News Room

- Home

- News Room

- Author Interviews

- A Q&A with Anton...

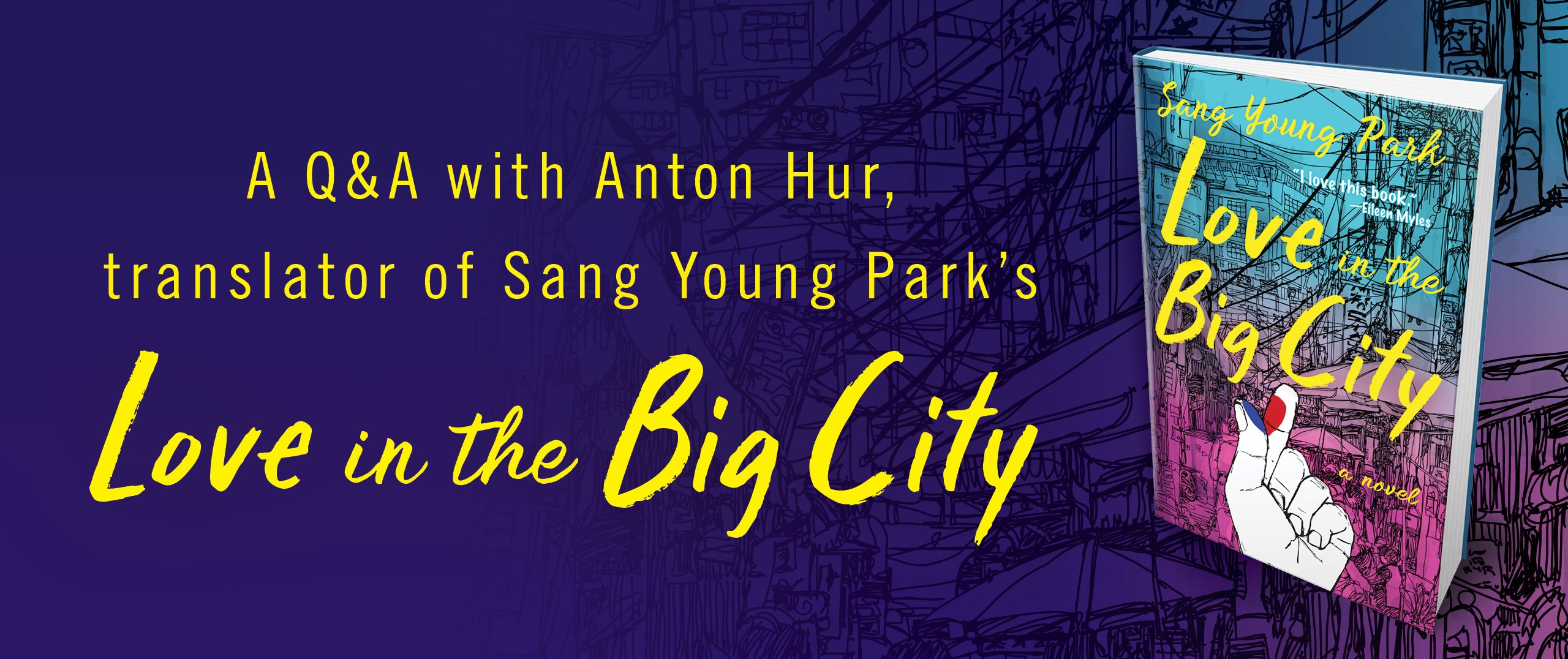

This fall, we couldn’t be more excited to be publishing Love in the Big City, South Korean writer Sang Young Park’s funny, transporting, surprising, and poignant novel about a young gay man searching for happiness in the lonely city of Seoul, in a fresh, neon-vivid translation by Anton Hur. As advance copies began making the rounds, Grove intern Jenny Choi read the book twice — once in the original Korean, and once in Hur’s masterful translation — and prepared a series of questions the translator was kind enough to answer. The resulting conversation is urgent, informative, and, as you’ll see below, more than a little entertaining. Enjoy — and don’t forget to check out Love in the Big City, on sale now!

JC: How did you come to know about Sang Young Park’s work before Love in the Big City?

AH: Literary magazines. I’ve known about Sang Young since his first published story, “Searching for Paris Hilton,” in Munhakdongne Quarterly, but it wasn’t until he published “The Tears of an Unknown Artist, or Zaytun Pasta” in Changbi Quarterly as a short story that I wanted to translate him. This was before he had published any of his books. I’ve talked to a lot of people who assumed Sang Young Park was “given” to me to translate by magical publishing people or whatever, but that is very far from the case. I very much found him on my own and went begging for the right to translate his work, doing a lot of work on spec because I believed in bringing Sang Young into translation. I was the one who sold his work to Tilted Axis Press, who then brought it to Grove Atlantic. I guess the magical publishing person is me.

