A generous fish … he also has seasons. –Izaak Walton

There is a rhythm to the angler’s life and a rhythm to his year.

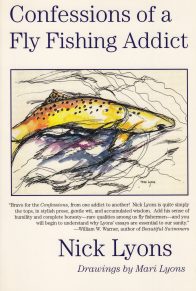

If, as Father Walton says, “angling is somewhat like poetry, men are to be born so,” then most anglers, like myself, will have begun at an age before memory–with stout cord, bamboo pole, long, level leader, bait hook, and worm. Others, who come to it late, often have the sensation of having found a deep and abiding love, there all the while, like fire in the straw, that required only the proper wind to fan it forth. So it is with a talent, a genius even, for music, painting, writing; so it is, especially, with trout fishing–which “may be said to be so like the Mathematics that it can never be fully learnt.”

There is, or should be, a rhythmic evolution to the fisherman’s life (there is so little rhythm today in so many lives).

At first glance it may seem merely that from barefoot boy with garden hackle to fly fisherman with all the delicious paraphernalia that makes trout fishing a consummate ritual, an enticing and inexhaustible mystery, a perpetual delight. But the evolution runs deeper, and incorporates at least at one level an increasing respect for the “event” of fishing (I would not even call it “sport”) and of nature, and a diminishing of much necessary interest in the fat creel.

But while the man evolves–and it is the trouter, quite as much as the trout, that concerns me–each year has its own rhythm. The season begins in the dark brooding of winter, brightened by innumerable memories and preparatory tasks; it bursts out with raw action in April, rough-hewn and chill; it is filled with infinite variety and constant expectation and change throughout midspring; in June it reaches its rich culmination in the ecstatic major hatches; in summer it is sparer, more demanding, more leisurely, more philosophic; and in autumn, the season of “mellow fruitfulness,” it is ripe and fulfilled.

And then it all begins again. And again.

I am a lover of angling, an aficionado–even an addict. My experiences on the streams have been intense and varied, and they have been compounded by the countless times I have relived them in my imagination. Like most fishermen, I have an abnormal imagination–or, more bluntly, I have been known to lie through my teeth. Perhaps it comes “with the territory.” Though I have been rigorous with myself in this book, some parts of it may still seem unbelievable. Believe them. By now I do. And why quibble? For this is man’s play, angling, and as the world becomes more and more desperate, I further respect its values as a tonic and as an antidote–on the stream and in the imagination–and as a virtue in itself.

These then are the confessions of an angling addict–an addict with a “rage for order,” a penchant for stretchers, and a quiet desire to allow the seasons to live through him and to instruct him.

Chapter Two: WINTER DREAMS AND WAKENING

The gods do not deduct from man’s allotted span the hours spent in fishing. –Babylonian Proverb

When do I angle?

Always.

Angling is always in season for me. In all seasons I fish or think fish; each season makes its unique contribution, and there is no season of the year when I am not angling. If indeed the gods do not deduct, then surely I will be a Struldbrug.

Yet sometimes in October I do not think angling. The lawful season has recently ended, I have neglected my far too numerous affairs grossly, my four children have begun school and are already cutting up, my wife trots out her winter repair list. It is a busy, mindless time.

But it is good that my secret trouting life lie fallow–after one season, before another. I welcome the rest. Sometimes this period in October lasts as long as seven or even eight days.

But by late October, never later than the twenty-third or twenty-fourth, the new season commences–humbly perhaps, but then there it is.

Perhaps the office calendar will inaugurate the new year this year. Casually I may, on a blustery late-October afternoon, notice that there are only sixty-eight days left to the year: which means since the next is not a leap year, that there are exactly one hundred and fifty-eight days left until Opening Day. I have long since tabulated the exact ninety days from January first until April first. It is not the sort of fact one forgets.

Or a catalog may arrive from one of the scores of mail-order houses that have me on their lists. I leave it on the corner of my desk for a day, two days, a full business week, and then one lunch hour chance to ruffle through its pages, looking at the fine bamboo rods with hallowed names like Orvis, Pezon et Michel, Payne, the Hardy and Farlow reels, the latest promises in fly lines, the interminable lists of flies, the sporting clothes.

Yes, perhaps this year I shall buy me a Pezon et Michel instead of that tweedy suit my wife assures me I need, or a pair of russet suede brogues with cleated heels and fine felt soles.

In my mind I buy the rod and receive it in the long oblong wooden box, unhouse it for the first time, flex it carefully in my living room. Then I am on the Willowemoc or the West Branch and I thread the line and affix the fly and the line is sailing out behind me and then looping frontward, and then it lies down softly and leader-straight on the water, inches from the steadily opening circles of a good brown steadily rising.

Yes, there is every reason why I should buy a Pezon et Michel this year. And a pair of brogues.

Or perhaps one evening after I have lit the fire, my wife may be talking wisely about one of the supreme themes of art, love, shopping, or politics, and she will notice that I am not there.

“You’re not at all interested in what I have to say about Baroque interiors,” she says.

“You know I am, Mari. I couldn’t be more interested.”

“You didn’t hear a word I said.”

“Frankly, I was thinking of something else. Something rather important, as a matter of fact.”

My wife looks at me for a long time. She is an artist, finely trained and acutely sensitive to appearances. Then she says, with benign solicitude–for herself or me, I cannot tell–”But it’s only October.”

