With the electric light as a sorcerer’s apprentice, Coney Island’s three great amusement parks–Steeplechase, Luna Park, and Dreamland–conjured up a “city of fire,” its eerie aurora visible 30 miles out to sea. It dazzled all who saw it at the turn of the century. One writer described Luna as a “cemetery of fire” whose “tombs and turrets and towers [were] illuminated in mortuary shafts of flame.” Even the saturnine Maxim Gorky was swept up in a transport of rapture at the sight of Luna at night, its spires, domes, and minarets ablaze with a quarter of a million lights. “Golden gossamer threads tremble in the air,” he wrote. “They intertwine in transparent, flaming patterns, which flutter and melt away, in love with their own beauty mirrored in the waters. Fabulous beyond conceiving, ineffably beautiful, is this fiery scintillation.

” Another writer called Coney a “pyrotechnic insanitarium,” a phrase straight out of a carny barker’s pitch that perfectly captures the island’s signature blend of infernal fun and mass madness, technology and pathology.

On the day that Dreamland burned, the island became a pyrotechnic insanitarium in ghastly fact. In the small hours of the morning on May 27, 1911, a fire broke out in Hell Gate, a boat ride into the bottomless pit. The inferno tore through Dreamland’s lathe-and-plaster buildings, the “uncontrolled flames leaping higher than any of Coney’s towers, animals screaming from within cages where they were trapped to burn to death, and crazed lions … running with burning manes through the streets”–a scene worthy of Salvador Dali at his most delirious. In three hours, the wedding-cake fantasia of virgin-white palaces, columns, and statuary was reduced to acres of smoldering ruins, never to be rebuilt.

Now, as we stand at the fin-de-millennium, Dreamland is burning again.

It’s a commonplace that something is “out of kilter” in America, as Senator John Kerry put it in the aftermath of the Oklahoma bombing; that “everything that’s tied down is coming loose,” as Bill Moyers has observed; that “the world has gone crazy,” as the Unabomber declared, in his official capacity as Op-Ed essayist and mad bomber.

The Unabomber is a man with his finger on the nation’s pulse–or is it a detonator? These are the days of “burn-and-blow,” in bomb-squad lingo, from the mass destruction in Oklahoma City and the World Trade Center to the explosion at the Atlanta Olympic Park. The live grenade found in a newspaper-vending box in Albuquerque is just one more statistic in the growing number of bombings, up to 1,880 in 1993 from 442 a decade earlier.

There’s a growing belief that mere anarchy is loosed upon the world, as Yeats foretold; that the best lack all conviction, while the worst–terrorists like the Unabomber and Timothy McVeigh, cult leaders like David Koresh of the Branch Davidians and Marshall Applewhite of Heaven’s Gate fame–are full of passionate intensity. The cultural critic James Gardner believes that we live in “an age of extremism,” a time of “infinite fracturing and polarizing,” when extremism “has become the first rather than the last resort.”

In Don DeLillo’s Underworld, a character laments the end of the Cold War: “Many things that were anchored to the balance of power and the balance of terror seem to be undone, unstuck. Things have no limits, now…. Violence is easier now, it’s uprooted, out of control, it has no measure anymore, it has no level of values.” A headline in The New York Times says it all: A WHOLE NEW WORLD OF ARMS RACES TO CONTAIN. The Bomb, which used to be the measure of a superpower’s John Wayne manhood, seems a little less impressive in a world where technology and the post-Cold War arms market have outfitted many Third World countries with nukes of their own, ballistic missiles armed with poison gas, or deadly germs. And for truly cash-strapped nations, there’s always the devastatingly effective car bomb–”the poor man’s substitute for an air force,” in the words of one counterinsurgency expert.

Worse yet, we live at a moment when a lone wacko, like the mad scientist in Richard Preston’s 1997 novel The Cobra Event, could tinker together the biological equivalent of a suitcase nuke. President Clinton, whom aides have described as “fixated” on the threat of germ warfare, was so unnerved by Preston’s tale of a sociopath who terrorizes New York City with a genetically engineered “brainpox” that he ordered intelligence experts to evaluate its credibility. The book apparently played a catalytic role in Clinton’s decision to initiate a hastily conceived multi-million-dollar project to stockpile vaccines at strategic points around the country.

Even nature seems to be committing random acts of senseless violence, from airborne plagues like the Ebola virus to the chaos wrought by El Nino. Sometimes, of course, nature has a little help from our highly industrialized society, which has introduced us to the delights of food-related illnesses like mad-cow disease and postmodern maladies like multiple chemical sensitivity, poetically known as “twentieth-century disease.”

Between 1980 and 1990, the number of fungal infections in hospitals doubled, many of them attributable to virulent new supergerms that eat antibiotics for breakfast. Sales of antibacterial soaps, a voodoo charm against the unseen menaces of staph and strep and worse, are up. So, too, is the consumption of bottled water–a “purified” alternative to the supposed toxic soup of lead, chlorine, E. coli, and cryptosporidium that slithers out of our taps. The Brita filter is our fallout shelter, the existential personal flotation device of the nervous nineties.

But, all this gloom and doom notwithstanding, there’s a darkly farcical, Coneyesque quality to the nineties, a decade captivated by celebrity nonentities like Joey Buttafuoco and Tonya Harding and Lorena Bobbitt and Heidi Fleiss and, as this is written, the cast of “zippergate,” starring Monica Lewinsky. The increasingly black comedy of American society is writ small in the information flotsam that drifts with the media current–back-page stories like the one about the Long Island men accused of conspiring to kill local politicians, whom they believed were concealing evidence of a flying saucer crash, by lacing the officials’ toothpaste with radioactive metal.

The postmodern theorist Arthur Kroker believes that millennial culture is manic-depressive, mood-swinging between “ecstasy and fear, between delirium and anxiety.” For Kroker, the “postmodern scene” is a panic, in the sense of the “panic terror” that some historians believe swept through Europe at the turn of the last millennium, when omens of apocalypse supposedly inspired public flagellation and private suicides. But, he implies, it’s also a panic in the somewhat dated sense of something that’s hysterically funny (with the emphasis on hysterical). Fin-de-millennium America is an infernal carnival–a pyrotechnic insanitarium, like Coney Island at the fin-de-siecle.

