view? In the novel’s world, does his very existence nullify these objections? What is the “seventh proof” referenced in the third chapter’s title?

4. What is Pilate’s state of mind as he begins to question the prisoner? In what ways does the prisoner surprise Pilate? Consider the parallels between this encounter and the one in the opening chapter. Are there any similarities between the prisoner and the foreign professor?

5. What are the prisoner’s offenses, and how does he respond to the accusations? What is Yehudah of Kerioth’s role in the arrest? Consider the ways in which storytelling and speech figure in each of the prisoner’s charges, as well as the consequences that these actions carry. Why is Bulgakov, as a Soviet writer, interested in exploring these themes?

6. Why does Pilate seem to sympathize with the prisoner? Why does he confirm the death sentence anyway? What is the High Priest’s role in the judgment? Where do he and Pilate differ, and why?

7. “Any visitor to Griboedov’s . . . immediately realized how well those lucky chosen ones—the members of MASSOLIT—were living” (p. 61). Why is life so good for MASSOLIT members? How do the Griboedov House amenities serve MASSOLIT’s stated function? How does Nastasya Nepremenova, alias Pilot George, explain the distribution of services among members (p. 64)?

8. How does Homeless describe Ryukhin, the poet who brings him to the psychiatric hospital? Why does this rant plunge Ryukhin into an episode of self-doubt? Are Homeless’s criticisms literary, political, or both?

9. Like many Muscovites of the 1930s, Variety Theater’s director Stepan (Styopa) Bogdanovich Likhodeyev resides in a communal apartment. Who are the other tenants, and how does Woland arrive there? What does he do with Styopa, and why? In what ways is Styopa’s sudden eviction a reflection—albeit an extreme one—of the politics of Moscow real estate that emerge later in the book?

10. Why does Ivan/Homeless remain in the psychiatric hospital? What is he trying to compose, and why does he find it difficult? Are Ivan’s attempts and frustrations unique to his situation, or are they common to the writing process?

11. Why is house chairman Nikanor Ivanovich so hotly pursued after news of Berlioz’s death spreads? What kind of bargain does he strike with Koroviev/Fagot, and on what grounds is he arrested?

12. What does Woland/Koroviev’s performace reveal about the audience, and why is the performance particularly subversive in 1930s Moscow? Who is most insistent on debunking the magic act, and what does Koroviev/Fagot expose instead?

13. Few novels introduce their protagonists as mental patients. What’s behind Bulgakov’s radical choice, and what sort of context has he given the reader to evaluate our hero? What’s your impression of the Master and of his beloved?

14. What are the parallels between the Master’s experiences and Ivan’s? Who are Latunsky, Ariman, and Lavrovich? What accusations do they make against the Master, and what are the consequences?

15. Alcoholism has plagued Russian society for generations, and drunkenness comes up frequently in the novel as an explanation for odd behavior. So why does Rimsky begin to doubt Varenukha’s account of Styopa’s booze-fueled escapade? What else does Rimsky begin to suspect, and what saves him from Varenukha?

16. Why is Matthu Levi tormented? What are his failures, if any? How does he arrive at the scene of the execution, and what does he conspire to do?

17. What do the visitors to apartment Number 50 have in common? How are their plans thwarted by Koroviev and his gang? Do they exercise any control over their destiny?

18. “It can be said with absolute assurance that many women would have given anything to exchange their lot with Margarita Nikolaevna” (p. 235). What kind of life does Margarita lead? How is her existence enviable, and in what ways is it miserable?

19. Why does Margarita decide to trust the stranger she encounters while watching Berlioz’s funeral procession? What sort of bargain is she striking, and does she understand the implications of her actions?

20. Consider the different ways—physical and psychological—in which Azazello’s cream transforms Margarita. What kind of witch is she? What does she do with her newfound powers, and where does she draw the line?

21. When Margarita arrives on Sadovaya, Koroviev compares using the fifth dimension to expand apartment Number 50 to complex but common real estate transactions in Moscow, where apartments couldn’t be owned but could be swapped endlessly to gain space or change location (p. 268). How well-suited are Satan and his retinue to navigating the bizarre Soviet landscape? What is Bulgakov implying by plunking the devil down in Moscow?

22. Why has Margarita been chosen to serve as hostess for Satan’s ball? What responsibilities is she assuming, and what does she think will be her reward? Is it an advantageous trade-off? Is it possible to win when you’re striking a deal with the devil?

23. What is the common thread between the people in attendance at the ball, from the orchestra to the suffering Frieda? What is the purpose of the gathering, and what is Margarita’s role?

24. What does Margarita ask for her services, and why? How does Woland fulfill these requests? Who is Mogarych, and how did he come to live in the Master’s apartment?

25. What does the chief of secret police reveal to Pilate about Yehuda of Kerioth, and what does Pilate reveal to him? What are Pilate’s orders, and why is he so concerned with this matter? Does Aphranius succeed?

26. Why does Pilate want to meet Matthu Levi, and how does his conversation with Yeshua’s disciple compare to the one he’d had with Yeshua? What are the power dynamics of this meeting? What does Pilate offer Matthu Levi, and why?

27. Why does Matthu Levi come to see Woland, and what do these two think of each other? Who decides the Master’s fate? What is Woland’s solution and why is it “so much better” than the alternatives, as Margarita suggests? What statement is Bulgakov making about the possibilities of creative life in Soviet Russia?

28. Where does Woland take Master and Margarita, and why? What does he offer the Master? Why are the paths different, and is one better than the other?

29. What does the investigating committee conclude about the odd events that took place in Moscow during Woland’s visit? What becomes of the people who encountered him? What becomes of the poet Homeless?