“My mind drifted,” I say.

“Not the Beaverkill! Already?”

“No. To be absolutely truthful, I was not on the Beaverkill.”

“The West Branch of the Croydon? Fishing with Horse Coachmen?”

“Croton. Hair Coachmen. Actually,” (I mumble) “actually, I was on the Schoharie, and it was the time of the Hendricksons, and …”

And then she knows and I know and soon all my four children–who know everything–know, and then the fever smokes, ignites, and begins to flame forth with frightening intensity.

I take every piece of equipment I own from my fishing closets. I unhouse and then wipe down my wispy Thomas and my study old Granger carefully. I check each guide for rust. I look for nicks in the finish. I line up the sections and note a slight set in the Thomas, which perhaps I can hang out by attaching to it one of my children’s blocks and suspending them from the shower rod. (My children watch–amused or frightened.) I rub dirt out of the reel seat of the Thomas. I take apart my Hardy reel and oil it lightly. I toss out frayed and rotted tippet spools. I sit with my Granger for a half hour and think of the fifteen-inch brown I took with it on the Amawalk, with a marabou streamer fished deep into a riffled pool the previous April.

From the bedroom my wife calls. I grumble unintelligibly and she calls again. I grumble again and continue my work: I rub clean the male ferrule of my Thomas and whistle into its mate.

Then I dump all the thousands of my flies into a shoe box, all of them, and begin plucking them out one by one and checking for rust or bent wings or bruised tails; I hone points, weed out defectives, relacquer a few frayed head knots, and then place the survivors into new containers. I have numberless plastic boxes and metal boxes and aluminum boxes–some tiny, some vest-pocket size, some huge storage boxes. Each year I arrange my flies differently, seeking the best logic for their placement. Is the Coachman more valuable next to the Adams? Will I use the Quill Gordon more next year? Should all the midge flies go together? Only three Hendricksons left. Strange. I’ll have to tie up a dozen. And some Red Quills. And four more No. 16 Hairwing Coachmen. And perhaps that parachute fly, in case I make the Battenkill with Frank.

There is little genuine custom in the world today, and this is a consummate ritual: the feel of a Payne rod, its difference in firm backbone from a Leonard or a parabolic Pezon et Michel; the feel of a particular felt or tweed hat; those suede brogues with cleated heels and fine felt soles; the magic words “Beaverkill,” “Willowemoc,” “Au Sable,” “Big Bend,” and “trout” itself; the tying and repairing; the familiar technical talk, the stories. Fishing is not for wealthy men but for dreamers.

Have I always had so serious a case? Practically. That is the safest answer I can give. Practically. I cannot remember a time when I was not tinkering with my equipment; I cannot remember a time when I did not think about fishing.

And each item of tackle is charged with memories, which return each winter in triumphant clarity out of the opaque past: a particular fly recalls a matched hatch on the translucent Little Beaverkill near Lew Beach; a nick in my Thomas recalls a disastrous Father’s Day weekend evening on the East Branch when I almost lost the rod and forfeited my married life. And the mangled handle on my Hardy reel summons that nightmarish fire that raged in on the crest of furious winds during the dead of winter, buffaloing up out of the stone church next door and doing its work quick and voracious as a fox on a chicken raid.

I remember the policeman’s light flicking through my little study. My fly-tying table–with all the hooks and hackles, threads, and bobbins–had been decimated. I had raced to the closet, its door seared through. With the borrowed flashlight I searched into the hollowed-out section of the wall. My vest, in which I had most of my working tackle, hung loosely from a wire hanger. It was almost burned away. On one side, several plastic boxes had been chewed through: the flies were all singed or destroyed; nothing could be saved there. Little items–like tippet spools, leader sink, fly dope, clippers, penlite, and extra leaders–could be replaced easily enough: they were all gone. My waders were a lump of melted rubber; my old wicker creel was a small black skeleton on a rear nail; an ancient felt hat was a mere bit of rag; several glass rods without cases had gone up; a fine old net that had always been there at the crucial moments was only a charred curved stick; and a whole shelf of storied angling knick-knacks had collapsed and lost itself in the wet, black debris on the floor. In a corner, the aluminum rod cases were roasted black (Frank Mele later got Jim Payne to check them out: they are no doubt the better for it). And in the debris I found the Hardy reel, its chamois case burned away, the fine floating line devoured, the plastic handle mutilated.

And every Carlisle hook I ever see–long and impractical–recalls my first trout, my first fishing lie.

My first angling experiences were in the lake that bordered the property my grandfather owned when the Laurel House in Haines Falls, New York, was his. At first no one gave me instruction or encouragement, I had no fishing buddies, and most adults in my world only attempted to dissuade me: they could only be considered the enemy.

It was a small, heavily padded lake, little larger than a pond, and it contained only perch, shiners, punkinseeds, and pickerel. No bass. No trout. Invariably I fished with a long cane pole, cork bobber, string or length of gut, and snelled hook. Worms were my standby, though after a huge pickerel swiped at a small shiner I was diddling with, I used shiners for bait also, and caught a good number of reputable pickerel. One went a full four pounds and nearly caused my Aunt Blanche to leap into the lake when, after a momentous tug, it flopped near her feet; she was wearing open sandals. She screeched and I leaped toward her–to protect my fish.

