In April, the season in my part of the world officially opens–and the season of preparations unofficially closes.

In February, I went to one of those shows–crammed with a fly fisher’s candies–and bought four years’ worth of sweets I’ll never use. Then I arranged my 10,473 flies yet again–Eastern, early, mid, and late, Western, bass, bluegill, Northern saltwater, tarpon (will I ever go again?), spring creek, pike, and stuff-for-particularly-dumb-fish-of-many-species. I threw out a hundred, gave another hundred or so to Sandy, who will be fishing the East more this year. I suspect I have enough left. Maybe.

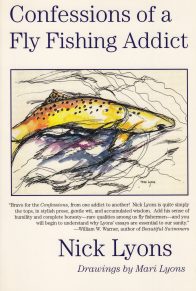

It wasn’t such hard work. Each fly has a life all its own, with virtues that have proved their worth a hundred times to me–the sparkle shuck, the thorax winging, a certain color to the body and hackle–or flaws that make all other efforts futile. I am a fly addict and can pick and sort and chuck out flies for a week, nonstop, and then it’s time to go on to my nineteen rods and thirteen reels, numbers down substantially because I’m always giving stuff away or trying to trade up.

This rarefication of our fly-fishing lives goes on, for better or worse, willy-nilly, for as long as we fish. It is flagrantly arbitrary, for a brilliant rod to one of us is a club to another–but we persist because of an absolute belief in our pursuit of the one good, true, and beautiful stick. My old friend Frank Mele, who died this past winter, searched endlessly for the perfect fly rod, but was too wise to settle for merely one–any more than he could ever settle for a single, perfect blue dun neck. Each neck had a luminous, evanescent color all its own, its own strength of hackle fibers, its own good and proper value for fly tying. He had fifty necks, each slightly different, as all blue dun–and all bamboo fly rods–can be.

The rarefication is an activity worth the doing. It takes with it a certain set of preferences for certain kinds of fishing experiences. At one time any fishing would satisfy me; I could fish all day with bait, lure, or fly, in almost any kind of water. I would fish any time of day, anywhere. With a full life and a lot of river under my waders, I find I just don’t do that anymore. For one thing, I’ve learned this and that, and I’m less interested in fishing a Catskill river when the water is still forty-six degrees. I prefer to see a few flies on the water. And if it’s early May, I’m inclined to think that midday and early afternoon will be best, just as I’ll fish mornings and at dusk in the East when the summer heat has started.

You can’t turn back. You’ve been in a good number of fishing situations, you’ve done a good deal, and you make a few choices. Sometimes I think that one of these days I’ll rarefy my fly-fishing life flat down to bass-bugging on smallish ponds. I can’t conceive of getting enough of that kind of fishing–but that may be because I’ve done too little of it.

A few well-worn fly lines needed to be replaced this year, reels cleaned, the tip top that mysteriously broke off in Montana replaced. I bought new waders and a fresh supply of leader tippet spools, which I change every year, and I sewed the two rips in my twenty-one-year-old vest. Why, I don’t know, but I treated myself to a fourth pocket knife.

And then suddenly a new season started and I thought of Rilke’s little poem about the spring having come again and the earth, like a little child, knowing many poems by heart. Along with the earth’s green recollections of buds and sprouts, I began to remember too–a full fifty springs now, stretching back to my earlier days of fishing the East Branch of the Croton River on Opening Day with my friend Mort, when the rivers were always full of surprise and wonder. One year, improbably, I took a nineteen- and then a twenty-four-inch brown, both hook-jawed, both from the same pool on the Ten Mile River. On another, Tony almost got swept away in a heavy spring flood; now he’s thirty-five, well over six feet, and quite big enough to save me from floods and hurricanes.

One day recently I tramped the muddy banks of a river I’d fished a couple dozen times in my youth. Here and there, remnants of ice and snow were tucked into cool, shady comers of the hillside. The earth had not yet remembered its buds or skunk cabbage shoots. The water was too cold; the air still did not have that hint of warmth that says “flies.” I thought of a dozen friends I’d once fished the river with, now dead or in other parts of the world. Several were retired and did nothing but fish and play golf; their professional lives were over. One had given up fishing. I’d argued with another, Mike was dead, and I had to fight some days to remember his stories, the particular way he shook hands, smiled, cast a fly. The years had passed much too quickly and I couldn’t even remember certain sections of the river; they were quite new to me–changed, no doubt, by floods.

Two weeks later, standing in a familiar run, I saw out of the corner of my eye a break on the surface. Looking closely, my head tilted to the surface, I could see a few Hendrickson shucks floating by, and a moment later, in the sky, I could see the reddish flies fluttering upward or aslant, to the trees. The swallows had seen them too and began their aerial dance above me, pausing just for a second to take one of the fleeting mayflies. Then there were a couple of fish rising, and I stood still for a moment, remembering, feeling quite happy with the sight. The river was coming alive, as I had seen rivers come alive a thousand times before. There was a spark of light on the surface, the bird sounds, the circles on the surface, the swooping birds. I tucked my rod under my arm, fetched out a box of early-season flies, found a Red Quill, and soon had my first fish of the new year. It was a bright brown, icy in my hands, not quite ten inches.

It is such a happy sight, the slight curl of a rising fish to your fly, after you have watched it float twenty times over a patch of water no more than two feet square, where you saw a fish come up. It is especially nice when it is the first trout of the season, for now, at their proper times–barring floods or too much cold or too much heat–all the Eastern hatches will start, in the tight schedule that makes April through June so irresistible.

There are places in the world where the season never ends, where you can fish throughout the year. Ted Leeson writes of such a place, his Oregon, in The Habit of Rivers; and others extend their fishing year by travel either south, southwest, or to the antipodes, Chile, Argentina. I hear the reports and I hear the sounds of pleasure in the voices. The fishing was different but Superb. Bill caught a ten-pound bonefish in Belize, George a twelve-pound rainbow in a spring creek in South America. There are photographs to prove everything. It all sounds like fine sport. The photographs don’t lie.

But more and more, I am framed by the Eastern season. When it ends, as late as October, I open my fish closet, pile in all the paraphernalia I’ve been messing around with since April, and close up shop for the year. I have other matters to attend to, other lives. And so everything sits until the dead of winter, when, by chance, I notice that there are a few less than one hundred days until April. “It’s time to give serious thought to your tackle,” Frank used to write me, and I always did and still do, thinking all the time, with increasing intensity, of the day when the first flies come, the true beginning of a fly fisher’s spring.