Which character did you most look forward to translating into English, and which character did you find the most difficult or straightforward to translate?

As a translator, I don’t really think in terms of characters so much as narrative voice. I could hear Sang Young’s prose immediately in English, or at least my version of what he would sound like. I’m kind of not a fan of any of his characters to be honest, I’m a fan of the writing itself, of Sang Young Park’s writing. I can definitely recognize the different kinds of bad boyfriends in the story, as I was also once a twenty-something gay in Seoul. There were moments where I was practically screaming with recognition. But I didn’t find any characters difficult to translate, not even Young’s mother or his awful book editor boyfriend in the second section. Sang Young is such an honest writer, relentlessly honest if you will, that I know exactly what he means in every word of his text. He’s also effortlessly hilarious, which just brings everything up a notch in terms of fabulosity.

In a previous interview, you mentioned that Love in the Big City has a “Western sensibility in the language,” and in the Korean language edition, Park uses English loan words in place of Korean words (i.e. screen, table, bathtowel, to name a few). How did you transfer this dynamic into English?

The Korean language has a lot of Western loan words to begin with, so that’s not quite what I meant. I think Sang Young has what I jokingly call an Anglo-Saxon vibe in his prose, a kind of hyper-clear honesty tinged with the relief of self-deprecating irony. His style lends itself extremely well to English translation. There are other authors with whom the distance to traverse seems so overwhelming that I wonder at how it even occurs to their translators to translate them. For example, I don’t look at Han Kang and think, Wow, what an easy writer to translate! Deborah Smith is a much braver soul than I, and she’s done what is frankly a superhuman job. If Han Kang’s work resists translation, Sang Young’s invites it. His stories are very urbane, and there’s something cosmopolitan and transnational about cities. There was a big urban sensibility in Anglophone traditions for me to draw from, ranging from eighteenth-century newspaper columns to Candace Bushnell’s Sex and the City. It was very easy to place Love in the Big City in that tradition.

Because a translator acts as a bridge between cultures, I’m curious about what struck you as points of connection for Western readers of Love in the Big City as a queer work and as a Korean work of literature? What about these traits will attract a reader who might not speak Korean, know about Korean culture, or identify with the LGBT+ community?

When I read Hosam Aboul-Ela’s Domestications: American Empire, Literary Culture, and the Postcolonial Lens, it struck me that so many of the narratives in the West that depict queer life outside of the West are very white-centric. You have some white person, an English teacher or an American official, going to China or Eastern Europe and sleeping with the locals—that’s the plotline to many a queer novel or memoir written in the West and set in Africa or Asia. Meanwhile, there’s only one white person mentioned in all of Love in the Big City, and that’s Kylie Minogue (there’s also a French concierge with a speaking part but his race isn’t specified). I can’t even tell you how revolutionary it is to even read an Asian gay book where the Asian gay protagonist isn’t paired with a white partner. And that’s possible mostly because this is a work of translation. Whereas if a gay Asian writer wants to write a book like this in the West, a gay book with no speaking parts for white people in other words, they would have many obstacles to overcome. But that’s the extent of my thinking about what non-Korean or non-queer readers will think about this work. My belief as a lifelong reader is that if the voice is compelling, people will read the book no matter what. Readers want to be surprised that they like something new and different. And this book delivers on that front.

The range of stories you have decided to translate is quite varied, jumping from the quirky speculative fiction of Cursed Bunny (2021) to the melancholy wanderings of Ocean Vuong’s poetry which you’ll be translating into Korean later this year. As you decide what you want to translate, what characteristics in writing style, character, storyline, or premise draw you to a particular story, whether that’s in prose or poetry? Is there a specific kind of narrative or social commentary that you look for alongside who is writing the story?

This is one of those questions that you hope someone will ask you but never comes up because people assume translators are completely passive functionaries or mindless robots that just do the job they’re given, and to be fair, some translators are like that. Everyone has their own way of doing things, and mine happens to be that translators are a privileged kind of reader that can change the way a reading audience thinks about things like nations and neo-liberalism and systemic injustice. Often translators can and should really think about what they want to translate, how they want to translate it, and about which discourse their translation could reframe or impact. As for me, I am interested in subverting the white-supremacist and Korean-nationalist narratives surrounding Korean literature and Korea itself, choosing works that amplify the voices of non-men, queers, and other social minorities, not only because they have compelling stories to tell but also because these writers happen to have beautiful literary voices. An older Korean translator once mocked me for jumping on some “queer trend” bandwagon, and this is the default that I have to deal with on a daily basis: my very existence as a queer person being reduced to a “trend.” Unfortunately for him, I’m still here, and very caffeinated, and it is a brand-new day.

Grove Atlantic is delighted to acknowledge the support of the Literary Translation Institute of Korea in the production of this interview.