I also caught pickerel as they lay still in the quiet water below the dam and spillway. It was not beneath me to use devious methods; I was in those days cunning and resourceful and would lean far over the concrete dam to snare the pickerel with piano-wire loops. It took keen discipline to lower the wire at the end of a broomstick or willow sapling, down into the water behind the sticklike fish, slip it abruptly (or with impeccable slowness) forward to the gills, and yank.

After the water spilled over at the dam it formed several pools in which I sometimes caught small perch, and then it meandered through swamp and woods until it met a clear spring creek; together they formed a rather sizable stream, which washed over the famous Kaaterskill Falls behind the Laurel House and down into the awesome cleft.

Often I would hunt for crayfish, frogs, and newts, in one or another of the sections of the creek–and use them for such delightful purposes as frightening the deliciously frightenable little girls, some of whom were blood (if not spiritual) relations. One summer a comedian who later achieved some reputation as a double-talker elicited my aid in supplying him with small frogs and crayfish; it was the custom to have the cups turned down at the table settings in the huge dining room, and he would place my little creatures under the cups of those who would react most noticeably. They did. Chiefly, though, I released what I caught in a day or so, taking my best pleasure in the catching itself, in cupping my hand down quickly on a small stream frog, grasping a bullfrog firmly around its plump midsection, or trapping the elusive back-dancers as they scuttered from under upturned rocks in the creek bed.

Barefoot in the creek, I often saw small brightly colored fish no more than four inches long, darting here and there. Their spots–bright red and gold and purple–and their soft bodies intrigued me, but they were too difficult to catch and too small to be worth my time.

That is, until I saw the big one under the log in the long pool beneath a neglected wooden bridge far back in the woods. From his shape and coloration, the fish seemed to be of the same species, and was easily sixteen or seventeen inches long. It was my eighth summer, and that fish changed my life.

In August of that summer, one of the guests at the hotel was a trout fisherman named Dr. Hertz. He was a bald, burly, jovial man, well over six foot three, with kneecap difficulties that kept him from traveling very far by foot without severe pains. He was obviously an enthusiast: he had a whole car trunkful of fly-fishing gear and was, of course, immediately referred to me, the resident expert on matters piscatorial.

But he was an adult, so we at once had an incident between us: he refused, absolutely refused, to believe I had taken a four-pound pickerel from “that duck pond,” and when he did acknowledge the catch, his attitude was condescending, unconvinced.

I bristled. Wasn’t my word unimpeachable? Had I ever lied about what I caught? What reason would I have to lie?

Yet there was no evidence, since the cooks had dispatched the monster–and could not speak English. Nor could I find anyone at the hotel to verify the catch authoritatively. Aunt Blanche, when I recalled that fish to her in Dr. Hertz’s presence, only groaned “Ughhh!”–and thus lost my respect forever.

Bass there might be in that padded pond, the knowledgeable man assured me: pickerel, never. So we wasted a full week while I first supplied him with dozens of crayfish and he then fished them for bass. Naturally, he didn’t even catch a punkinseed.

But it was the stream–in which there were obviously no fish at all–that most intrigued him, and he frequently hobbled down to a convenient spot behind the hotel and scanned the water for long moments. “No reason why there shouldn’t be trout in it, boy,” he’d say. “Water’s like flowing crystal and there’s good stream life. See. See those flies coming off the water.”

I had to admit that, yes, I did see little bugs coming off the water, but they probably bit like the devil and were too tiny to use for bait anyway. How could you get them on the hook? About the presence of trout–whatever they might be–I was not convinced.

And I told him so.

But old Dr. Hertz got out his long bamboo rod and tried tiny feathered flies that floated and tiny flies that sank in the deep pools where the creek gathered before rushing over the falls and down into the cleft.

Naturally, he caught nothing.

He never even got a nibble–or a look, or a flash. I was not surprised. If there were trout in the creek, or anywhere for that matter, worms were the only logical bait. And I told him so. Worms and shiners were the only baits that would take any fish, I firmly announced, and shiners had their limitations.

But I enjoyed going with him, standing by his left side as he cast his long yellow line gracefully back and forth until he dropped a fly noiselessly upon the deep clear pools and then twitched it back and forth or let it rest motionless, perched high and proud. If you could actually catch fish, any fish, this way, I could see its advantages. And the man unquestionably had his skill–though I had not seen him catch a fish, even a sunny, in more than week.

And that mattered.

As for me, I regularly rose a good deal earlier than even the cooks and slipped down to the lake for a little fishing by the shore. I had never been able to persuade the boat-boy, who did not fish, to leave a boat unchained for me; unquestionably, though he was only fourteen, he had already capitulated to the adults and their narrow, unimaginative morality. One morning in the middle of Dr. Hertz’s second, and last, week, I grew bored with the few sunfish and shiners and midget perch available from the dock and followed the creek down through the woods until I came to the little wooden bridge.

I lay on it, stretching myself out full length, feeling the rough weathered boards scrape against my belly and thighs, and peered down into the clear water.

A few tiny dace flittered here and there. I spied a small bullfrog squatting in the mud and rushes on the far left bank–and decided it was not worth my time to take him. Several pebbles slipped through the boards and plunked loudly into the pool. A kingfisher twitted in some nearby oak branches, and another swept low along the stream’s alley and seemed to catch some unseen insect in flight. A small punkinseed zigzagged across my sight. Several tiny whirling bugs spun and danced around the surface of the water. The shadows wavered, auburn and dark, along the sandy bottom of the creek; I watched my own shimmering shadow among them.