The Electric Id: Coney Island’s Infernal Carnival

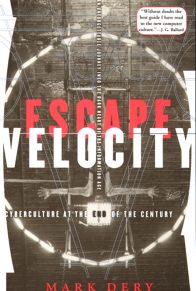

Our historical moment parallels Coney’s in its heyday: In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, America was poised between the Victorian era and the Machine Age; similarly, we’re in transition from industrial modernity to the Digital Age. Like Americans at the last fin-de-siecle, we have a weakness for those paeans to the machine that Leo Marx called “the rhetoric of the technological sublime.” Nicholas Negroponte, the director of MIT’s Media Lab and the author of the gadget-happy technology tract, Being Digital, believes that digital technologies are a “force of nature, decentralizing, globalizing, harmonizing, and empowering.” Fellow traveler John Perry Barlow, a breathless cyberbooster, proclaims a millennial gospel that borrows equally from the Jesuit philosopher Teilhard de Chardin, Marshall McLuhan, and Deadhead flashbacks to the sixties notion that we’re all connected by a cosmic web of psychic Oobleck. In the media and on the lecture circuit, Barlow heralds the imminent “physical wiring of collective human consciousness” into a “collective organism of mind,” perhaps even divine mind.

In the middle of the last century, writers similarly intoxicated by the invention of wireless telegraphy had equally giddy visions. “It is impossible that old prejudices and hostilities should longer exist, while such an instrument has been created for an exchange of thought between all the nations of the earth,” Charles Briggs and Augustus Maverick wrote of the telegram in 1858. In 1899, a pop science magazine informed its readers that “the nerves of the whole world” were “being bound together” by Marconi’s marvel; world peace and the Brotherhood of Man were at hand.

Our dizzy technophilia would have been right at home in Coney, where revelers thrilled to Luna’s Trip to the Moon, Dreamland’s Leap-Frog Railway (which enabled one train to glide safely over another on the same track), and the world’s greatest displays of that still-novel technology, the electric light. Dreamland’s powerhouse was a temple of electricity with a facade designed to look like a dynamo; inside, a white-gloved engineer ministered to the machines and lectured awed visitors on the wonders of electrical power.

But the what-me-worry futurism of cyberprophets like Barlow shares cultural airspace, as did Coney’s visions of technological promise in their day, with the pervasive feeling that American society is out of control. Politicians and pundits bemoan the death of community and the dearth of civility, the social pathologies caused by the withering of economic opportunity for blue-collar workers or the breakdown of the family or the decline of public education or the acid rain of media violence or all of the above.

Coney’s Jules Verne daydreams of high-tech tomorrows took place against a backdrop of profound social change and moral disequilibrium. Turn-of-the-century America was accelerating away from the starched manners and corseted mores of the Victorian age, toward a popular culture shaped by mass production, mass media, and the emerging ethos of conspicuous consumption. Coney’s parks were agents of social transformation, briefly repealing the hidebound proprieties of the Victorian world and helping to weave heterogeneous social, ethnic, and economic groups into a mass consumer society.

America was moving from what the economist and social theorist Simon Patten, writing at the peak of Coney’s popularity, called a “pain economy” of scarcity and subsistence to a “pleasure economy” that held out at least the promise of abundance. Steeplechase’s trademark”–funny face”–a leering clown with an ear-to-ear, sharklike grin–personified the infantile psychology of the new consumer culture, with its emphasis on immediate gratification and sensual indulgence. Coney was a social safety valve for an ever more industrialized, urbanized America, appropriating the machines of industry in the service of the unconscious. (Fittingly, Sigmund Freud had just opened a Dreamland of his own in The Interpretation of Dreams, a book published in 1899 but shrewdly imprinted with the momentous date of 1900 by Freud’s savvy publisher).

At once a parody of industrial modernity and an initiation into it, Coney was a carnival of chaos, a madcap celebration of emotional abandon and exposed flesh, speed and sensory overload, natural disasters and machines gone haywire. Rides like Steeplechase’s Barrel of Love and Human Roulette Wheel hurtled young men and women into deliciously indecent proximity, and hidden blow holes whipped skirts skyward, exposing the scandalous sight of bare legs. (This at a time when, according to the historian John F. Kasson, “the middle-class ideal as described in etiquette books of the period placed severe restraints on the circumstances under which a man might presume even to tip his hat to a woman in public.”)

The Russian critic and literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin coined the term “carnivalesque” to describe the high-spirited subversion, in medieval carnivals, of social codes and cultural hierarchies. Similarly, Steeplechase, Luna, and Dreamland turned the Victorian world upside down in an eruption of what might be called the “electric carnivalesque.” According to Kasson, Coney “declared a moral holiday for all who entered its gates. Against the values of thrift, sobriety, industry, and ambition, it encouraged extravagance, gaiety, abandon, revelry. Coney Island signaled the rise of a new mass culture no longer deferential to genteel tastes and values, which demanded a democratic resort of its own. It served as a Feast of Fools for an urban-industrial society.”

But to much of what we would now call the cultural elite, Coney looked less like a Dionysian feast than like the grotesque banquet in Tod Browning’s Freaks. As a “gigantic laboratory of human nature … cut loose from repressions and restrictions,” in the words of the son of Steeplechase’s founder, amusement parks offered a precognitive glimpse of the emerging mass culture of the Machine Age. The cultural critic James Huneker, for one, had seen the future, and was duly appalled. “What a sight the poor make in the moonlight!” he shuddered. Where modernist painters like Joseph Stella delighted in the “carnal frenzy” of Coney’s “surging crowd,” Huneker recoiled in horror from the raucous masses. No fan of Freud’s “return of the repressed,” he pronounced Luna Park a house of bedlam in a frighteningly literal sense. “After the species of straitjacket that we wear everyday is removed at such Saturnalia as Coney Island,” he wrote, “the human animal emerges in a not precisely winning guise…. Once en masse, humanity sheds its civilization and becomes half child, half savage…. It will lynch an innocent man or glorify a scamp politician with equal facility. Hence the monstrous debauch of the fancy at Coney Island, where New York chases its chimera of pleasure.”

Huneker gave voice to middle-class anxieties about the revolt of the masses, their simmering sense of social injustice brought to a boil by urban squalor and industrial exploitation. At the same time, he bore witness to the growing influence of ideas imported from social psychology, such as the notion that surrendering to one’s unconscious impulses could invite actual lunacy, or the theory that the crowd, as a psychological entity, was irrational and immoral–a fertile agar for the culturing of “popular delusions” and mob violence.

Coney materialized the waking nightmares of a middle class haunted by the specters of working-class unrest and the “mongrelization” of Anglo-Saxon America by recent waves of swarthy immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. To Huneker and his constituency, Coney’s “Saturnalia” marked the passing of the Enlightenment vision of the public as an informed, literate body, responsive to reasoned argument and objective fact. In its place, Coney ushered in the crowd psyche of mass consumer culture–low-brow rather than highbrow, reactive rather than reflective, post-literate rather than literate, susceptible to the manipulation of images rather than the articulation of ideas.

