News Room

On April 17th, Grove Atlantic will publish the thirtieth anniversary edition of Charles Kaiser’s 1968 in America: Music, Politics, Chaos, Counterculture, and the Shaping of a Generation, a book that is today widely recognized as one of the best historic accounts of the 1960s and which Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. called “A splendidly evocative account of a historic year—a year of tumult, of trauma, and of tragedy.”

Largely based on unpublished interviews and documents (including in-depth conversations with anti-war presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy and Bob Dylan), this is compulsively readable popular history. Now, fifty years later, and with a new introduction by Hendrik Hertzberg, it is even more clear that this was a uniquely terrible, wonderful, and pivotal year in the story of America.

Read an excerpt from Hendrik Hertzberg’s introduction in the Guardian: https://goo.gl/Xoo5pk

Here we present an excerpt from the edition’s brand-new epilogue, written by Kaiser in late 2017.

_________________________________________

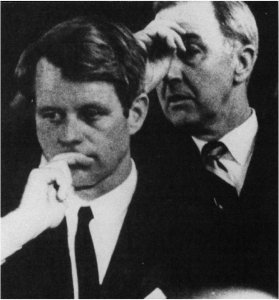

One of the only photographs of McCarthy and Kennedy together in 1968, inside the Ebenezer Baptist Church during King’s funeral.

Once a year, on the fourth of April, a few hundred people gather together at the corner of North 17th Street and East Broadway in Indianapolis, Indiana. They go there to commemorate the words Robert F. Kennedy spoke at that street corner on April 4, 1968—words so powerful, they kept their city peaceful while a hundred and thirty others would burst into flame. Bobby Kennedy was on his way to Indianapolis when word reached him that Martin Luther King, Jr. had been shot. Minutes before his plane landed, Kennedy learned that King had succumbed to his wound. Despite the warnings of the city’s mayor, Richard Lugar, who feared a riot, Kennedy drove straight to his scheduled campaign rally, in the heart of black Indianapolis. He was more than an hour late. Just before he arrived, the first rumor spread through the crowd, some twenty-five hundred strong: King had been shot, but he was alive.

A moment before he began, Kennedy can be heard asking his staff, “Do they know about Martin Luther King?” Most of the crowd did not yet know that King had died.

The civil rights hero and future Congressman John Lewis, who had been working for Kennedy in the Indiana primary, has said, “That evening Robert Kennedy spoke from his soul.” His speech was simple and elegant and beautiful. It may have been the best speech any Kennedy ever gave; it was certainly one of the most remarkable speeches any American has ever given. It would also be his first public mention of his brother’s assassination five years before. He began this way:

Ladies and gentlemen. I’m only going to talk to you just for a minute or so this evening because I have some very sad news for all of you. Could you lower those signs please? I have some very sad news for all of you, and I think sad news for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight in Memphis, Tennessee.

The crowd shrieked. Then it fell completely silent. Kennedy went on:

Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice between fellow human beings. He died in the cause of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black—considering the evidence evidently is that there were white people who were responsible, you can be filled with bitterness, and with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in greater polarization—black people amongst blacks, and white amongst whites, filled with hatred toward one another.

Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.

For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I would only say that I can also feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed. But he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to get beyond or go beyond these rather difficult times.

My favorite poem, my favorite poet was Aeschylus. And he once wrote: “Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.” What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness; but is love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black. [First applause.]

So I ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King–yeah, it’s true. But more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love. A prayer for understanding, and that compassion of which I spoke.

We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times. We’ve had difficult times in the past; and we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence, it is not the end of lawlessness, and it’s not the end of disorder.

But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings that abide in our land. [Cheers.] And dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world. Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people. Thank you very much.

The speech lasted less than six minutes.

Two months and one day later, another assassin murdered Robert Kennedy. Not every American lamented his death. But scores of millions did, including thousands of Democrats who had fought him in the presidential primaries—and now mourned him with as much pain as anyone.

As his funeral train moved slowly to his burial ground, like Lincoln’s a century before, the tracks were lined with silent, solemn, often weeping mourners. And for a moment, savageness was nearly tamed, and life was made gentle.