And then I saw him.

Or rather, saw just his nose. For the fish was resting, absolutely still, beneath the log-bottom brace of the bridge, with only a trifle more than his rounded snout showing. It was not a punkinseed or a pickerel; shiners would not remain so quiet; it was scarcely a large perch.

And then I saw all of him, for he emerged all at once from beneath the log, moved with long swift gestures–not the streak of the pickerel or the zigzag of the sunfish–and rose to the surface right below my head, no more than two feet below me, breaking the water in a neat little dimple, turning so I could see him, massy, brilliantly colored, sleek and long. And then he returned to beneath the log.

It all happened in a moment: but I knew.

Something dramatic, miraculous, had occurred, and I still feel a quickening of my heart when I conjure up the scene. There was nobility in his movements, a swift surety, a sense of purpose–even of intelligence. Here was a quarry worthy of all a young boy’s skill and ingenuity. Here, clearly, was the fish Dr. Hertz pursued with all his elaborate equipment. And I knew that, no matter what, I had to take that trout.

I debated for several hours whether to tell Dr. Hertz about the fish and finally decided that, since I had discovered him, he should be mine. All that day he lay beneath a log in my mind, while I tried to find some way out of certain unpleasant chores, certain social obligations like entertaining a visiting nephew my age–who simply hated the water. In desperation, I took him to my huge compost pile under the back porch and frightened the living devil out of him with some huge night crawlers–for which I was sent to my room. At dinner I learned that Dr. Hertz had gone off shopping and then to a movie with his wife; good thing, I suppose, for I would surely have spilled it all that evening.

That night I prepared my simple equipment, chose a dozen of my best worms from the compost pile, and tried to sleep.

I could not.

Over and over the massive trout rose in my mind, turned, and returned to beneath the log. I must have stayed awake so long that, out of tiredness, I got up late the next morning–about six.

I slipped quickly out of the deathly still hotel, too preoccupied to nod even to my friend the night clerk, and half ran through the woods to the old wooden bridge.

He was still there! He was still in the same spot beneath the log!

First I went directly upstream of the bridge and floated a worm down to him six or seven times.

Not a budge. Not a look. Was it possible?

I had expected to take him, without fail, on the first drift–which would have been the case were he a perch or huge punkinseed–and then march proudly back to the Laurel House in time to display my prize to Dr. Hertz at breakfast.

I paused and surveyed the situation. Surely trout must eat worms, I speculated. And the morning is always the best time to fish. Something must be wrong with the way the bait is coming to him. That was it.

I drifted the worm down again and noted with satisfaction that it dangled a full four or five inches above his head. Not daring to get closer, I tried casting across stream and allowing the worm to swing around in front of him; but this still did not drop the bait sufficiently. Then I tried letting it drift past him, so that I could suddenly lower the bamboo pole and provide slack line and thus force the worm to drop near him. This almost worked, but, standing on my tiptoes, I could see that it was still too high.

Sinkers? Perhaps that was the answer.

I rummaged around in my pockets, and then turned them out onto a flat rock: penknife, dirty handkerchief, two dried worms, extra snelled hooks wrapped in cellophane, two wine-bottle corks, eleven cents, a couple of keys, two rubber bands, dirt, a crayfish’s paw–but no sinkers, not even a washer or a nut or a screw. I hadn’t used split shot in a full month, not since I had discovered that a freely drifting worm would do much better in the lake and would get quite deep enough in its own sweet time if you had patience.

Which I was long on.

I scoured the shore for a tiny pebble or flat rock and came up with several promising bits of slate; but I could not, with my trembling fingers, adequately fashion them to stay tied to the line. And by now I was sorely hungry, so I decided to get some split shot in town and come back later. That old trout would still be there. He had not budged in all the time I’d fished over him.

I tried for that trout each of the remaining days that week. I fished for him early in the morning and during the afternoon and immediately after supper. I fished for him right up until dark, and twice frightened my mother by returning to the hotel about nine-thirty. I did not tell her about the trout, either.

Would they understand?

And the old monster? He was always there, always beneath the log except for one or two of those sure yet leisurely sweeps to the surface of the crystal stream, haunting, tantalizing.

I brooded about whether to tell Dr. Hertz after all and let him have a go at my trout with his fancy paraphernalia. But it had become a private challenge of wits between that trout and me. He was not like the huge pickerel that haunted the channels between the pads in the lake. Those I would have been glad to share. This was my fish: he was not in the public domain. And anyway, I reasoned, old Dr. Hertz could not possibly walk through the tangled, pathless woods with his bum leg.

On Sunday, the day Dr. Hertz was to leave, I rose especially early–before light had broken–packed every last bit of equipment I owned into a canvas bag, and trekked quickly through the wet woods to the familiar wooden bridge. As I had done each morning that week, I first crept out along the bridge, hearing only the sprinkling of several pebbles that fell between the boards down into the creek, and the twitting of the stream birds, and the bass horn of the bullfrog. Water had stopped coming over the dam at the lake the day before, and I noticed that the stream level had dropped a full six inches. A few dace dimpled the surface, and a few small sunfish meandered here and there.

The trout was still beneath the log.