The primacy of images in the new mass culture, a sea change that inverted the traditional hegemony of reality over representation, was especially disconcerting. In his hugely influential 1895 book, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind, the French social psychologist Gustave Le Bon argued that the crowd “thinks in images,” confusing “with the real event what the deforming action of its imagination has imposed thereon. A crowd scarcely distinguishes between the subjective and the objective. It accepts as real the images evoked in its mind.” Coney represented the apotheosis of the fake, and critics like Huneker were unsettled by its perverse mockery of palpable fact and visual truth, from its impossibly opulent “marble” facades (a mixture of cement, plaster, and jute fibers) to the larger-than-life spectacles of its staged disasters and simulated adventures. Confronted with the “jumbled nightmares” of Luna’s architecture–a proto-postmodern melange of baroque grotesques and Arabian Nights–Huneker observed, “Unreality is as greedily craved by the mob as alcohol by the dipsomaniac.”

Coney is as good a symbol as any of the historical process William Irwin Thompson calls “the American replacement of nature.” The phenomenon gathered speed in Coney’s heyday with the fateful conjunction of Technologies of reproduction such as chromolithography (1840s) and motion pictures (1895) and the rise of a consumer culture mesmerized by the images of desire made possible by such technologies. The trend had begun in the 1830s with photography, whose ability to skin the visual image inspired Oliver Wendell Holmes to declare that “form is henceforth divorced from matter.” Its runaway acceleration continues in our wired world, where Barlow proposes that the inhabitants of the Internet should secede from reality, since cyberspace isn’t bound by the legal or social codes of the embodied world, which are “based on matter” and “there is no matter here.” In the Luna Park we now inhabit, the permeable membrane between fact and fiction, actual and virtual, is in danger of dissolving altogether.

Dreamland’s fiery demise marked the end of an age. “It took people awhile to realize that they hadn’t just lost a park, that something had changed,” notes American Heritage editor Richard Snow. By the 1920s, Coney was a victim of its own success. It still glowed as brightly as ever, attracting crowds of a million on a good day where once it drew a few hundred thousand, but now it was merely a peeling pasteboard temple of cheap thrills and popular pleasures, not the electric apparition of a coming age. “The authority of the older genteel order that the amusement capital had challenged was now crumbling rapidly, and opportunities for mass entertainment were more abundant than ever,” writes Kasson. “A harbinger of the new mass culture, Coney Island lost its distinctiveness by the very triumph of its values.”

On September 20, 1964, the lights at Coney’s last surviving park, Steeplechase, went out forever, one at a time, as a bell tolled once for each of the 67 years the park had been open and a band played “Auld Lang Syne.” But Coney’s disappearance into history only conceals the fact that all of America has become a pyrotechnic insanitarium.

Trust No One: Conspiracy Theory in the Age of True Lies

Keepers of the Enlightenment flame like Huneker worried about the reign of unreality and unreason at Luna Park, but reassured themselves that the sleep of reason ended at its gates. By contrast, contemporary rationalists see themselves as embattled guardians of the guttering candle of reason in a new dark age.

In The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, Carl Sagan worries that “as the millennium edges nearer, pseudoscience and superstition will seem year by year more tempting, the siren song of unreason more sonorous and attractive.” The Skeptical Inquirer, the house organ of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal, resounds with nervous talk of growing scientific illiteracy and the “rebellion against science at the end of the twentieth century by a populace weary and increasingly wary of the human and environmental costs of military-industrial abuses of science. A recent issue announced “an unprecedented $20 million drive for the future of science and reason,” grimly noting, “Human beings have never understood the material universe as thoroughly as they do today. Yet never has the popular hunger for superstition, pseudoscience, and the paranormal been so acute.”

Ironically, millennial America is also gnawed by that all too rational rage for order known as conspiracy theory–the belief that nothing is meaningless, that all of history’s seemingly loose ends are interwoven in a cosmic cat’s cradle of dark import. The grand design of this tangled worldwide web is known only to the unseen schemers who secretly weave our reality–and to those few of us who TRUST NO ONE, but who know that THE TRUTH IS OUT THERE, as The X-Files has it. Fox “Spooky” Muldur, the X-Files agent obsessed with unraveling the conspiracy’s Gordian knot, is our Everyman, a quintessentially nineties blend of smirking cynic (about official institutions) and true believer (in seemingly everything else, from shape-shifting Indians to telekinetic fire starters to reincarnated serial killers to garden-variety E.T.s).

Conspiracy theory is at once a symptom of millennial angst and a home remedy for it. An ectoplasmic manifestation of our loss of faith in authorities of every sort, it confirms our worst fears that the official reality, from Watergate to Waco, is merely a cover story for moral horrors that would make the portrait of Dorian Gray look like a Norman Rockwell.

But conspiracy beliefs are also a source of cold comfort. At the end of the century that gave us the Theory of Relativity, the Uncertainty Principle, and the Incompleteness Theorem, conspiracy theory returns us to a comfortingly clockwork universe, before the materialist bedrock of our worldview turned to quicksand. Conspiracy theory is a magic spell against the Information Age, an incantation that wards off information madness by organizing every scrap of the free-floating data assaulting us into an impossibly ordered scheme. Unified field theories for a hopelessly complex, chaotic world, conspiracy beliefs are curiously reassuring in their “proof” that someone, somewhere is in charge.

Conspiracy theory is the theology of the paranoid, what Marx might have called the opiate of the fringes if he’d lived to read The New World Order by Pat Robertson. It “replaces religion as a means of mapping the world without disenchanting it, robbing it of its mystery,” writes the literary critic John A. McClure. It “explains the world, as religion does, without elucidating it, by positing the existence of hidden forces which permeate and transcend the realm of ordinary life.”

Like fundamentalist Christianity, conspiracy theory accepts on faith the presumption that social issues can be reduced to a Manichean struggle between good and evil. Like the New Age, it embraces a faith in the interconnectedness of all things, a cosmic holism not unrelated to the “holographic universes,” “morphogenetic fields,” and “nonlocal connectedness” of quantum mysticism. The one-world government of conspiratorial nightmares offers a paranoid analogue to the coming “planetary consciousness” of New Age prophecies.

Conversely, the New Age has its own Smiley-face take on conspiracy theory in Marilyn Ferguson’s Aquarian Conspiracy, in which she holds that undercover agents of cosmic consciousness have infiltrated secular culture like some transcendental fifth column. Then, too, there’s the gaggingly cute New Age concept of “pronoia”–the sneaking suspicion that everyone is conspiring to help you.

Conspiracy theory is an explanatory myth for those who have lost their faith in official versions of everything, including reality. “When men stop believing in God, it isn’t that they then believe in nothing: they believe in everything,” says a character in Umberto Eco’s darkly funny send-up of conspiracy theory, Foucault’s Pendulum. “I want to believe,” the phrase on a UFO poster in Fox Muldur’s office, is one of The X-Files‘ shibboleths.

