News Room

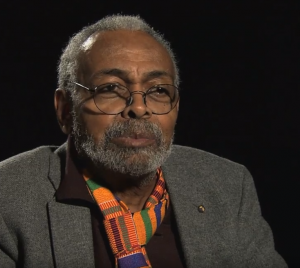

Today would have been the eighty-fourth birthday of Amiri Baraka — legendary poet, playwright, critic, activist, and troublemaker of radical distinction, from whose fifty-plus years of writing we assembled S O S: Poems 1961—2013 in 2016.

Today would have been the eighty-fourth birthday of Amiri Baraka — legendary poet, playwright, critic, activist, and troublemaker of radical distinction, from whose fifty-plus years of writing we assembled S O S: Poems 1961—2013 in 2016.

Amiri Baraka was born Everett Leroy Jones in Newark in 1934, and, following a dishonorable discharge from the Air Force in 1954, began writing under the name LeRoi Jones. After appearing in Donald Allen’s groundbreaking anthology The New American Poetry 1945—1960, which we published in 1960 (and re-released in an updated edition in 1982), he burst forth in 1961 with his first poetry collection, Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note. Poet and academic Anna Vitale has noted that the arresting book “brings to light something remarkable about suicidal fantasy: it can be one way to imagine a future, an outside, an immeasurably necessary potential.” In fact, “immeasurably necessary potential” might be one of the key forces guiding Baraka’s entire career.

Poet and scholar Kristen Gallagher has also written about the book, calling its style “uncertain… sometimes abstract lyric, sometimes visceral and incoherent, parodic in one poem, sincere in another. There’s anger, but its object remains unclear. The issue of race lurks, yet feels mostly repressed.”

In a statement on his own poetics from this time, the poet defiantly writes, “I CAN BE ANYTHING I CAN. I make a poetry with what I feel is useful & can be saved out of all the garbage of our lives. What I see, am touched by (CAN HEAR) … wives, gardens, jobs, cement yards where cats pee, all my interminable artifacts … ALL are a poetry, & nothing moves (with any grace) pried apart from these things.”

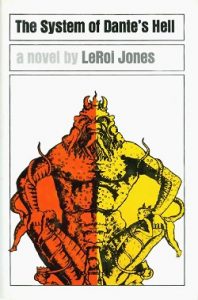

More books followed. In 1963, he published Blues People, a study of black music in America, beginning with the “weird and unbelievably cruel destiny” of the first enslaved Africans brought to this country. In 1964, his first play, Dutchman, set off a firestorm, winning an Obie award and igniting a heated political debate with fellow Newarker Philip Roth in the pages of the New York Review of Books. In 1965, we published his first novel, The System of Dante’s Hell, which Nick Tosches, in his book The Devil and Sonny Liston, calls “one of the most powerful and beautiful expressions of blind hatred and its wages since the Pentateuch.”

More books followed. In 1963, he published Blues People, a study of black music in America, beginning with the “weird and unbelievably cruel destiny” of the first enslaved Africans brought to this country. In 1964, his first play, Dutchman, set off a firestorm, winning an Obie award and igniting a heated political debate with fellow Newarker Philip Roth in the pages of the New York Review of Books. In 1965, we published his first novel, The System of Dante’s Hell, which Nick Tosches, in his book The Devil and Sonny Liston, calls “one of the most powerful and beautiful expressions of blind hatred and its wages since the Pentateuch.”

That same year, after the assassination of Malcolm X, LeRoi Jones made some major changes: he abandoned the life he had cultivated in the predominantly white avant-garde milieu of Greenwich Village, moved to Harlem, and founded the Black Arts Repertory Theater School. When the school failed after less than a year, he returned to Newark—the native city he referred to, like its founders, as “New Ark”—and created Spirit House, “a site for poetry readings, a theater, a place to hold discussions formal and otherwise and a general gathering site.” He soon adopted a new, Muslim name, Ameer Barakat, which pan-Africanist leader Ron Karenga would adjust to Amiri Baraka (from the Arabic-derived Swahili for “prince” and “blessing”). All of the changes in Baraka’s life and developments in his thinking were registered, with profound, visceral urgency, in his poetry.

In 1967—the same year Time magazine called Baraka “the snarling laureate of Negro revolt”—Newark combusted into scorching urban disquiet. In the events of that summer, Baraka was arrested on charges of possessing illegal firearms. At his trial, beholding a row of white potential jurors, he shouted, “They’re not my peers, they’re my oppressors!” Prosecutors would later read Baraka’s poem Black People into evidence, prompting Jimmy Breslin to quip that “LeRoi Jones got the toughest sentence to come out of the Newark riots because he writes lousy poetry.”

His politics experienced one more sea change in 1974, when, dissatisfied with black nationalism, he publicly embraced the Communist outlook he would profess for the rest of his life. As he explained in an interview with Maya Angelou in 1993, “I think it shapes my art in the sense that I am trying to get to the material base of whatever is going on — whatever I am describing, whatever event or circumstance or phenomenon I am trying to illuminate. I’m always looking for a concrete time and place and condition. I want to know why things are the way they are and how they became that way.”

His politics experienced one more sea change in 1974, when, dissatisfied with black nationalism, he publicly embraced the Communist outlook he would profess for the rest of his life. As he explained in an interview with Maya Angelou in 1993, “I think it shapes my art in the sense that I am trying to get to the material base of whatever is going on — whatever I am describing, whatever event or circumstance or phenomenon I am trying to illuminate. I’m always looking for a concrete time and place and condition. I want to know why things are the way they are and how they became that way.”

Amiri Baraka would remain ferocious, dedicated to his community, and tremendously productive, right up until his death in 2014 at the age of seventy-nine. He would publish, all told, more than ten collections of poetry, ten plays, and twelve works of nonfiction. In 1998, he became known to a younger generation, unversed in the public controversies of the sixties and seventies, when he appeared in Warren Beatty’s Bulworth. In 2002, he was named poet laureate of the State of New Jersey. Today, the mayor of New Ark is Ras J. Baraka, Amiri Baraka’s son.

In his 2014 obituary for the New Yorker, Jelani Cobb writes, “Baraka was foundational for a generation of writers who emerged in his wake, a singular figure whose work laid down the terms of engagement for many, if not most, of us who came to the craft after him. In his poems, plays, essays, criticism, and fiction, he achieved an absolute democracy of language — a poetry forged in the crucible of a collective experience, a musical fusion of history, irony, and art.”

S O S collects Baraka’s poetry from all the books of his fifty-plus-year career, tracking the changes in his commitments, affiliations, and interests, while simultaneously demonstrating the commitment to justice, community, and political imagination at the unified core of his writing. In the New York Times Book Review, Claudia Rankine called it “the most complete representation of over a half-century of revolutionary and breathtaking work.”

S O S collects Baraka’s poetry from all the books of his fifty-plus-year career, tracking the changes in his commitments, affiliations, and interests, while simultaneously demonstrating the commitment to justice, community, and political imagination at the unified core of his writing. In the New York Times Book Review, Claudia Rankine called it “the most complete representation of over a half-century of revolutionary and breathtaking work.”

Like all revolutionary art, Baraka’s poems can be jarring. But, as he himself wrote in a late poem to his wife, included in the collection:

What beauty is not anomalous

And strange, what love is not

In danger and fragile, what goodness

Is not sometimey and sweet, what grand

Joyousness not shy and seeming incomplete