I tried for him in all the usual ways–upstream, downstream, and from high above him on the bridge. I had by now, with the help of the split shot, managed to get my worm within a millimeter of his nose, regularly; in fact, I several times that morning actually bumped his rounded snout with my worm. The old trout did not seem to mind. He would sort of nudge it away, or ignore it, or shift his position deftly. Clearly he considered me no threat. It was humbling, humiliating.

I worked exceptionally hard for about three hours, missed breakfast, and kept fishing on into late morning on a growling stomach. I even tried floating grasshoppers down to the fish, and then a newt, even a little sunfish I caught upstream, several dace I trapped, and finally a crayfish.

Nothing would budge the monster.

At last I went back to my little canvas pack and began to gather my scattered equipment. I was beaten. And I was starved. I’d tell Dr. Hertz about the fish and if he felt up to it he could try for him.

Despondently, I shoved my gear back into the pack.

And then it happened!

I pricked my finger sorely with a huge Carlisle hook, snelled, which I used for the largest pickerel. I sat down on a rock and looked at it for a moment, pressing the blood out to avoid infection, washing my finger in the spring-cold stream, and then wrapping it with a bit of shirt I tore off–which I’d get hell for. But who cared.

The Carlisle hook! Perhaps, I thought. Perhaps.

I had more than once thought of snaring that trout with piano wire lowered from the bridge, but too little of his nose was exposed. It simply would not have worked.

But the Carlisle hook.

Carefully I tied the snelled hook directly onto the end of my ten-foot bamboo pole, leaving about two inches of firm gut trailing from the end. I pulled it to make sure it was firmly attached, found that it wasn’t, and wrapped a few more feet of gut around the end of the pole to secure it.

Then, taking the pole in my right hand, I lay on my belly and began to crawl with painful slowness along the bottom logs of the bridge so that I would eventually pass directly above the trout. It took a full ten minutes. Finally, I was there, no more than a foot from the nose of my quarry, directly over him.

I scrutinized him closely for a long moment, lowering my head until my nose twitched the surface of the low water but a few inches from his nose.

He did not move.

I did not move.

I watched the gills dilate slowly; I followed the length of him as far back beneath the log as I could; I could have counted his speckles. And I trembled.

Then I began to lower the end of the rod slowly, slowly into the water, slightly upstream, moving the long bare Carlisle hook closer and closer to his nose.

The trout opened and closed its mouth just a trifle every few seconds.

Now the hook was fractions of an inch from its mouth. Should I jerk hard? Try for the under lip? No, it might slip away–and there would be only one chance. Instead, I meticulously slipped the bare hook directly toward the slight slit that was his mouth, guiding it down, into, and behind the curve of his lip.

He did not budge. I did not breathe.

And then I jerked up!

The fish lurched. I yanked. The bamboo rod splintered but held. The trout flipped up out of his element and into mine and flopped against the buttresses of the bridge. I pounced on him with both hands, and it was all over. It had taken no more than a few seconds.

Back at the hotel I headed immediately for Dr. Hertz’s room, the seventeen-inch trout casually hanging from a forked stick in my right hand. To my immense disappointment, he had gone.

I wrote to him that very afternoon, lying in my teeth.

Dear Doctor Hertz:

I caught a great big trout on a worm this morning and brought it to your room but you had gone home already. I have put into this letter a diagram of the fish that I drew. I caught him on a worm.

I could have caught him on a worm, eventually, and anyway I wanted to rub it in that he’d nearly wasted two weeks of my time and would never catch anything on those feathers. It would be a valuable lesson for him.

Several days later I received the letter below, which I found some months ago in one of my three closets crammed with fly boxes, waders, fly-tying tools and materials, delicate fly rods, and the rest of that equipment needed for an art no less exhaustible than the “Mathematics.”

Dear Nicky:

I am glad you caught a big trout. But after fishing that creek hard I am convinced that there just weren’t any trout in it. Are you sure it wasn’t a perch? Your amusing picture looked like it. I wish you’d sent me a photograph instead, so I could be sure. Perhaps next year we can fish a

real trout stream together.

Your friend, Thos. Hertz, M.D.

Real? Was that unnamed creek not the realest I have ever fished? And “your friend.” How could he say that?

But let him doubt: I had, by hook and by crook, caught my first trout.

And when I have dreamed that first trout a thousand times, it is time to think of the present. For the new year has turned.

Then, inside me, the spring trout begin to stir: I feel them deep in their thawing streams–lethargic, slow. I begin to feel the coverts gouged out of the stream floors, the tangled roots and waterlogged branches, the whitened riffles and soft sod banks. Yes, the year has turned. And has not Frank written me: “There are forty-three days left until the season opens, Nick–and you had better give some serious thought to your tying.” And he encloses a spritely barred rock neck and, on the spot, I tie up three Spent-wing Adamses.

And then it is time to lay down Schwiebert and Jennings, to set aside Halford and Marinaro, to put up my Walton with those well-underlined passages. I begin to frequent the tackle stores during lunch hour; I stop off at Abercrombie’s on my way to work to flex a Payne rod (for what day is not blessed by having first flexed a Payne); I write out an elaborate order to Orvis–but realize it is far beyond my means and whittle it down; a bit of wood duck, an impala tail, floss, assorted necks, two spools of fine silk threat arrive from the economical Herter’s. And then, in the evenings–all the tugs and tightenings of the day dissolved–I sit down at my vise and begin to tie.