But even for those of us who don’t want to believe (or won’t admit that we do), conspiracy theory has become the horoscope of the late nineties, a kitschy charm against chaos, a novelty song to whistle in the gathering millennial gloom. It’s a manifestation of the postmodern zeitgeist, whose knowing sensibility is neatly summed up in the computer hacker’s expression “ha-ha-only-serious.”

By no coincidence, tongue-in-cheek conspiracy theories are classic examples of the ha-ha-only-serious sensibility. Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49 is a precursor, but the ur-text is undeniably the Illuminatus! trilogy, by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, a sprawling chronicle of the millennia-long power struggle between the anarcho-surrealist, chaos-worshipping Discordians and the evil, autocratic secret society known as the Illuminati. The Church of the SubGenius, an acid (in both senses) satire of fundamentalist Christianity and right-wing paranoia, is also a touchstone of ha-ha-only-seriousness. According to the church’s “lunatic prophecies for the coming weird times,” the SubGenii are the frontline in an apocalyptic battle against a global conspiracy of “Mediocretins, Assouls, Glorps, Conformers, Nuzis, Barbies, and Kens–FALSE PROPHETS and PINK BOYS who have made NORMALITY the NORM!”

Movies like Men in Black and Conspiracy Theory let us have our paranoia and mock it, too, as do books like The 60 Greatest Conspiracies of All Time (Jonathan Vankin and John Whalen), the Big Book of Conspiracies (Doug Moench), and It’s a Conspiracy: The Shocking Truth About America’s Favorite Conspiracy Theories (The National Insecurity Council).

The Schwa phenomenon plays to the postmodern mood as well. A brainchild of the graphic artist Bill Barker, Schwa is a somewhat inscrutable conceptual art project about “control, conspiracy, absurdity and despair,” disguised as a cottage-industry venture into GenX tchotchkes. (Or is it the other, way around? Trust no one!)Schwa’s black-and-white “alien defense products”–buttons, stickers, comic books, Alien Repellent Patches, Lost Time Detectors, and glow-in-the-dark T-shirts, most of them emblazoned with the archetypal almond-eyed alien head–use the paranoid folklore of alien invasion to lampoon millennial anxiety. “From alien detection to alien survival, there is now, for the first time, a complete line of actual objects you can own that will end your doubts about the unknown, right now, forever!” promises one Schwa pamphlet.

At the same time, Schwa’s red-alert warnings about the alien conspiracy, whose “subliminal coercion” and “bipolar marketing techniques” are washing the brains of those unknowing dupes the “Stickpeople,” is a cartoon critique of our ad-addled, TV-o.d.’d culture. “Media manipulation campaigns are crucial to the success of any Schwa world operation,” informs the Schwa World Operations Manual, a handbook for humans who’d like to try their hands at world domination. “Past experiences have helped us come up with a number of robust slogans which, if properly used as campaign kernels, will achieve the maximum amount of psychological pliability…. `Export Television Slavery’ and `TVs Are Needles’ are perfect illustrations of this approach.” Ironically, the Manual cites the early Schwa phenomenon itself (a “modest, small-scale and cryptic” effort involving “the heavy use of keychains and stickers”) as a textbook example of the covert penetration of the public mind. You may already be a Stickperson.

Craig Baldwin’s underground masterpiece, Tribulation 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (1991), also improvises on the intertwined themes of conspiracy theory and alien invasion in the ha-ha-only serious mode, though to a more pointedly political end. Baldwin’s film is a barrage of jump-cut imagery, snipped from Atom Age rocket operas and creature features and glued together with tense, hoarsely whispered narration. In a clench-jawed, Deep Throat voice, the narrator weaves virtually every major article of paranoid faith into the mother of all conspiracy theories.

Tribulation 99 is a tangled tale of alien invaders, Marxist revolutionaries, cattle mutilation, the Watergate break-in, and, of course, the assassination of JFK. True to the ha-ha-only serious spirit, Baldwin’s deadpan mockumentary crosses paranoid delusions with suppressed history, interweaving snippets of War of the Worlds and news footage of the American invasion of Grenada, the cracked belief in a hollow Earth and the cold facts of U.S. covert operations in Latin America.

“What came to a head [in Tribulation 99] was the whole Iran-Contra affair, Oliver North’s trial,” says Baldwin. “I wanted to make a statement that was critical of the CIA and our meddling in foreign countries, and it seemed to be a new [way to use] this creative material, these paranoiac rants.” He was struck by the unnerving way in which certain ideas hovered “between the official, political history and the very unofficial paranoiac version of things. There were often these weird alignments. Sometimes it was easier to believe the UFO stuff than it was to believe the CIA story that was used to justify our intervention in some country. So I lined them up, superimposed them…. I took real, political material and retrofitted it with the fantastic, wacko literature.”

Like Tribulation 99, The X-Files explores the borderland between suppressed fact and wacko fancy, between national nightmares and the bad dreams of solitary weirdos, be they lone gunmen or mutant contortionists who subsist on human livers. And like Baldwin’s movie, the series cloaks a deepening distrust of government in the pulp mythology of an alien conspiracy. The X-Files is about two lone-wolf FBI agents, Muldur and his female partner Dana Scully, who investigate cases involving paranormal phenomena, classified as “X” files: giant flukeworms, gender-morphing aliens, Satan-worshiping substitute teachers. It’s a thankless task, one that often earns the duo their boss’s ire, not to mention the wrath of the quintessential old boys’ network, the conspiratorial Syndicate–Well-Manicured Man, Fat Man, and Cigarette-Smoking Man, a.k.a. Cancer Man (who, it can now be revealed, was behind the assassinations of both Kennedys and Martin Luther King, Jr.). For these gray eminences, genetically engineering human-alien hybrids using techniques perfected by Nazi eugenicists and orchestrating a government cover-up of the whole nasty business is all in a few decade’s work.

The antigovernment sentiment that hangs menacingly over The X-Files first appeared on our mental horizons during Watergate (though it took Ronald Reagan’s covert policy of benign neglect toward a government he openly regarded as “not the solution but the problem” to whip this free-floating contempt into the angry thunderhead it is today). The X-Files is haunted by the restless ghosts of Watergate and Vietnam, with Richard Nixon, the patron saint of conspiratorial realpolitik and bunker paranoia, at their head. The Machiavellian stratagems of the Syndicate recall the ruthless maneuverings of the shifty-eyed president who forged an enduring link in the American mind between the White House and dark deeds: breakins, buggings, shoe boxes filled with money, and shady deals with Howard Hughes. The evil old white guys even look like Tricky Dick: As one writer noted, Syndicate members “all have a faintly jowly, Nixonian cast to them.” Deep Throat, the trench-coated Virgil who guides Muldur into the netherworld of alien cover-up, takes his name from the mysterious Watergate informant. Even the show’s Nazi themes have Nixonian echoes in the thinly veiled Naziphilia of G. Gordon Liddy, the Watergate burglar who named his dirty-tricks brigade ODESSA, after the underground association of former SS members, and who titled his memoirs Will (as in Triumph of the).