In my salad days, February and March were filled with action. To wet an early line, I would travel to Steeplechase pier at Coney Island and stand, near-frozen, with other hardy souls on a windy day casting lead and spearing down for ugly hackleheads, skates, and miniature porgies. Later I would practice fly-casting on the snow–or in gymnasiums. And as March grew I would wade the tidal flats for winter flounder and that strange grab bag of the seas found at the Long Island shore.

But now I am older and can wait less anxiously. Sometimes. I try to remember that the season will come in its own good time. It cannot be rushed.

My hands are busy at the vise; I use the back of a match to seal and varnish a last guide or two; I send for travel folders I cannot afford to use; I remember a huge trout rising in a small unnamed creek, a little boy slipping a bare Carlisle hook up into its mouth–and then, with a momentous yank, the new season has begun.

Chapter Three

THE LURE OF OPENING DAY

Who so that first to mille comth, first grynt. –Geoffrey Chaucer, Prologue to “The Wife of Bath’s Tale”

The whole madness of Opening Day fever is quite beyond me: it deserves the complexities of a Jung or a Kafka, for it is archetypal and rampant with ambiguity. And still you would not have it.

Is it simply the beginning of a new season, after months of winter dreams?

That it is one day–like a special parade, with clowns and trumpets–that is bound by short time, unpredictable weather, habit, ritual?

That it is some massive endurance test?

Or the fact that the usually overfished streams are as virgin as they’ll ever be?

That there are big fish astream–for you have caught your largest on this day?

Masochism–pure and simple?

A submergence syndrome?

That you are the first of the year–or hope to be? And will “first grynt”?

I don’t know. I simply cannot explain it. When I am wise and strong enough (or bludgeoned enough), I know I shall resist even thinking of it. I know for sure only that March is the cruelest month–for trout fishermen. And that the weakest succumb, while even the strongest must consciously avoid the pernicious lure of Opening Day.

On approximately March fourth, give or take a day–I get up from my desk year after year and industriously slip into the reference room, where I spend hours busily studying the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Volume I, under “Angling”: looking at pictures of fat brook trout being taken from the Nipigon River, impossible Atlantic salmon bent heavy in a ghillie’s net, reading about Halford and Skues and the immaculate Gordon and some fool in Macedonia who perhaps started it all.

Then on lunch hours I’ll head like a rainbow trout, upstream, to the Angler’s Cove or the Roost or the ninth floor at Abercrombie’s–sidle up to groups rehashing trips to the Miramichi, the Dennys, the Madison, the Au Sable, the Beaverkill, and “this lovely little river filled with nothing smaller than two-pounders, and every one of ’em dupes for a number twenty-six Rube Winger.”

It is hell.

I listen intently, unobtrusively, as each trout is caught, make allowances for the inescapable fancy, and then spend the rest of the day at my desk scheming for this year’s trips and doodling new fly patterns on manuscripts I am supposed to be editing. Or some days I’ll head downstream, and study the long counter of luscious flies under glass at the elegant William Mills’, hunting for new patterns to tie during the last March flurry of vise activity.

It is a vice–all of it: the dreaming, the reading, the talking, the scant hours (in proportion to all else) of fishing itself. How many days in March I try to get a decent afternoon’s work done, only to be plagued, bruited and beaten, by images of browns rising steadily to Light Cahills on the Amawalk, manic Green Drake hatches on the big Beaverkill, with dozens of fat fish sharking down the ample duns in slow water. I fish a dozen remembered streams, two dozen from my reading, a dozen times each, every riffle and eddy and run and rip and pool of them, every March in my mind. I become quite convinced that I am going mad. Downright berserk. Fantasy becomes reality. I will be reading at my desk and my body will suddenly stiffen, lurch back from the strike; I will see, actually see, four, five, six trout rolling and flouncing under the alder branch near my dictionary, glutting on leaf rollers–or a long dark shadow under a far ledge of books, emerging, dimpling the surface, returning to its feeding post.

My desk does not help. I have it filled with every conceivable aid to such fantasies. Matching the Hatch, Art Flick’s Streamside Guide, The Dry Fly and Fast Water reside safely behind brown paper covers–always available. There are six or seven catalogs of flyfishing equipment–from Orvis and Norm Thompson and Dan Bailey and Herter’s and Mills’; travel folders from Maine, Idaho, Quebec, Colorado–all with unmentionable photos of gigantic trout and salmon on them; I have four Sulfur Duns that Jim Mulligan dropped off on a visit–that I could bring home; and there is even a small box of No. 16 Mustad dry-fly hooks and some yellow-green wool, from which I can tie up a few heretical leafrollers periodically, hooking the barb into a soft part of the end of the desk, and working furtively, so no one will catch me and think me quite so troutsick mad as I am.

But no. It is no good. I will not make it this year. I cannot wait until mid-May. Even then there will be difficulty abandoning Mari and my children (still under trouting size) for merely a day’s outing.

And yet for many years there was this dilemma: after years of deadly worming and spinning, I became for a time a rabid purist, shunning even streamers and wet flies. How could I fish Opening Day with dries? It was ludicrous. It was nearly fatal.

But it was not always so.

I can remember vividly my first Opening Day, and I can remember, individually, each of the ten that succeeded it, once at the expense of the college-entrance examinations, once when I went AWOL from Fort Dix, and once … well … when I was in love.

A worm dangled from a nine-foot steel telescopic rod took my second trout. He was only a stocked brown of about nine inches, and I took him after three hours of fishing below the Brewster bridge of the East Branch of the Croton; I was just thirteen and it was the height of the summer.

On Opening Days you can always see pictures of the spot in the New York papers. Draped men, like manikins, pose near the falls upstream; and Joe X of 54-32 Seventy-third Avenue is standing proudly with his four mummy buddies, displaying his fat sixteen-inch holdover brown, the prize of the day; a buddy has ten–are they smelt? You do not die of loneliness on the East Branch of the Croton these days.

Probably it was always like that. But memory is maverick: the crowds are not what I remember about the East Branch–not, certainly, what I remember about my first day.

In the five years since I had caught my first trout, I had fished often for largemouth bass, pickerel, perch, sunfish, catfish, crappies, and even shiners–always with live bait, usually with worms, always in lakes or ponds. Once, when my mother tried to interest me in horseback riding, I paused at a creek along the trail, dismounted, and spent an hour fishing with a pocket rig I always carried.

It could not have been the nine-inch hollow- and gray-bellied brown that intrigued me all that winter. Perhaps it was the moving water of the stream, the heightened complexity of this kind of fishing. Perhaps it was the great mystery of moving water. What does Hesse’s Siddhartha see in the river? “He saw that the water continually flowed and flowed and yet it was always there; it was always the same and yet every moment it was new.” He saw, I suppose, men, and ages, and civilizations, and the natural processes.

Whatever the cause, the stream hooked me, too. All that winter I planned for my first Opening Day. There were periodic trips to the tackle stores on Nassau Street, near my stepfather’s office; interminable lists of necessary equipment; constant and thorough study of all the outdoor magazines, which I would pounce on the day they reached the stands.

My parents were out of town the weekend the season was too pen, and my old grandmother was staying with me. My plan was to make the five forty-five milk train out of Grand Central and arrive in Brewster, alone, about eight. My trip had been approved.

I arose, scarcely having slept, at two-thirty by the alarm and went directly to the cellar, where all my gear had been carefully laid out. For a full ten days.

I had my steel fly rod neatly tied in its canvas case, a hundred and fifty worms (so that I would not be caught short), seventy-five No. 10 Eagle Claw hooks (for the same reason), two jackknives (in case I lost one), an extra spool of level fly line, two sweaters (to go with the sweatshirt, sweater, and woolen shirt I already wore under my mackinaw), a rain cape, four cans of Heinz pork and beans, a whole box of kitchen matches in a rubber bag (one of the sporting magazines had recommended this), a small frying pan, a large frying pan, a spoon, three forks, three extra pairs of woolen socks, two pairs of underwear, three extra T-shirts, an article from one of the magazines on “Early Season Angling” (which I had plucked from my burgeoning files), two tin cups, a bottle of Coca-Cola, a pair of corduroy trousers, a stringer, about a pound a half of split shot, seven hand-tied leaders, my bait-casting reel, my fly reel, and nine slices of rye bread. Since I had brought it down to the cellar several days earlier, the rye bread was stale.

All of this went (as I knew it would, since I had packed four times, for practice) into my upper pack. To it I attached a slightly smaller, lower pack, into which I had already put my hip boots, two cans of Sterno, two pairs of shoes, and a gigantic thermos of hot chocolate (by then cold).

Once the two packs were fastened tightly, I tied my rod across the top (so that my hands would be free), flopped my felt hat down hard on my head, and began to mount my cross.

Unfortunately, my arms would not bend sufficiently beneath the mackinaw, the sweater, the woolen shirt, and the sweatshirt–I had not planned on this–and I could not get my left arm through the arm-strap.

My old grandmother had risen to see me off with a good hot breakfast, and hearing me moan and struggle, came down to be of help.

She was of enormous help.

She got behind me, right down on the floor, on my instructions, in the dimly lit basement at three in the morning, and pushed up. I pushed down.

After a few moments I could feel the canvas strap.

“Just a little further, Grandma,” I said. “Uhhh. A … litt … ul … more.”

She pushed and pushed, groaning now nearly as loudly as I was, and then I said, “NOW!” quite loudly and the good old lady leaped and pushed up with all her might and I pushed down and my fingers were inside the strap and in another moment the momentous double pack was on my back.

I looked thankfully at my grandmother standing (with her huge breasts half out of her nightgown) beneath the hanging light bulb. She looked bushed. After a short round of congratulations, I told her to go up the narrow stairs first. Wisely she advised otherwise, and I began the ascent. But after two steps I remembered that I hadn’t taken my creel, which happened to contain three apples, two bananas, my toothbrush, a haft pound of raisins, and two newly made salami sandwiches.

Since it would be a trifle difficult to turn around, and I was too much out of breath to talk, I simply motioned to her to hand me the creel from the table. She did so, and I laboriously strapped it around my body, running the straps, with Grandma’s help, under the pack.

Then I took a step. And then another. I could not take the third. My steel fly rod, flanged out at the sides, had gotten wedged into the narrow stairwell. In fact, since I had moved upstairs with some determination, it was jammed tightly between the two-by-four banister and the bottom of the ceiling.

It was a terrifying moment. I could be there all day. For weeks.

And then I’d miss Opening Day.

Which I’d planned all that winter.

I pulled. Grandma pushed. We got nowhere. But then, in her wisdom, she found the solution: remove the rod. She soon did so, and I sailed up the stairs at one a minute.