Chris Carter, the X-Files‘ creator, speaks for a generation when he says, “I’m 40. My moral universe was being shaped when Watergate happened. It blew my world out of the water. It infused my whole thinking.”

At the same time, the show strikes a sympathetic chord with its huge following (20 million and counting) because it plays on our millennial fears. The Syndicate’s ongoing attempt to create a human-alien master race, and episodes like “The Erlenmeyer Flask,” about a plot to spread an extraterrestrial virus via gene therapy, hint at uneasiness over genetic engineering at a time when eugenics is sexy again, rehabilitated by a new wave of genetic determinists after decades of disrepute. The conspirators’ use of alien implants to track their human guinea pigs, and the homicidal psychosis triggered by ATMs and cell phones in the episode “Blood,” give shape to the future shock that shadows the cyberhype of the nineties. That no one ever really dies on the show, that everyone is reincarnated or reanimated, is a symptom of the graying Baby Boom’s anxious premonitions of mortality. As well, episodes that have grim fun with forty-something hysteria about teenage anomie (“D. P. O.,” “Syzygy”) make light of the Boomers’ worst fear: that they’ve become their parents.

The X-Files tells electronic campfire stories about social upheaval, moral vertigo, and the breakneck pace of technological change at the end of the century. “I really think the world is spinning out of control,” says Carter. “There’s no work ethic anymore and no real moral code. I’m trying to find images to dramatize that.”

Sometimes, of course, we prefer our paranoia lite, as in The Truman Show (1998), a movie in which the New Age dream of pronoia comes nightmarishly true. Unbeknownst to Truman Burbank, his life is a TV show, a global obsession with its own line of merchandise and theme bars. His fishbowl world is surveilled by 5,000 miniature cameras and sealed inside a giant biodome. Everyone in his postcard-perfect, litter-free town of Seahaven, including his doting Stepfordian wife and his beer-swilling good buddy, is a paid actor. From a control booth concealed in the fake moon, the show’s godlike producer can cue the sun or cause a little rain to fall into Truman’s life.

In time, however, Truman begins to suspect that he’s at the heart of a benign conspiracy. Ultimately, he strikes, like Ahab, at the pasteboard mask of his fabricated reality (though with happier results). “How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall?” says Ahab. In unwitting fulfillment, Truman rams the nose of his boat through the painted wall of the biodome. Trying to dissuade him from leaving the Disneyesque utopia of a world where every smiling cast member is conspiring to help him, the omniscient producer offers an inside-out version of X-Files wisdom: “There’s no more truth out there than there is in the world I created for you.”

We cheer Truman on in his jailbreak from a place where he can Trust No One, into the Truth Out There–until we remember, with a slightly sinking feeling, that Out There is right here. What will become of the sweet naif, the boy in the TV bubble, in a world where it isn’t always morning in America and the corner newsie doesn’t greet him cheerily by name? For those who’ve seen their quality of life fray around the edges, unraveled by the slashing of public services and fears of violent crime, the notion of a benevolent conspiracy dedicated to ensuring that we always have a nice day holds a bittersweet appeal. The Disney executives who dreamed up the eerily Seahavenlike planned community of Celebration, in Orlando, Florida, know this well.

There’s a techno-logic to the popularity of paranoia in fin-de-millennium America. “This is the age of conspiracy,” says a character in Don DeLillo’s Running Dog, the age of “connections, links, secret relationships.” Like conspiracy theory, the Information Age is about hermetic languages, powerful cabals, maddeningly complex interconnections: software code, encrypted data, media mergers, global networks, neural nets.

In fact, conspiracy theory and the Information Age are joined at the hip: both sprang from the brow of the Enlightenment, whose unshakable faith in rationalism and materialism made technological modernity possible. The sleep of reason may breed monsters, but so does an excess of rationality: conspiracy theory’s fetishization of information and its Newtonian faith in a universe of clockwork causality are diseases of the Age of Reason.

In one of history’s more delicious ironies, those true sons of the Enlightenment, the Illuminati, are also the unwitting fathers of modern conspiracy theory. The Illuminati were a Masonic secret society formed in eighteenth-century Bavaria to further the Enlightenment goal of a rational, humanist society, freed from centuries of domination by crown and church. The group only lasted from 1776 until 1785, but by 1797, when the eminent Scottish scientist John Robison published Proofs of a Conspiracy Against All the Religions and Governments of Europe, carried on in the Secret Meetings of Free Masons, Illuminati, and Reading Societies, the Illuminati were fast becoming posthumous stars of paranoid fantasy. Two centuries later, they’re still close contenders, after international Jewry and the U.N., for the role of the dark architects of global domination–the secret schemers behind the French and Russian revolutions, the elders of Zion, and the rise of Hitler (!).

In their Dialectic of Enlightenment, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer argue that Enlightenment reason degenerated into the “instrumental reason” of the modern age, which uses technology to control people and nature in the name of capitalist profit. Following Adorno and Horkheimer’s logic, Enlightenment rationalism, taken to extremes, becomes the command-and-control mind-set of military-industrial technocracy, which in turn gives rise to the techno-paranoia of conspiracy theory: fears of surveillance via microchip implants, Satanic domination through universal product codes, U.N. invaders guided by stickers on highway signs. (Ironically, the wildfire spread of conspiracy theories and antigovernment networking would be impossible without Information Age innovations such as computer bulletin boards, desktop publishing, and shortwave radio broadcasting.)

Simultaneously, the computer interfaces whose metaphors are beginning to structure our worldview–the World Wide Web, Microsoft’s Windows–seem to confirm the paranoid assumption that everything is connected, that everything is a symbol, fraught with hidden meanings. Clicking through Windows’ infinite regress of menus and submenus or leaping from hyperlink to hyperlink across the Web, we enter the mind of Casaubon, one of the lunatic editors (who just might be CIA operatives) in Foucault’s Pendulum. “I was prepared to see symbols in every object I came upon,” he says. “Our brains grew accustomed to connecting, connecting, connecting everything with everything else.”