A few moment later I was at the door. “I’ll … have … to hurry,” I panted. It’s three thirty-five … already.”

She nodded and patted me on the hump. As I trudged out into the icy night. I heard her say, “Such a pack! Such a little man!”

The walk to the subway was only seventeen blocks, and I made it despite the lower pack smacking painfully at each step against my rump. I dared not get out of my packs in the subway, so I stood all the way to Grand Central, in near-empty cars, glared at by two bums, one high-school couple returning from a dress dance, and several early workers who appeared to have seen worse.

The five forty-five milk train left on time, and I was on it. I unhitched my packs (which I did not–could not–replace all that long day, and thus carried by hand), and tried to sleep. But I could not: I never sleep before I fish.

The train arrived at eight, and I went directly to the flooding East Branch and rigged up. It was cold as a witch’s nose, and the line kept freezing at the guides. I’d suck out the ice, cast twice, and find ice caked at the guides again. After a few moments at a pool, I’d pick up all my gear, cradling it in my arms, and push on for another likely spot. Four hours later I had still not gotten my first nibble.

Then a sleety sort of rain began, which slowly penetrated through all my many layers of clothing right to the marrowbone. But by four o’clock my luck had begun to change. For one good thing, I had managed to lose my lower pack and thus, after a few frantic moments of searching, realized that I was much less weighted down. For another, it had stopped raining and the temperature had risen to slightly above freezing. And finally, I had reached a little feeder creek and had begun to catch fish steadily. One, then another, and then two more in quick succession.

They weren’t trout, but a plump greenish fish that I could not identify. They certainly weren’t yellow perch or the grayish largemouth bass I had caught. But they were about twelve to fourteen inches long and gave quite an account of themselves after they took my night crawler and the red-and-white bobber bounced underwater.

They stripped line from my fly reel, jumped two or three times, and would not be brought to net without an impressive struggle.

Could they be green perch? Whatever they were, I was pleased with myself and had strung four of them onto my stringer and just lofted out another night crawler when a genial man with green trousers and a short green jacket approached.

“How’re you doin’, son?” he asked.

“Very well,” I said, without turning around. I didn’t want to miss that bobber going under.

“Trout?”

“Nope. Not sure what they are. Are there green perch in this stream?”

“Green perch?”

Just then the bobber went under abruptly and I struck back and was into another fine fish. I played him with particular care for my audience and in a few moments brought him, belly up, to the net.

The gentleman in back of me had stepped close. “Better release him right in the water, son; won’t hurt him that way.”

“I guess I’ll keep this one, too,” I said, raising the fish high in the net. It was a beautiful fish–all shining green and fat and still flopping in the black meshes of the net. I was thrilled. Especially since I’d had an audience.

“Better return him now,” the man said, a bit more firmly. “Bass season doesn’t start until July first.”

“Bass?”

“You’ve got a nice smallmouth there. They come up this creek every spring to spawn. Did’ya say you’d caught some more?”

I knew the bass season didn’t start until July. Anybody with half a brain knew that. So when the man in green said it was a bass I disengaged the hook quickly and slipped the fish carefully back into the water.

“I’m a warden, son,” the man said. “Did you say you’d caught s’more of these bass?”

“Yes,” I said, beginning to shake. It was still very cold and the sun had begun to drop. “Four.”

“Kill them?” he asked sternly.

“They’re on my stringer,” I said, and proceeded to walk the few yards upstream to where the four fish, threaded through the gills, were fanning the cold water slowly.

“Certainly hope those fish aren’t dead,” said the warden.

I did not take the stringer out of the icy water but, with all the grace and sensitivity I could possibly muster, and with shaking hands, began to slip the fish off and into the current. The first floated out and immediately began to swim off slowly; so did the other two–each a bit more slowly. The fourth had been on the stringer for about fifteen minutes. I had my doubts. Carefully I slipped the cord through his gills and pushed him out, too.

He floated downstream, belly up, for a few moments.

“Hmmm,” murmured the warden.

“His tail moved; I’m sure it did,” I said.

“Don’t think this one will make it.”

Together we walked downstream, following the fish intently. Every now and then it would turn ever so slowly, fan its tail, and flop back belly up again. There was no hope. Down the current it floated, feeble, mangled by an outright poacher, a near goner. When it reached the end of the feeder creek and was about to enter the main water, it swirled listlessly in a small eddy, tangled in the reeds, and was dead still for a long moment.

But then it made a momentous effort, taking its will from my will perhaps, and its green back was up and it was wriggling and its green back stayed up and I nearly jumped ten feet with joy.

“Guess he’ll make it,” said the warden.

“Guess so,” I said, matter-of-factly.

“Don’t take any more of those green perch now, will you?” he said, poker-faced, as he turned and walked back up the hill. “And get a good identification book!”

I breathed heavily, smiled, and realized that my feet were almost frozen solid. So I began to fold in my rod, gather together my various remaining goods–almost all unused–and prepare to leave. I cradled my pack in my arms and trudged up the hill to the railway station, glad I’d taken some fish, glad the fish had lived.

It was ten o’clock that night when I returned. Somehow I stumbled up the stairs and, with a brave whistle, kissed my grandmother on the cheek. She did not look like she would survive the shock of me. Then, without a word, I collapsed.

©2000 by Nick Lyons. Reprinted with permission from Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.