Also, there’s a weird parallelism between conspiracy theory and the academic vogues of the past few decades. Semiotics, which sees everything from Ted Koppel’s hair to superheroes as part of a cultural code to be cracked, is no stranger to the paranoid style. The pop semiotician Wilson Bryan Key made a career of conjuring up the specter of Madison Avenue mind control. His contribution to what McLuhan called “the folklore of industrial man,” the notion that “subliminal seductions” are lurking in every ad, lives on in the mind of every teenager who has ever performed the parlor trick of revealing, to amazed and amused friends, the word SEX written on the surface of a Ritz cracker, the naked woman hidden in the liquor-ad ice cubes, the man with the hard-on concealed in the foreleg of the camel on the front of a pack of regular, unfiltered Camels.

Along with semiotics, other conspiratorial academic trends include deconstruction, which teaches that meaning is a mercurial thing, impossible to pin down, and New Historicism, which argues that the notion of “objective” history, free from cultural biases, is a naive fiction, and that every historical account can therefore be read and dissected as literature. All three schools of critical thought conceive of the cultural landscape as a literary text, replete with hidden meanings. And all three veer perilously close to conspiracy theory when they willfully stretch or shave the text to fit Procrustean ideologies. At such moments, they meet their demented doppelganger, conspiracy theory, coming from the opposite direction.

Conversely, the best conspiracy theorists are unhinged scholars, virtuosos of overinterpretation and amok “intertextuality” (the lit-crit notion that every work is inextricably intertangled in a web of allusions to other texts). In his classic study, The Paranoid Style in American Politics, Richard Hofstadter argues that the paranoid mentality “believes that it is up against an enemy who is as infallibly rational as he is totally evil, and it seeks to match his imputed total competence with its own, leaving nothing unexplained and comprehending all of reality in one overreaching, consistent theory. It is nothing if not `scholarly’ in technique. [Senator Joseph] McCarthy’s 96-page pamphlet McCarthyism contains no less than 313 footnote references, and [Robert H. Welch, Jr.’s] fantastic assault on Eisenhower, The Politician, is weighed down by a hundred pages of bibliography and notes.”

Thus it is that Ron Rosenbaum, a connoisseur of crackpot hermeneutics, calls the obsessives who mine the Warren Commission Report for buried truths “the first deconstructionists.” He thrills to the flights of interpretive fancy of Kennedy assassination buffs like Penn Jones, conspiracy theorists “whose luxuriant and flourishing imaginations have produced a dark, phantasmagoric body of work that bears … resemblance to a Latin American novel (Penn is the Gabriel Garcia Lorca of Dealey Plaza, if you will).”

The 26-volume Warren Commission Report is the Finnegans Wake of paranoid America. Indeed, Don DeLillo, who traces our “deeply unsettled feeling about our grip on reality,” our disquieting sense of the “randomness and ambiguity and chaos” of things to “that one moment in Dallas,” has called the Warren Report the novel that James Joyce might have written if he had moved to Iowa City and lived to be a hundred. It is the Mount Everest of outsider exegesis, challenging virtuosos of conspiracy theory to ever greater heights of interpretive excess. The acknowledged masters of this underground art, like the reclusive octogenarian James Shelby Downard, have used the historical facts of the Kennedy assassination (such as they are) as a springboard for breathtaking leaps of logic and intertextual acrobatics.

A self-styled student of “the science of symbolism,” Downard beckons us to follow him through a maze of synchronicities that leads, by twists and turns, to a mind-warping conclusion: that official history is a blind for a monstrous conspiracy of Masonic alchemists hell-bent on the conquest of the collective id–the “control of the dreaming mind” of America. The Masons’ master plan involves three alchemical rites, one of which, an ancient fertility rite known as the killing of the king, was reenacted in the assassination of JFK.

In his essay “King-Kill/33: Masonic Symbolism in the Assassination of John F. Kennedy,” Downard plumbs the dark depths of Eros and Thanatos in the murder of JFK–”a veritable nightmare of symbol-complexes having to do with violence, perversion, conspiracy, death and degradation.” In a tour-de-force of surrealist explication, he dredges up connections between Jack Ruby, who was born Jacob Rubinstein, and a “jack ruby,” pawnbroker’s slang for a fake ruby, which somehow leads to the Ruby Slippers in The Wizard of Oz, the “immense power of `ruby light,’ otherwise known as the laser,” and the ruby’s symbolic associations with blood, suffering, and death.

Downard’s discursive, free-associated style defies synopsis, but a brief excerpt from his essay offers a taste of his inimitable voice:

Dealey Plaza breaks down symbolically in this manner: “Dea” means “goddess” in Latin and “Ley” can pertain to the law or rule in Spanish, or lines of preternatural geographical significance in the pre-Christian nature religions of the English. For many years, Dealey Plaza was underwater at different seasons, having been flooded by the Trinity River until the introduction of a flood-control system. To this trident-Neptune site came the “Queen of Love and Beauty” [Jackie Kennedy] and her spouse, the scapegoat in the Killing of the King rite, the “Ceannaideach” (Gaelic word for Kennedy meaning “ugly head” or “wounded head”).

For Downard, it all adds up: “Masonry does not believe in murdering a man in just any old way and in the JFK assassination it went to incredible lengths and took great risks in order to make this heinous act … correspond to the ancient fertility oblation of the Killing of the King.” Despite Downard’s dead seriousness about his subject, his writing betrays a Casaubonlike delight in spinning out far-flung connections, in pushing the interpretive envelope beyond the physical realities of entry wounds and bullet trajectories, into the metaphysical.

But conspiracy theory is more than lunatic hermeneutics, Information Age psychosis, a paranoid theology for a nation losing its religion, or a posttraumatic reaction to Watergate and Waco. It’s also a panic-attack reaction to everyday life in the age of Totally Hidden Video, where a little paranoia is admittedly in order. Again, DeLillo in Running Dog:

We’re all a little wary…. Go into a bank, you’re filmed…. Go into a department store, you’re filmed. Increasingly, we see this. Try on a dress in the changing room, someone’s watching you through a one-way glass. Not only customers, mind you. Employees are watched too, spied on with hidden cameras. Drive your car anywhere. Radar, computer traffic scans. They’re looking into the uterus, taking pictures. Everywhere. What circles the earth constantly? Spy satellites, weather balloons, U-2 aircraft. What are they doing? Taking pictures. Putting the whole world on film.

These days, surveillance cameras seem to peer, as in The Truman Show, from every nook and cranny in our public spaces, especially the high-tech workplace. Software monitors the keystroke speed, error rate, bathroom trips, and lunch breaks of data-entry clerks, telemarketers, and other postindustrial workers, enabling an Orwellian degree of oversight that would have gladdened the heart of Frederick Winslow Taylor, father of the “scientific management” of the modern workforce.

Computer networks have opened our credit histories and medical records to the prying eyes of employers, insurers, and direct-mail marketers. An e-mail ad for “Net Detective” software asks, “Did you know that with the Internet you can discover EVERYTHING you ever wanted to know about your EMPLOYEES, FRIENDS, RELATIVES, SPOUSE, NEIGHBORS, even your own BOSS!” On-line snoopers who pony up $22 will be able to “look up ‘unlisted’ phone numbers,” “check out your daughter’s new boyfriend!” and “find out how much alimony your neighbor is paying!”

Increasingly, though, we’re embracing our paranoia and learning to love the cam: “Spy shops” like New York City’s Spy World and Counter Spy Shop are proliferating in response to consumer demand for devices like the teddy bear with a tiny video camera concealed in one eye, just the thing for nervous parents who want to spy on their nannies.

Less laughably, a December 1997 report delivered to the European Commission confirmed the long-suspected existence of the ECHELON system, a global electronic surveillance network operated by the U.S.’s shadowy National Security Agency that “routinely and indiscriminately” eavesdrops on e-mail, fax, and even phone communications around the world, using artificial-intelligence programs to search for key words of interest. And while the government may not be secretly implanting microchip tracking devices in our buttocks, as Timothy McVeigh believed, tough-on-crime types like Senator Dianne Feinstein are clamoring for a mandatory national I.D. card with an electronic fingerprint or voiceprint. Privacy Journal publisher Robert Ellis Smith thinks biometric federal I.D. cards would be a grave threat to civil liberties, a step down the slippery slope to the government implants of McVeigh’s fever dreams. Not that there isn’t ample cause for concern right now: In recent years, the FBI has reportedly spent $2 billion annually to assemble a databank of genetic information about American citizens.

The revelation that the government is reading our e-mail, eavesdropping on our conversations, spying on us from earth orbit, and archiving our genetic data casts a somewhat charitable light on conspiracy theory. So does the by now universal realization that the government does, in fact, flagrantly flout the will of the people, trample the law, and attempt to cover up its skullduggery. From COINTELPRO to Iran-contra, the bizarre capers of the postwar decades are stranger than paranoid fiction: Who could make up CIA operations like MK-ULTRA, a covert $25 million-dollar mind-control experiment in which unwitting human guinea pigs (one of whom later committed suicide) were dosed with LSD? Or the agency’s $21 million-dollar program to harness the surveillance powers of “remote viewing,” the supposed psychic ability to see distant or hidden objects with the mind’s eye?

At least the millions in tax dollars the CIA flushed down the toilet for its Keystone Kops-meet-the-Psychic Friends Hotline scheme buy a few pained guffaws. But the laughter curdles when grimmer truths come to light, like the U.S. Energy Department’s Cold War experiments in which 16,000 people, including infants and pregnant women, were exposed to radiation, or the 1950 germ warfare experiment in which a Navy minesweeper sprayed San Francisco with rare Serratia bacteria, sending 11 unknowing victims to the hospital and one to the cemetery.

As we numbly skim the list of atrocities our government has perpetrated on its own citizens, often with corporate America as a cozy co-conspirator, Sven Birkerts’s defense of paranoia comes to mind: “Paranoia is a logical response to a true understanding of power and its diverse pathologies.” A literary critic who came of age in the sixties, Birkerts defines paranoia as “what happened when the illusions of the counterculture collapsed and the true extent of the political web became apparent.” To him, the “paranoid” worldview is the political equivalent of X-ray specs, revealing what passes for public discourse in our infotainment age to be mere “distraction, spectacle, and the bromides of public relations.” It rips away the tabloid sideshow banners of our TV culture to expose the stark reality of a democracy in crisis, “the deeper exchanges of our body politic controlled by the machinations of an elite.”

Birkerts is fond of the countercultural maxim that paranoia is just “a heightened state of awareness.” Indeed, the worst thing about some of the late-night paranoid musings known as conspiracy theories is that they’re true. America really does use its imperial power to prop up repressive regimes that are sympathetic to U.S. foreign policy and business interests, and to subvert democratically elected governments that aren’t. According to David Burnham, a reporter who specializes in law-enforcement issues, the FBI (“the most powerful and secretive agency in the United States today”) really is an Orwellian spook house whose routine conduct–indulging its surveillance fetish with databases of information about millions of law-abiding citizens while turning a blind eye on civil rights abuses and corporate crime–is incompatible “with the principles or practices of representative democracy.” And, as Birkerts suspects, the corporate newsmedia really are instruments of social control, galvanizing public opinion in support of elite agendas.

Of course, in the been-there, done-that, media-savvy nineties, none dare call it conspiracy; better, perhaps, to borrow the fashionable lingo of chaos theory. For example, the media’s propagandistic function might be described as an “emergent phenomenon,” a pattern that comes into being not as a result of deep-laid plans by a nefarious cabal but through the complex interaction of elements in a turbulent system. These elements include the increasingly concentrated ownership and bottom-line orientation of the dominant media outlets; the censorship exercised by the mass media’s primary income source, their advertisers; and the media’s reliance on pre-spun information provided by government and business sources and prefab “experts” selected and supported by vested interests. As Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argue in Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, these factors “interact with and reinforce one another,” filtering out systemic critiques of free-market economics, multinational capitalism, and American foreign policy and leaving only the news that’s “fit to print.”

Herman and Chomsky aren’t lone gunmen. Media critics like Ben Bagdikian and Herbert Schiller and organizations like Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting and Project Censored have excavated mountains of evidence of the corporate newsmedia’s instrumental role in mustering mass support for “the economic, social, and political agenda of privileged groups that dominate the domestic society and the state,” as Herman and Chomsky put it. For those who dismiss such charges as Chicken Little leftism, consider the following:

* In 1985, the public-television station WNET lost its corporate funding from Gulf + Western after it showed the documentary Hungry for Profit, which critiqued multinational corporate activities in the Third World. Despite one source’s flabbergasting claim that station officials did all they could to “get the program sanitized,” Gulf + Western was much vexed, and withdrew its funding. One of the company’s chief executives complained to the station that the show was “virulently anti-business if not anti-American.” The Economist drily noted, “Most people believe that WNET would not make the same mistake again.”

* In 1989, a federal investigation revealed that as many as 60 percent of the bolts American manufacturers used in airplanes, bridges, and nuclear missile silos might be defective. A report scheduled to be aired on NBC’s Today show noted that “General Electric engineers discovered they had a big problem. One out of three bolts from one of their major suppliers was bad. Even more alarming, GE accepted the bad bolts without any certification of compliance for eight years.” The unflattering reference to GE was removed from the story before it aired. By curious coincidence, GE also happens to own NBC.

* In 1990, images of an overwrought young Kuwaiti woman testifying before the Congressional Human Rights Caucus mesmerized American TV viewers. Identified as an anonymous “hospital volunteer” (her identity had to be kept secret to ensure her safety, we were told), the girl tearfully recounted a shocking tale of premature babies torn from their incubators and left to die on the cold hospital floor by soldiers in the Iraqi forces that invaded Kuwait. Her testimony was instrumental in mobilizing public support for Operation Desert Storm. After the war was over, the girl was revealed to be the daughter of the Kuwaiti ambassador. Her whereabouts during the purported events have never been verified, and her horror story remains unsubstantiated to this day. What is certain, however, is that the Caucus meeting was orchestrated by the elite public-relations firm Hill and Knowlton, which helpfully provided the witnesses who testified. The Kuwaiti family in exile had hired Hill and Knowlton to muster public support for U.S. military intervention.

Institutional critiques buttressed by examples of deep, systemic flaws such as these stand in stark contrast to the morality plays favored by mainstream commentators, in which “bad apples” like Richard Nixon or Michael Milken or Mark Fuhrman are scapegoated while the system that produced them goes unchallenged–an analysis that actually serves to reaffirm the essential soundness of the status quo. Herman and Chomsky anticipate the knee-jerk response to such indictments. “Institutional critiques,” they write,

are commonly dismissed by establishment commentators as `conspiracy theories,’ but this is merely an evasion…. In fact, our treatment is much closer to a `free market’ analysis, with the results largely an outcome of the workings of market forces. Most biased choices in the media arise from the preselection of right-thinking people, internalized preconceptions, and the adaptation of personnel to the constraints of ownership, organization, market, and political power.

In other words, no one’s in charge; in the late twentieth century, the real conspiracies have many tentacles but no heads.

Thus, as evidence mounts of covert government operations, corporate surveillance, and the propagandistic function of the media, it’s becoming increasingly clear that some conspiracy theories are true lies.

On the other hand, sometimes a paranoiac is only a paranoiac. Judging from recent events, a startling number of Americans have crossed over, into the paranoid parallel world of The X-Files. They “know” that the rumor-shrouded suicide of the White House deputy counsel Vince Foster was actually the murder of a Man Who Knew Too Much, authorized at the highest level. They “know” that TWA Flight 800 was accidentally blown out of the sky by “friendly fire” from a U.S. Navy cruiser (if it wasn’t zapped by unfriendly aliens, that is). They “know” that Area 51, an ultrasecret military base hidden away in the Nevada desert, is more than a proving ground for black-budget spycraft like the delta-shaped Aurora, the diamond-shaped “Pumpkin Seed,” and the usual complement of Nightstalkers, Goatsuckers, and Grim Reapers (more prosaically known as stealth fighters). According to the true believers in David Darlington’s Area 51, it’s also the birthplace of the AIDS virus, the resting place of the Roswell aliens, and the final destination of all those missing kids on milk cartons, who end up as the subjects of unspeakable experiments conducted in the base’s underground labs. Rumors abound, writes Darling, that Area 51 is overseen “not by such earthbound lackeys as Congress or the President or even the Air Force, but by the Bilderbergs/Council on Foreign Relations/Trilateral Commission/One World Government/New World Order–different names for the clandestine cabal operating within/outside the military-industrial complex. These renegade powermongers [will] stop at nothing to achieve their aim, which [is] no less sinister or ambitious a goal than worldwide domination.”

To the worldly-wise, such beliefs have a campy appeal; they sound like the political equivalent of the B-movie classic, The Incredibly Strange Creatures Who Stopped Living and Became Mixed-Up Zombies. But the joke sours when we realize that what Hofstadter famously called “the paranoid style in American politics”–the Manichean belief that a sinister yet subtle conspiracy is waging covert war on the American Way of Life–is back with a bang, and its devotees are deadly serious.

Unmarked black helicopters, ominous portents of the U.N.’s imminent invasion of the American heartland, darken the mental skies of the estimated 10,000 to 40,000 Americans in the right-wing antigovernment militia movement. Their sympathizers may number in the hundreds of thousands. The hate-group expert Kenneth S. Stern calls the militia movement the “fastest-growing grassroots mass movement” in recent memory.

In these times, a man like Timothy McVeigh–”a very normal, good American serving his country,” in the words of his Army roommate–can morph into a paranoid antigovernment extremist who believes the Army has implanted a microchip in his buttocks to track his whereabouts. In the eerie night-vision world of The Spotlight, Patriot Report, and the other far-right periodicals that McVeigh devoured, Mongolian hordes are massing in the mountains; members of the infamous Crips and Bloods gangs are being trained as shock troops for the invasion; Russian forces are waiting for zero hour in salt mines under Detroit; and the Amtrak repair yards in Indianapolis are slated for conversion into an enormous crematorium, the final solution for all who resist the New World Order. Some even claim that the conspiracy is hiding its plan for dividing up the land of the (formerly) free in plain sight, in a map on the back of a kid’s cereal box.

McVeigh’s pillow books included Operation Vampire Killer 2000 by the former Phoenix police sergeant Jack McLamb, a call to arms to police and military personnel to mobilize against the “elitist covert operation” whose stated goal is a “`utopian’ Socialist society” and “the termination of the American way of life” by–when else?–the year 2000. According to McLamb, the shadowy wire pullers behind the coming one-world government include international bankers, the Illuminati, the “Rothschild Dynasty,” Communists, the IRS, CBS News (!), the Yale secret society Skull and Bones, “humanist wackos,” space aliens, and, of course, the U.N.

McVeigh’s conspiracy theories read like an X-Files script written by Thomas Pynchon. They would be comic relief if they hadn’t ended in apocalypse: the explosion of a truck filled with 4,000 pounds of ammonium nitrate fertilizer near the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, on April 19, 1995, killing 168 innocent people. “Today, the far right is more active than ever, with subversive attacks being planned all across the country,” writes the militia watcher James Ridgeway. A correspondent for the far-right magazine The Spotlight claims to have received a spooky, unsigned postcard postmarked Oklahoma City, April 17. Blank on the back, its only message is the image on front, an ominous, Depression-era photo of a twister churning across the Dustbowl. The caption reads, “Dust storm approaching at 60 mi. per hr.” Kerry Noble, an antigovernment extremist convicted in a 1983 plot to blow up the Murrah building as a “declaration of war” against the U.S. government, speculates that the postcard’s cryptic message might be that “things were set in motion” by the Oklahoma bombing. “There’s another dust storm coming across,” he says.

(Continues…)

Copyright ” 1999 by Mark Dery. Reprinted with permission from Grove Atlantic, Inc. All rights reserved.